Drew Goddard on How ‘High Potential’ Brought Him Back to Broadcast, Adapting ‘Holes’ for TV and Why He’ll ‘Never Say Never’ About a ‘Lost’ Reboot (EXCLUSIVE)

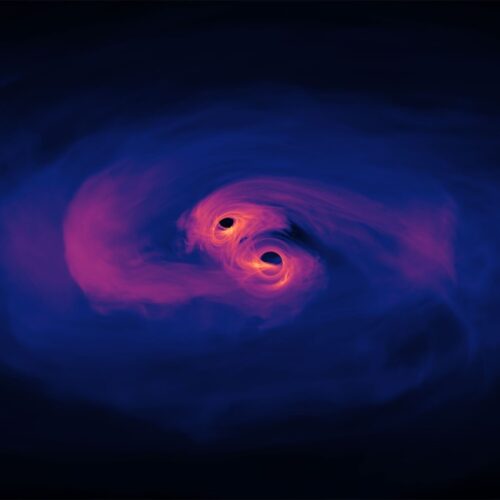

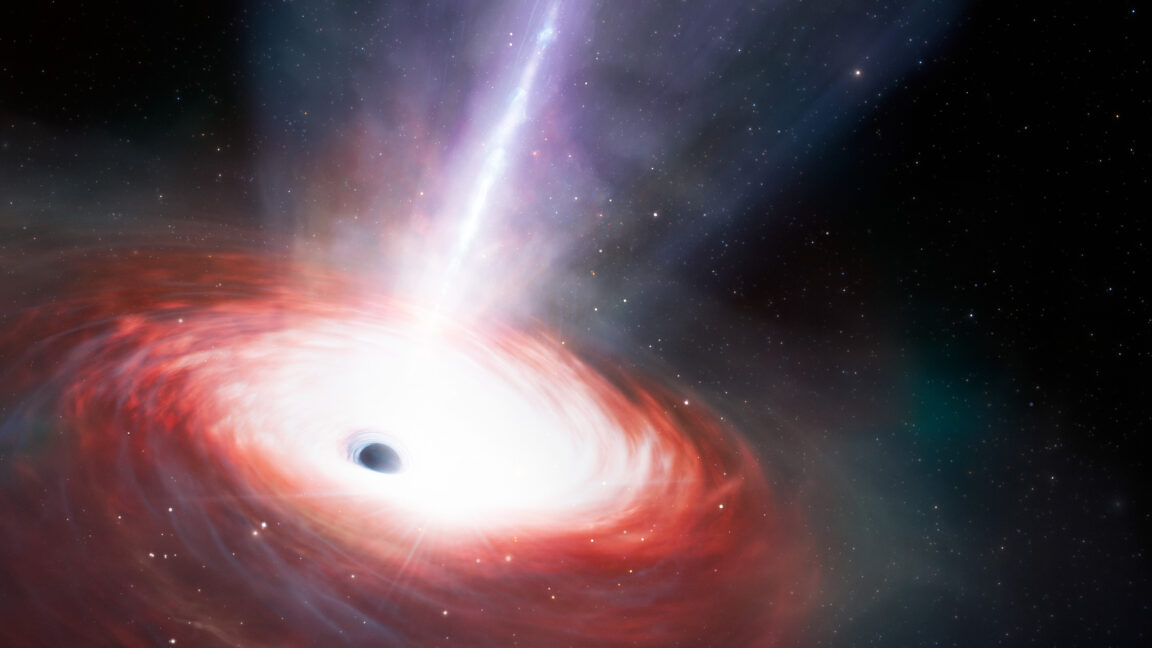

What happens when a gargantuan cloud of gas swallows a pair of monster black holes with their own appetites? Feasting on the gas can cause some weird (heavenly) bodily functions.

AT 2021hdr is a binary supermassive black hole (BSMBH) system in the center of a galaxy 1 billion light-years away, in the Cygnus constellation. In 2021, researchers observing it using NASA’s Zwicky Transient Facility saw strange outbursts that were flagged by the ALerCE (Automatic Learning for the Rapid Classification of Events) team.

