Gravitas Ventures Acquires U.S. and Canadian Rights to Religious Horror ‘Inhabitants’ (EXCLUSIVE)

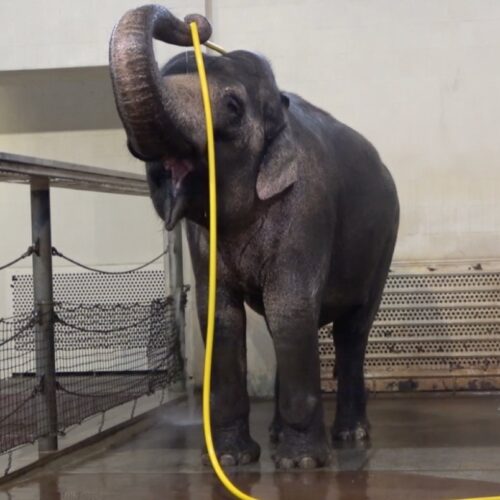

An Asian elephant named Mary living at the Berlin Zoo surprised researchers by figuring out how to use a hose to take her morning showers, according to a new paper published in the journal Current Biology. “Elephants are amazing with hoses,” said co-author Michael Brecht of the Humboldt University of Berlin. “As it is often the case with elephants, hose tool use behaviors come out very differently from animal to animal; elephant Mary is the queen of showering.”

Tool use was once thought to be one of the defining features of humans, but examples of it were eventually observed in primates and other mammals. Dolphins have been observed using sea sponges to protect their beaks while foraging for food, and sea otters will break open shellfish like abalone with rocks. Several species of fish also use tools to hunt and crack open shellfish, as well as to clear a spot for nesting. And the coconut octopus collects coconut shells, stacking them and transporting them before reassembling them as shelter.

Birds have also been observed using tools in the wild, although this behavior was limited to corvids (crows, ravens, and jays), although woodpecker finches have been known to insert twigs into trees to impale passing larvae for food. Parrots, by contrast, have mostly been noted for their linguistic skills, and there has only been limited evidence that they use anything resembling a tool in the wild. Primarily, they seem to use external objects to position nuts while feeding.

© Urban et al./Current Biology

We tend to think of agriculture as a human innovation. But insects beat us to it by millions of years. Various ant species cooperate with fungi, creating a home for them, providing them with nutrients, and harvesting them as food. This reaches the peak of sophistication in the leafcutter ants, which cut foliage and return it to feed their fungi, which in turn form specialized growths that are harvested for food. But other ant species cooperate with fungi—in some cases strains of fungus that are also found growing in their environment.

Genetic studies have shown that these symbiotic relationships are highly specific—a given ant species will often cooperate with just a single strain of fungus. A number of genes that appear to have evolved rapidly in response to strains of fungi take part in this cooperative relationship. But it has been less clear how the cooperation originally came about, partly because we don't have a good picture of what the undomesticated relatives of these fungi look like.

Now, a large international team of researchers has done a study that traces the relationships among a large collection of both fungi and ants, providing a clearer picture of how this form of agriculture evolved. And the history this study reveals suggests that the cooperation between ants and their crops began after the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs, when little beyond fungi could thrive.

© pxhidalgo

We tend to think of agriculture as a human innovation. But insects beat us to it by millions of years. Various ant species cooperate with fungi, creating a home for them, providing them with nutrients, and harvesting them as food. This reaches the peak of sophistication in the leafcutter ants, which cut foliage and return it to feed their fungi, which in turn form specialized growths that are harvested for food. But other ant species cooperate with fungi—in some cases strains of fungus that are also found growing in their environment.

Genetic studies have shown that these symbiotic relationships are highly specific—a given ant species will often cooperate with just a single strain of fungus. A number of genes that appear to have evolved rapidly in response to strains of fungi take part in this cooperative relationship. But it has been less clear how the cooperation originally came about, partly because we don't have a good picture of what the undomesticated relatives of these fungi look like.

