Archaeologists just mapped a Bronze Age megafortress in Georgia

A sprawling 3,500-year-old fortress offers tantalizing clues about a culture that once dotted the southern Caucasus mountains with similar walled communities.

Archaeologists recently used a drone to map a sprawling 3,500-year-old fortress in the Caucasus Mountains of southern Georgia. The detailed aerial map offers some tantalizing clues about the ancient culture whose people built hundreds of similar fortresses in a mountainous region that spans the modern countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. Based on their survey and excavations within the fortress walls, Cranfield University archaeologist Nathaniel Erb-Satullo and his colleagues suggest the fortified community may have been a place where nomadic herders converged during their yearly migration, but the evidence still leaves more questions than answers.

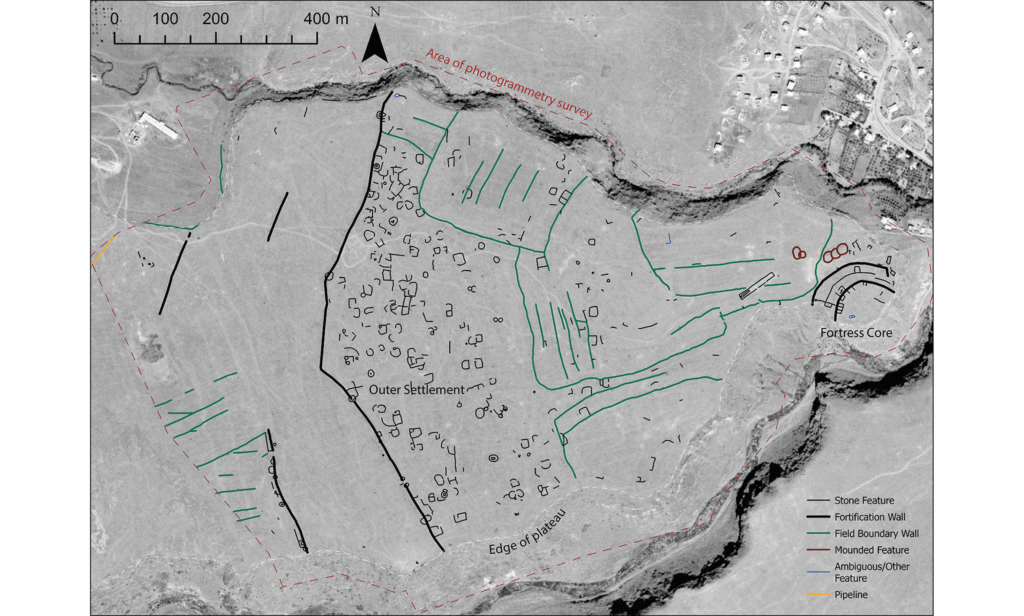

This map shows an aerial map of the ancient megafortress at Dmanisis Gora.

Credit:

Erb-Satullo et al. 2025

This map shows an aerial map of the ancient megafortress at Dmanisis Gora.

Credit:

Erb-Satullo et al. 2025

An abandoned ancient megafortress

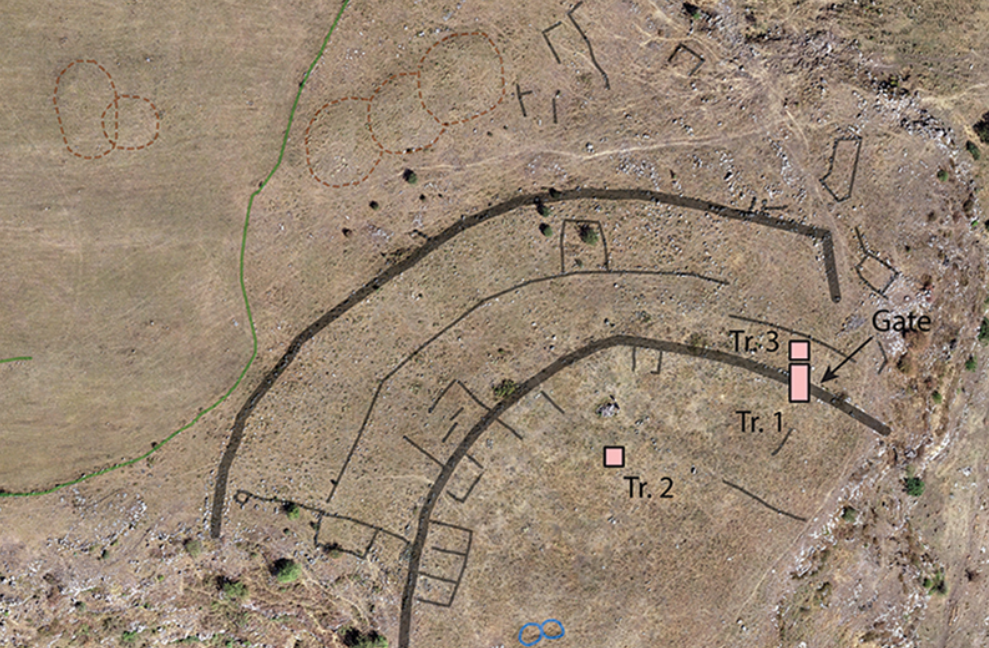

The half-buried Bronze Age ruins of Dmanisis Gora perch on a windswept promontory a few kilometers away from a cave where Homo erectus (or a close relative) lived 1.8 million years ago. Deep, steep-sided gorges run along two sides of the promontory, and sometime between 1500 and 1000 BCE, people stacked boulders into a double layer of high, thick walls to block off the end of the plateau from the plains to the west. Sheltered between the 4-meter high, 2.5-meter wide walls and the 60-meter-deep gorges, people built dugout houses, then later aboveground stone ones, along with stone animal pens and other buildings.

© Erb-Satullo et al. 2025