This active galactic nucleus (AGN) flared so brightly that AT 2021hdr was almost mistaken for a supernova. Repeating flares soon ruled that out. When the researchers questioned whether they might be looking at a tidal disruption event—a star being torn to shreds by the black holes—something was still not making sense. They then compared observations they made in 2022 using NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory to simulations of something else they suspected: a tidal disruption of a gas cloud by binary supermassive black holes. It seemed they had found the most likely answer.

© Northwestern University

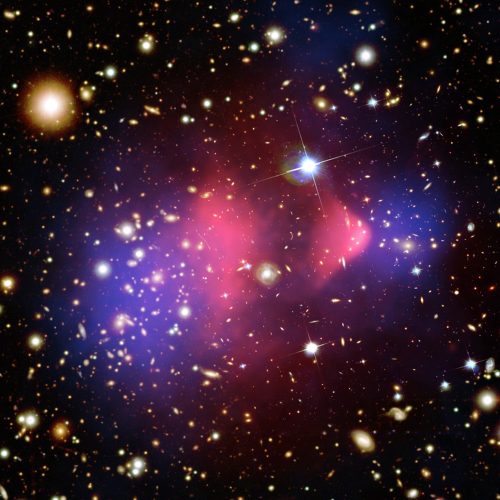

Emergent gravity is a bold idea.

It claims that the force of gravity is a mere illusion, more akin to friction or heat—a property that emerges from some deeper physical interaction. This emergent gravity idea might hold the key to rewriting one of the fundamental forces of nature—and it could explain the mysterious nature of dark matter.

But in the years since its original proposal, it has not held up well to either experiment or further theoretical inquiry. Emergent gravity may not be a right answer. But it is a clever one, and it's still worth considering, as it may hold the seeds of a greater understanding.

© APOD

How did supermassive black holes end up at the center of every galaxy? A while back, it wasn't that hard to explain: That's where the highest concentration of matter is, and the black holes had billions of years to feed on it. But as we've looked ever deeper into the Universe's history, we keep finding supermassive black holes, which shortens the timeline for their formation. Rather than making a leisurely meal of nearby matter, these black holes have gorged themselves in a feeding frenzy.

With the advent of the Webb Space Telescope, the problem has pushed up against theoretical limits. The matter falling into a black hole generates radiation, with faster feeding meaning more radiation. And that radiation can drive off nearby matter, choking off the black hole's food supply. That sets a limit on how fast black holes can grow unless matter is somehow fed directly into them. The Webb was used to identify early supermassive black holes that needed to have been pushing against the limit for their entire existence.

But the Webb may have just identified a solution to the dilemma as well. It has spotted a black hole that appears to have been feeding at 40 times the theoretical limit for millions of years, allowing growth at a pace sufficient to build a supermassive black hole.

© NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva/M. Zamani

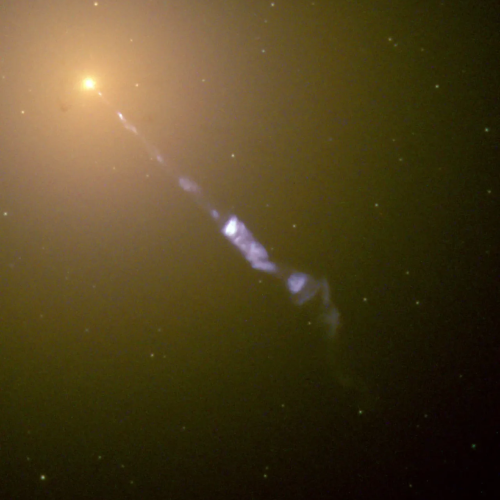

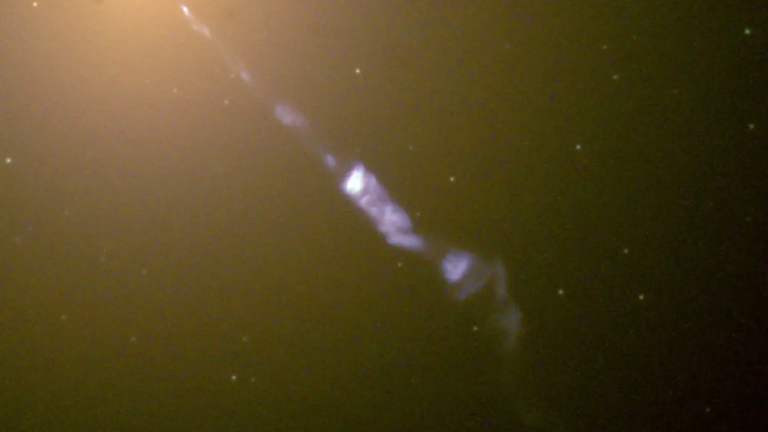

The intense electromagnetic environment near a black hole can accelerate particles to a large fraction of the speed of light and sends the speeding particles along jets that extend from each of the object's poles. In the case of the supermassive black holes found in the center of galaxies, these jets are truly colossal, blasting material not just out of the galaxy, but possibly out of the galaxy's entire neighborhood.

But this week, scientists have described how the jets may be doing some strange things inside of a galaxy, as well. A study of the galaxy M87 showed that nova explosions appear to be occurring at an unusual high frequency in the neighborhood of one of the jets from the galaxy's central black hole. But there's absolutely no mechanism to explain why this might happen, and there's no sign that it's happening at the jet that's traveling in the opposite direction.

Whether this effect is real, and whether we can come up with an explanation for it, may take some further observations.

© [CDATA[NASA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)]]

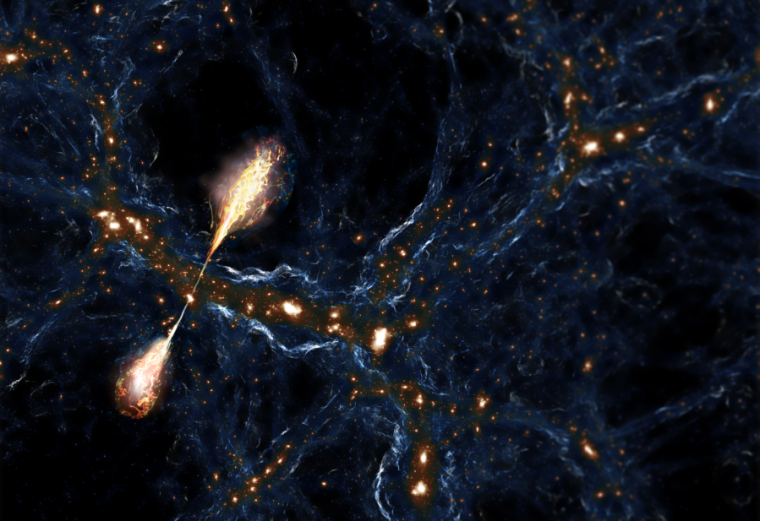

Enlarge / Artist's conception of a dark matter filament containing a galaxy with large jets. (Caltech noted that some details of this image were created using AI.) (credit: Martijn Oei (Caltech) / Dylan Nelson (IllustrisTNG Collaboration).)