Now, a large international team of researchers has done a study that traces the relationships among a large collection of both fungi and ants, providing a clearer picture of how this form of agriculture evolved. And the history this study reveals suggests that the cooperation between ants and their crops began after the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs, when little beyond fungi could thrive.

© [CDATA[pxhidalgo]]

Enlarge / Long covid activists attend the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies hearing on the "Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request for the National Institutes of Health," in Dirksen building on May 23, 2024. (credit: Getty | Tom Williams)

As a summer wave of COVID-19 infections swells once again, a study published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine offers some positive news about the pandemic disease: Rates of long COVID have declined since the beginning of the health crisis, with rates falling from a high of 10.4 percent before vaccines were available to a low of 3.5 percent for those vaccinated during the omicron era, according to the new analysis.

The study, led by Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research at the VA Saint Louis Health Care System, used data from a wealth of health records in the Department of Veterans Affairs. The researchers ultimately included data from over 440,000 veterans who contracted COVID-19 sometime between March 1, 2020, and January 31, 2022, as well as over 4.7 million uninfected veterans who acted as controls.

Al-Aly and colleagues divided the population into eight groups. People who were infected during the study period were divided into five groupings by the dates of their first infection and their vaccination status. The first group included those infected in the pre-delta era before vaccines were available (March 1, 2020, to June 18, 2021). Then there were vaccinated and unvaccinated groups who were infected in the delta era (June 19, 2021, to December 18, 2021) and the omicron era (December 19, 2021, and January 31, 2022). The uninfected controls made up the final three of eight groups, with the controls assigned to one of the three eras.

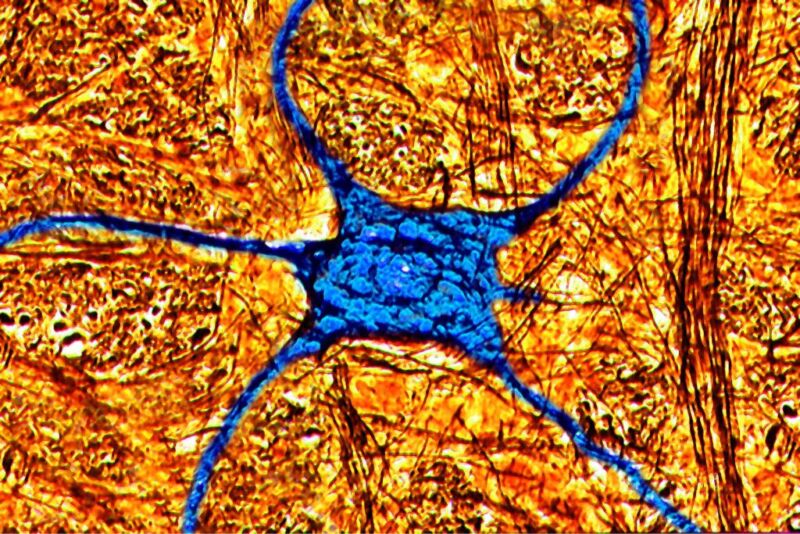

Enlarge / Human Neuron, Digital Light Microscope. (Photo By BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images) (credit: BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

“Language is a huge field, and we are novices in this. We know a lot about how different areas of the brain are involved in linguistic tasks, but the details are not very clear,” says Mohsen Jamali, a computational neuroscience researcher at Harvard Medical School who led a recent study into the mechanism of human language comprehension.

“What was unique in our work was that we were looking at single neurons. There is a lot of studies like that on animals—studies in electrophysiology, but they are very limited in humans. We had a unique opportunity to access neurons in humans,” Jamali adds.

Jamali’s experiment involved playing recorded sets of words to patients who, for clinical reasons, had implants that monitored the activity of neurons located in their left prefrontal cortex—the area that’s largely responsible for processing language. “We had data from two types of electrodes: the old-fashioned tungsten microarrays that can pick the activity of a few neurons; and the Neuropixel probes which are the latest development in electrophysiology,” Jamali says. The Neuropixels were first inserted in human patients in 2022 and could record the activity of over a hundred neurons.

