Eugenics Isn’t Dead—It’s Thriving in Tech

Elon Musk’s calls for a so-called “efficient” US government—including wanting to end the already endangered right to work from home, a disability accommodation for many—are less surprising when you view him as a techno-eugenicist.

The eugenicists of the early 20th century used medical violence like forced hysterectomies in a pseudoscientific campaign to prevent “inferior” immigrants from entering the US, and push certain groups —especially disabled, non-white, and otherwise marginalized people—out of the gene pool.

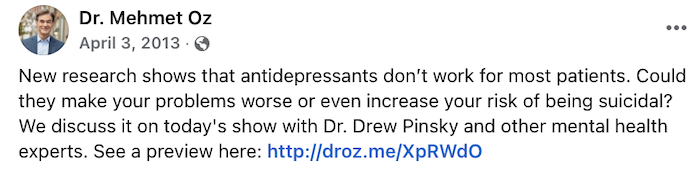

Big Tech successors like Musk and PayPal billionaire-turned-arms dealer Peter Thiel have overtly promoted fraudulent race science, with Musk amplifying users on X who argue that people of European descent are biologically superior. In response to another user’s deleted post suggesting that students at historically Black institutions have lower IQs, Musk posted, “It will take an airplane crashing and killing hundreds of people for them to change this crazy policy of DIE”—diversity, equity, and inclusion, misspelled. In 2016, Thiel buddied up to a prominent white nationalist, and, the same year, was said by a Stanford dorm-mate to have complimented South Africa’s “economically sound” system of racial apartheid.

Data was “deployed by eugenic researchers…to not just track and surveil the poor, [but] to argue for their segregation.”

In her new book Predatory Data, from the University of California Press, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign information sciences and media studies professor Anita Say Chan looks at the history and current use of data in devaluing human beings along eugenicist lines.

I spoke to Chan about the history of predatory data in the United States, why the moral and ethical implications of data collection remain a crucial subject, and how we can fight against its misuse.

Can you share a bit about how data has been used, historically, to cast many disabled people, immigrants, and people of color as being part of the “undeserving poor”—and how that continues today?

For large parts of history, poverty was seen as a largely inevitable phenomenon brought about from a general condition of scarcity. While a “soft” version of poverty as individual failure might have attributed poverty to laziness or immoral behavior, eugenics introduced a “harder” version of a biologically determined undeserving poor as a central object of data collection.

Eugenic researchers labored, and grew a global disinformation movement, across the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to demonstrate poverty not as the result of scarcity or structural exploitations, as labor reformers then argued, but as the result of inherited deficiencies that directly limited intellectual potential, encoded harmful and immoral personal proclivities, and circumscribed economic achievement. In the US, varied datafication methods—from IQ exams and immigrant literacy tests, to criminal databases, biometric archives—were deployed by eugenic researchers in an effort to not just track and surveil the poor, and to argue for their segregation from so-called “fit” populations, but to collect data that eugenicists insisted would prove the higher incidences of moral, physical and mental “unfitness” among the poor.

Our contemporary datafication systems continue to do this today—not only by allowing their growth to be fueled by the expansion of online platforms and social media systems that minimize protections for minoritized users, but by enabling the amplification of political violence against minorities in the interest of protecting their profits.

The incoming Trump administration is very anti-immigrant—not that this country has ever been purely pro-immigration. To go back about a century, how did interpretations of intelligence lead to a dramatic increase in rejections at Ellis Island?

The Immigration Act of 1924 was a historic gain [for eugenicists] that is remembered for imposing a severe national quota system designed to keep non-Anglo-European immigrants out of the United States. Its passage allowed immigration from northern Europe to increase significantly, while Jewish immigration fell from 190,000 in 1920 to 7,000 in 1926, with immigration from Asia—already severely restricted from the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1870s onward—almost completely cut off until the 1950s. But the historic passage of the 1924 act came as a result of direct lobbying from US eugenicists.

Eugenics introduced a “harder” concept of a biologically determined,

undeserving poor as a central object of data collection.

The US psychologist and eugenicist Henry Goddard played an especially critical role. He first introduced the term “moron” in medicine to establish a multi-tiered classification for the “feeble-minded”. With fellow eugenicists, he strove to prove low intelligence as the primary indicator of deficient self-control, criminality, alcoholism, laziness, prostitution, and even political dissent. He advocated intelligence testing for all US immigrants to exclude so-called “unfit” arrivals. In 1913 he began an infamous study on immigrant intelligence that included as assessment questions that he delivered in English to respondents: “What is Crisco?”—the US-made cooking product introduced just two years earlier as an alternative to butter, and “Who is Christy Mathewson?”—an American [baseball] player.