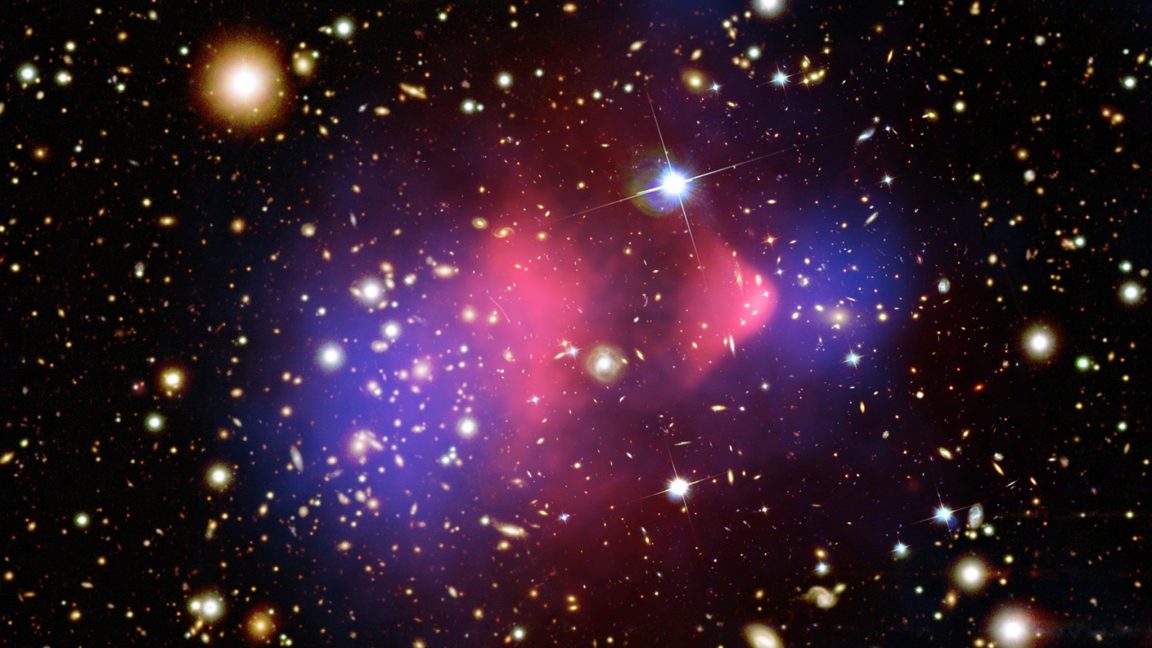

The supermassive black holes that sit at the center of galaxies aren't just decorative. The intense radiation they emit when feeding helps drive away gas and dust that would otherwise form stars, providing feedback that limits the growth of the galaxy. But their influence may extend beyond the galaxy they inhabit. Many black holes produce jets and, in the case of supermassive versions, these jets can eject material entirely out of the galaxy.

Now, researchers are getting a clearer picture of just how far outside of the galaxy their influence can reach. A new study describes the largest-ever jets observed, extending across a total distance of 23 million light-years (seven megaparsecs). At those distances, the jets could easily send material into other galaxies and across the cosmic web of dark matter that structures the Universe.

Jets are formed in the complex environment near a black hole. The intense heating of infalling material ionizes and heats it, creating electromagnetic fields that act as a natural particle accelerator. This creates jets of particles that travel at a substantial fraction of the speed of light. These will ultimately slam into nearby material, creating shockwaves that heat and accelerate that, too. Over time, this leads to large-scale, coordinated outflows of material, with the scale of the jet being proportional to a combination of the size of the black hole and the amount of material it is feeding on.