Science grants are essential resources for researchers, educators, and institutions looking to advance scientific knowledge and innovation. These grants provide the necessary funding to conduct research, develop educational programs, and support scientific endeavors. As an expert in Science and Education, I will guide you through the intricacies of science grants, their importance…

In the realm of Health & Wellness, supporting your immune system is crucial for maintaining overall well-being and preventing illness. As an expert in Health & Wellness, I will provide comprehensive insights into how you can naturally boost your immune system through lifestyle choices, nutrition, and wellness practices. This guide aims to help you understand the importance of immune system support…

Enlarge / Scientists have observed wound care and selective amputation in Florida carpenter ants. (credit: Danny Buffat/CC BY-SA)

Florida carpenter ants (Camponotus floridanus) selectively treat the wounded limbs of their fellow ants, according to a new paper published in the journal Current Biology. Depending on the location of the injury, the ants either lick the wounds to clean them or chew off the affected limb to keep infection from spreading. The treatment is surprisingly effective, with survival rates of around 90–95 percent for amputee ants.

“When we're talking about amputation behavior, this is literally the only case in which a sophisticated and systematic amputation of an individual by another member of its species occurs in the animal kingdom,” said co-author Erik Frank, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Würzburg in Germany. “The fact that the ants are able to diagnose a wound, see if it's infected or sterile, and treat it accordingly over long periods of time by other individuals—the only medical system that can rival that would be the human one."

Frank has been studying various species of ants for many years. Late last year, he co-authored a paper detailing how Matabele ants (Megaponera analis) south of the Sahara can tell if an injured comrade's wound is infected or not, thanks to chemical changes in the hydrocarbon profile of the ant cuticle when a wound gets infected. These ants only eat termites, but termites have powerful jaws and use them to defend against predators, so there is a high risk of injury to hunting ants.

Designing a home that accommodates the needs of your pets while maintaining style and functionality can be a rewarding endeavor. As an expert in Home Living, I will guide you through the principles of pet-friendly home designs, offering tips and ideas to create a harmonious living space for both you and your furry friends. This article aims to provide valuable insights into creating a pet-friendly…

Enlarge / Ten milligram tablets of the hyperactivity drug, Adderall, made by Shire Plc, is shown in a Cambridge, Massachusetts pharmacy Thursday, January 19, 2006. (credit: Getty | Jb Reed)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Thursday warned that a federal indictment of an allegedly fraudulent telehealth company may lead to a massive, nationwide disruption in access to ADHD medications—namely Adderall, but also other stimulants—and could possibly increase the risk of injuries and overdoses.

"A disruption involving this large telehealth company could impact as many as 30,000 to 50,000 patients ages 18 years and older across all 50 US states," the CDC wrote in its health alert.

The CDC warning came on the heels of an announcement from the Justice Department Thursday that federal agents had arrested two people in connection with an alleged scheme to illegally distribute Adderall and other stimulants through a subscription-based online telehealth company called Done Global. The company's CEO and founder, Ruthia He, was arrested in Los Angeles, and its clinical president, David Brody, was arrested in San Rafael, California.

Enlarge (credit: Buena Vista Images)

Lots of animals communicate with each other, from tiny mice to enormous whales. But none of those forms of communication share even a small fraction of the richness of human language. Still, finding new examples of complex communications can tell us things about the evolution of language and what cognitive capabilities are needed for it.

On Monday, researchers reported what may be the first instance of a human-like language ability in another species. They have evidence that suggests that elephants refer to each other by individual names, and the elephant being referred to recognizes when it's being mentioned. The work could benefit from replication with a larger population and number of calls, but the finding is consistent with what we know about the sophisticated social interactions of these creatures.

We use names to refer to each other so often that it's possible to forget just how involved their use is. We recognize formal and informal names that refer to the same individual, even though those names often have nothing to do with the features or history of that person. We easily handle hundreds of names, including those of people we haven't interacted with in decades. And we do this in parallel with the names of thousands of places, products, items, and so on.