In Trump’s “Energy Dominance” Rhetoric, Environmentalist See an Emerging “Petrostate”

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

As President-elect Donald Trump puts together a team that will ramp up fossil fuel production in a country that is already pumping out more crude oil than any nation in history, critics are beginning to use a term once reserved for reviled foes.

Specifically, they are asking: Is the United States on its way to becoming a petrostate?

Jean Su, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s energy justice program, raised the question after Trump tapped Chris Wright, CEO of the Denver fracking company Liberty Energy, to lead the Department of Energy. Wright accepts that carbon emissions make the planet warmer, but contrary to the scientific consensus, he argues that the financial and quality-of-life benefits of increased fossil fuel production outweigh the risks.

“Picking someone like Chris Wright is a clear sign that Trump wants to turn the US into a pariah petrostate,” Su said in an emailed statement. “He’s damning frontline communities and our planet to climate hell just to pad the already bloated pockets of fossil fuel tycoons.”

Climate scientist Michael Mann offered the same view in an essay soon after the election. “The United States is now poised to become an authoritarian state ruled by plutocrats and fossil fuel interests,” he wrote in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “It is now, in short, a petrostate.”

Economists and political scientists point out that the United States does not fit the classical definition of a petrostate. Its economy is far more diverse than those of nations that are hamstrung by dependence on oil and natural gas. Moreover, the vast majority of the wealth generated by fossil fuel production here goes to private parties—not into government coffers.

And yet, experts concede that the United States behaves like a petrostate at times: for example, in its long-time inaction on climate change and, more recently, in the way it conducts foreign policy as the world’s leading oil and gas exporter. The fossil fuel industry’s influence is bound to be amplified under Trump, who does not view climate change as a serious problem and who describes “energy dominance” as a policy imperative.

“The United States is acting a bit like, I wouldn’t necessarily say a petrostate, but like a state in which the hydrocarbon industry is a huge domestic constituency and source of employment and private sector revenues and now exports,” said Cullen Hendrix, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The oil and gas industry—even by its own reckoning—currently accounts for just 8 percent of the US economy. Trump’s presidency will test whether competing interests—including businesses, states, and citizens that favor a clean energy transition—can exert enough influence to prevent the United States from going down the path that has hobbled the governance and economies of nations that are reliant on a single commodity.

Trump was not successful in permanently quashing the drive for clean energy in his first term. President Joe Biden was able to restore the US’s place in the Paris Agreement negotiations, reverse most of Trump’s deregulatory decisions and pass the nation’s first comprehensive climate legislation.

But Mann, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media, argues that the risks are greater in Trump’s second term that wealthy fossil fuel interests will gain a durable advantage in the US political system.

“This time polluters and plutocrats have made sure they’re ready to hit the ground running,” Mann wrote in an email, pointing to the conservative policy roadmap, Project 2025, written by former Trump administration officials and supporters to guide his agenda. “They won’t waste any time at all eliminating the obstacles to a fossil fuel industry-driven agenda.”

True petrostates typically have state-owned oil companies and seek to maximize revenue as a matter of policy. In Azerbaijan, for example—the country where this year’s international climate talks took place—oil and gas output accounts for more than 90 percent of export revenue and over half of its national budget.

“I think it’s worth remembering that this is not that abnormal for the United States.”

In the United States, private and publicly traded oil and gas companies seek to influence the political process through lobbying and campaign contributions. In 2024, oil and gas industry political giving reached a record $219 million, overwhelmingly favoring Republicans and conservative groups, according to the watchdog group Open Secrets.

But the fossil fuel industry is also woven into the U.S. political fabric in ways that resemble the structure of petrostates. More than 60 percent of the $138 billion in taxes that the fossil fuel industry pays annually goes to state, local and tribal governments, according to a study by the Washington, D.C.-based think tank Resources for the Future, or RFF.

Wyoming gets 59 percent of its state budget from fossil fuel revenue; North Dakota, 29 percent; and Alaska, 21 percent. Other states, though less reliant, take in staggering sums, led by Texas, at $14.6 billion annually; California, $7.8 billion; and Pennsylvania, $4.4 billion. And the money going into state coffers reflects the far larger impact the industry is having on state economies and jobs.