Based on responses to such questions, he classified over 80 percent of his respondents as feebleminded—confirming, as Goddard wrote when the study was published in 1917, “that a surprisingly large percentage of immigrants are of relatively low mentality.” Goddard ended the article by proudly sharing the dramatic expansion in deportations of mentally defective populations from Ellis Island—by 350 percent and 570 percent in 1913 and 1914, respectively—that his study had triggered.

Data has also been used in imagining what a future can look like, such as with the Futurama exhibit at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. How did America’s embrace of eugenics lead to a smart city design being envisioned with only non-disabled people in mind?

The Futurama was General Motors’ celebrated “smart city” exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair. It was also a homage to how streamlining principles, channeled into urban planning and design, could yield enthusiasm and awe for eugenic utopias. This was the sublime perfection that could scale when designers and engineers controlled growth and design to ensure perfection—not only over how the future city functioned, but over the eugenic social future it helped evolve. It’s no accident then, that a 1939 Life Magazine article reveled in the unabashedly fit, tanned, heteronormative, ableist masculinity standardized at the center of the streamlined society when it covered the Futurama.

This was a future utopia where the benefits of intelligent planning and evolutionary progress were driven by eradication of problems of excess, uncertainty, and wasteful heterogeneity—not only in technology but in society at scale. And it drew in an unprecedented audience of some forty-four million visitors—the most of any World’s Fair until the time—with such a promise.

Even during the rise of the eugenics movement in North America, data has also been used as a tool of resistance. Can you talk about the pioneering work at Chicago’s Hull House, and how that can serve as a model today?

Although it’s largely overlooked today, Hull House was broadly recognized at the turn of the century for its leadership in the nineteenth-century urban settlement movement that helped grow more than 400 other settlements in the US, and that played a key role in the passage of key legal reforms from the eight-hour workday, the minimum wage, and the elimination of child labor and workplace safety laws. It was also committed to building research communities and to advancing community-centered data methods.

Intelligence tests for would-be immigrants demanded answers about Crisco—then a brand-new product—and baseball star Christy Mathewson.

Volumes it published, and that were written by women and immigrant authors, like the Hull House Maps & Papers of 1895, not only documented the impacts of sweatshop labor on the largely immigrant families of Chicago’s West Side, but quickly placed them at the forefront of new social science techniques by showcasing the use of innovative data methods from social surveys to color-coded neighborhood wage maps. Such methods later helped establish standard data collection methods for social science professions. Its approach helped to shift the public’s understanding of poverty by emphasizing poverty’s roots in labor exploitation, and political disenfranchisement.

But Hull House’s unique success was importantly grounded in its commitment to developing social coalitions, and its numerous collaborations with labor associations, civic groups, working families and immigrants where it was based in Chicago’s 19th Ward. It’s a reminder of not only of what can be achieved when predatory forms of eugenic data practice are explicitly refused but of the power of alternative data traditions that have long been rooted in justice-based coalition work.

With figures like Elon Musk playing major roles in the upcoming Trump administration, do you think conversations about how data is used have become more important?

I’ve already seen an uptick in communities working to get new laws passed at the local level to require greater public oversight over the acquisition of new surveillance technologies by police and city authorities. My community in Urbana, Illinois, currently has an ordinance [now tabled] before the city council to this end.

These have been commonsense approaches to maintaining public transparency and protecting civil rights, civil liberties, and due process. But they also emerge from a growing awareness that even in normal conditions, it would not be unthinkable to imagine that data collected on targeted individuals by public agencies with the initial intent to promote safety and health could be repurposed for malicious and discriminatory use.

Dozens of US cities began passing laws to prevent facial recognition data capture after 2019 reports revealed that hundreds of millions of driver’s license photos stored in states’ Department of Motor Vehicles databases were being used by ICE to search for immigrants of interest.

Many universities, including my own, refuse to keep records on such data points as which students have DACA status, to prevent undue risks to students and to the educational environment writ large. And, of course, there’s a long history of US eugenic researchers leveraging data pools they were allowed to collect by using public institutions to help monitor populations to pass varied anti-immigration and pro-forced sterilization laws targeting “the unfit” in the name of public health and safety.

I’m heartened to see conversations already re-energized around the political implications of data collection and to see new coalition-making around what resources we might be able to protectively leverage at the local level. This kind of solidarity-making across diverse constituencies, and drawing from traditions in justice-based coalition-making, is what we’re going to need to become well-practiced at.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.