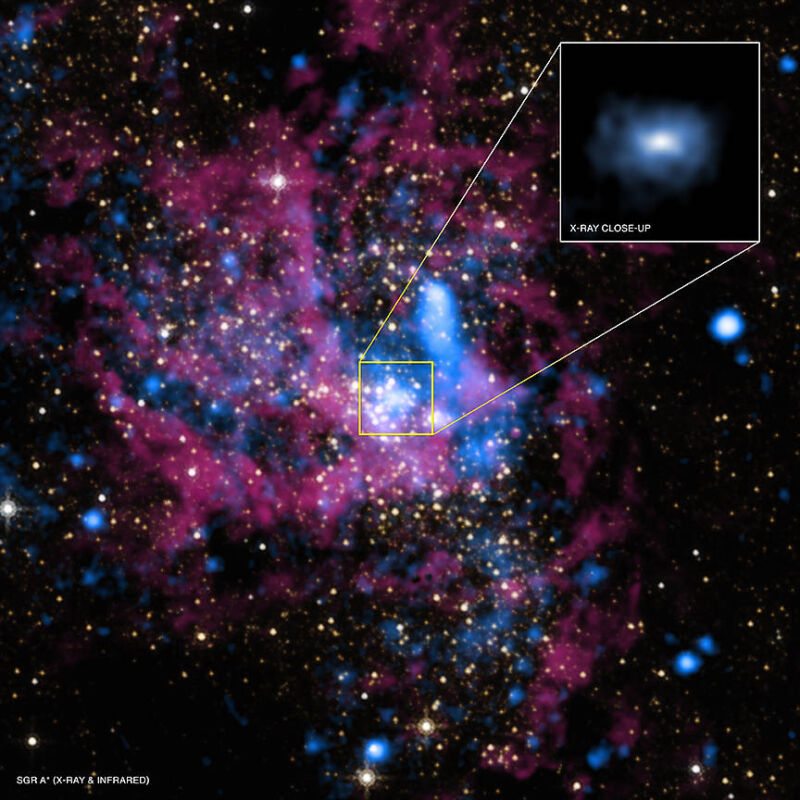

Enlarge / The Milky Way's central black hole is in a very crowded neighborhood. (credit: UMass/D.Wang/NASA/STScI)

Supermassive black holes are ravenous. Clumps of dust and gas are prone to being disrupted by the turbulence and radiation when they are pulled too close. So why are some of them orbiting on the edge of the Milky Way’s own supermassive monster, Sgr A*? Maybe these mystery blobs are hiding something.

After analyzing observations of the dusty objects, an international team of researchers, led by astrophysicist Florian Peißker of the University of Cologne, have identified these clumps as potentially harboring young stellar objects (YSOs) shrouded by a haze of gas and dust. Even stranger is that these infant stars are younger than an unusually young and bright cluster of stars that are already known to orbit Sgr A*, known as the S-stars.

Finding both of these groups orbiting so close is unusual because stars that orbit supermassive black holes are expected to be dim and much more ancient. Peißker and his colleagues “discard the en vogue idea to classify [these] objects as coreless clouds in the high energetic radiation field of the supermassive black hole Sgr A*,” as they said in a study recently published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

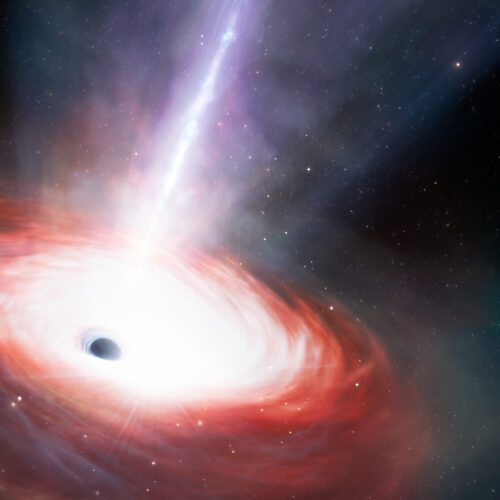

Artist’s animation of the black hole at the center of SDSS1335+0728 awakening in real time—a first for astronomers.

In December 2019, astronomers were surprised to observe a long-quiet galaxy, 300 million light-years away, suddenly come alive, emitting ultraviolet, optical, and infrared light into space. Far from quieting down again, by February of this year, the galaxy had begun emitting X-ray light; it is becoming more active. Astronomers think it is most likely an active galactic nucleus (AGN), which gets its energy from supermassive black holes at the galaxy's center and/or from the black hole's spin. That's the conclusion of a new paper accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, although the authors acknowledge the possibility that it might also be some kind of rare tidal disruption event (TDE).

The brightening of SDSS1335_0728 in the constellation Virgo, after decades of quietude, was first detected by the Zwicky Transient Facility telescope. Its supermassive black hole is estimated to be about 1 million solar masses. To get a better understanding of what might be going on, the authors combed through archival data and combined that with data from new observations from various instruments, including the X-shooter, part of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile's Atacama Desert.

There are many reasons why a normally quiet galaxy might suddenly brighten, including supernovae or a TDE, in which part of the shredded star's original mass is ejected violently outward. This, in turn, can form an accretion disk around the black hole that emits powerful X-rays and visible light. But these events don't last nearly five years—usually not more than a few hundred days.