Because institutions like the Electoral College and the US Senate give states outsized power compared to their populations, fossil fuel-reliant regions can hold considerable sway over national politics and policy. For example, political observers say that part of the reason Vice President Kamala Harris talked little about the climate accomplishments of her administration during her presidential campaign, and instead repeated her pledge not to ban fracking, was a vain effort to win the swing state of Pennsylvania, the nation’s No. 2 natural gas producer.

The shape of current US climate policy was dictated by the political realities of the Senate, where it would be impossible to get the 66 votes needed to ratify a conventional climate treaty or 60 votes to pass substantive climate legislation. The Obama administration helped design a Paris agreement that contained no binding legal obligations, and therefore would not require Senate ratification. And the Biden administration’s climate legislation was an incentives package wrapped in a spending bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, which required only a bare majority for passage (and got one only with Harris’ tie-breaking vote).

“The US has always had a hard time enacting climate policy,” said Daniel Raimi, a fellow at RFF who led its fossil fuel revenue study. “The Inflation Reduction Act was the exception rather than the rule, and it’s also a very unusual kind of climate policy. Most of the rest of the world use carbon pricing or regulatory tools. We couldn’t do any of that because of the political dynamics, so we went for the subsidy-based approach.”

But now, the Trump administration is intent on unraveling those policies. Trump’s job is made easier because the policies weren’t the product of a bipartisan consensus for climate action.

“I think it’s worth remembering that this is not that abnormal for the United States,” Raimi said. “Unfortunately, this is kind of where we have been for most of the last few decades.”

Fracking, which unleashed a flood of oil and gas on the US market beginning in 2010, laid the groundwork for Trump’s “energy dominance” agenda.

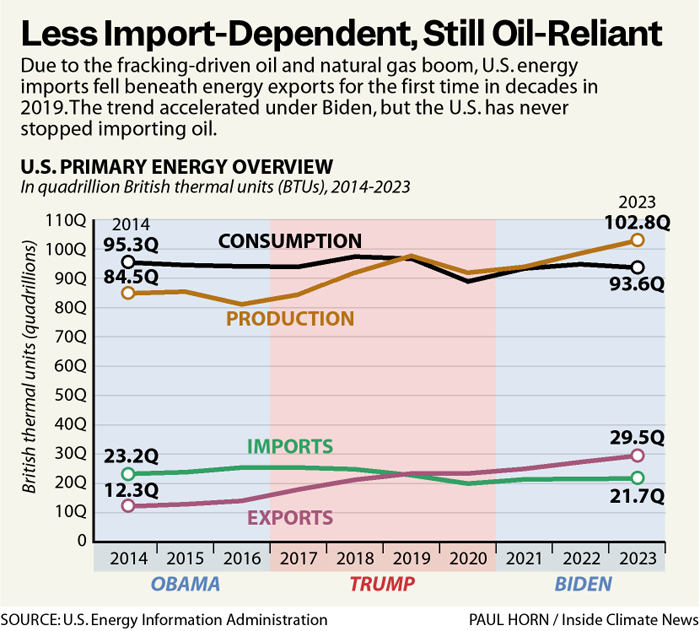

Trump liked to say that the United States became energy independent on his watch, surpassing Russia and Saudi Arabia in oil production in 2018 and the following year, becoming a net exporter of energy for the first time in more than 60 years. But those trends began under Obama and have accelerated under Biden, with the United States producing 12.9 million barrels per day of crude oil in 2023, more than any other nation in history.

Mammoth facilities have been built in recent years to export liquefied natural gas, or LNG. And in 2015, Congress lifted a four-decade-old ban on US exports of crude oil, responding to the oil industry’s plea that it needed to be able to compete with petrostates for the nation’s own welfare. “Today’s vote starts us down the path to a new era of energy security,” American Petroleum Institute CEO Jack Gerrard said at the time. American producers, he said, “would be able to compete on a level playing field with countries like Iran and Russia, providing security to our allies.”

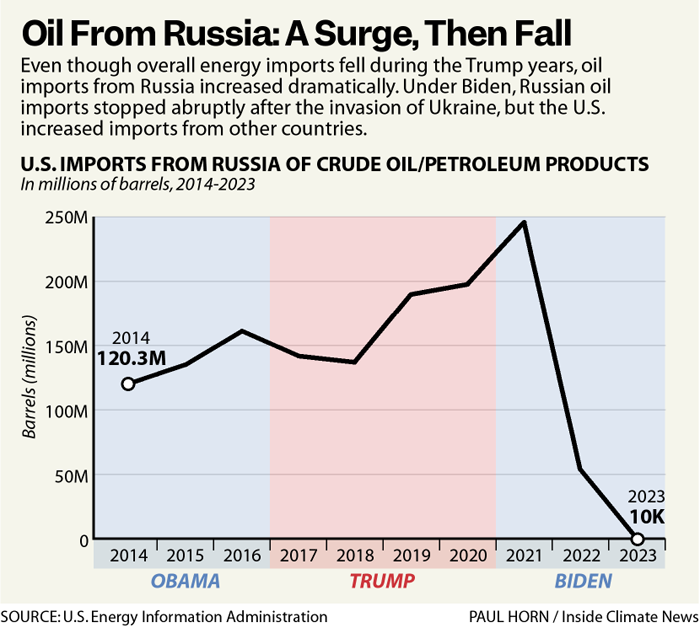

Biden put that concept into action after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, increasing LNG shipments to the European Union to undercut Russia’s role as a crucial energy supplier to the continent. For the past three years, the United States has provided half of the EU’s LNG supplies, a cushion that has helped allies cope with a precipitous fall in the energy supply from Russia.

Early this year, Biden paused approval of new LNG ports pending a study of their greenhouse gas impact—but a federal judge lifted that moratorium and Trump plans to end it altogether, potentially clearing the way for 20 proposed new LNG terminals. LNG could play a bigger foreign policy role, even if Trump should succeed in ending the Ukraine war “in 24 hours,” as he has promised.

“It seems clear that the second Trump administration is going to want to use this energy leverage to exact concessions from Europe on a variety of fronts,” Hendrix said. “It might be increasing military spending, or more military spending earmarked for U.S. arms exports, or more guarantees to purchase more U.S. exports generally.”

The EU may be ready to deal. The day after the election, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen proposed that the EU might be able to head off Trump tariffs by agreeing to buy more LNG from the United States.

A number of forces may work against the oil and gas industry’s interests during the new Trump administration.

Other industries may succeed in holding off some of the planned regulatory rollbacks, like auto manufacturers, who have invested billions of dollars in electric vehicle and battery plants in anticipation of the clean energy transition they see taking place globally.

States that have new clean energy projects or a long-term commitment to fighting climate change will make their voices heard. “We are going to move forward in the United States, state by state, county by county, city by city, in continuing our tremendous dynamic growth of our clean energy economy,” said Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington in a news conference after the election.

Environmentalists, landowners and fishing operations already are in court fighting the construction of new LNG terminals. Judges have ruled against three LNG projects so far this year, indicating Trump will not be able to make new ports appear on the Gulf Coast overnight.

And finally, some experts rightly acknowledge that Trump’s own energy policy vision may be at odds with itself. Trump frequently said he wanted to return to the “beautiful number” of $1.87 per gallon gasoline—where prices bottomed out during his final year in office.

Gasoline prices were so low in 2020, however, because the global economy had ground to a standstill due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Crude oil prices, now more than $74 per barrel, would have to plummet to $20 per barrel—as they did in 2020—to bring pump prices so low, experts say. That could stop “drill, baby, drill” in its tracks. Exxon Mobil has said its break-even point—the oil price at which it can cover its costs of production—is $35 per barrel; and Wells Fargo estimated last year that break-even for companies that frack in US shale basins is $54 per barrel.

The realities of the free market, as well as democratic institutions, may yet prevent the United States from slipping into the realm of petrostates. Nevertheless, the 2024 election has driven home to many how fossil fuel abundance has made the road to climate action harder in the United States.

“Imagine a United States that was as oil-starved as China,” Hendrix said. “You’d see a lot more sustained emphasis on renewables, going back to the 1990s, if not the 1980s.

“Instead, what we have is this kind of domestic political competition between a coalition that supports renewable energy and a coalition that supports fossil fuels,” he said. “And Trump’s election suggests to me that fossil fuels are the winners in the short term.”