Mark Ruffalo, Harper Steele, Brittney Griner and Viet Thanh Nguyen Honored at ACLU SoCal Bill of Rights Awards

As Americans cast their votes in an election dominated by debates over inflation and the cost of living, a ballot measure in Vice President Kamala Harris’ home state is dividing the Democratic Party on the issue of how to address skyrocketing rents.

Proposition 33—dubbed the Justice for Renters Act—would repeal the state’s controversial Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, which for decades has restricted local governments’ ability to cap rent increases. Currently, Costa-Hawkins blocks counties and cities from imposing rent controls on apartments, condos, and single-family homes built after a certain date—1995 in much of the state, but years earlier in some cities, such as San Francisco. It also prohibits vacancy control, meaning that even landlords who are subject to rent controls can raise rents up to the market rate when a new tenant moves in.

Some cities have already enacted new rent control plans in anticipation of Prop. 33 passing. In October, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to approve legislation that would expand rent control to approximately 16,000 additional units if the initiative passes.

In some ways, Prop. 33 is similar to President Joe Biden’s proposal this past summer to cap annual rent increases at 5 percent over the next two years for large landlords who want to obtain federal tax breaks. Two weeks after it was rolled out, speaking to a crowd in Atlanta, Harris appeared to voice support for the president’s plan, vowing to “take on corporate landlords and cap unfair rent increases.” But since then, according to the Nation, she has largely left promises for direct tenant protections out of her public statements. The outlet observed that instead of renters, Harris seemed to be focusing on homeowners, pushing policies like tax incentives for developers to build for first-time homebuyers.

Harris’ reluctance to embrace rent control may mark a small victory for YIMBYs, the “yes-in-my-backyard” pro-housing movement that first emerged in San Francisco in the 2010s as a more market-based approach to the housing affordability crisis. YIMBYs, many of whom are Democrats, have largely opposed Prop. 33, arguing it would cause new rental construction to grind to a halt. An analysis by California YIMBY, an advocacy group focused on ameliorating the state’s housing shortage, argued that passing the measure “will likely worsen housing affordability by empowering NIMBY jurisdictions to block new housing.”

NIMBY, a largely pejorative label meaning “not in my backyard,” describes locals who oppose construction and redevelopment in their neighborhoods—ranging variously from affordable housing, to homeless shelters, to luxury condos, to public transportation infrastructure. According to Matthew Lewis, the communications director at California YIMBY, NIMBYs include residents from across the political spectrum. While conservative NIMBYs might oppose new buildings to maintain the status quo or inflate property values in their neighborhoods, many left-aligned NIMBYs strongly oppose market-based development out of fears over gentrification or ideological commitments. Between those poles lies a significant group of mainstream liberal NIMBYs, who, as New York Magazine’s Curbed puts it, “believe in affordable housing until it’s in their neighborhood.” In 2022, Barack Obama called them out, specifically arguing that resistance to “affordable, energy-sustainable, mixed-use and mixed-income communities” contributes to the housing crisis.

“When you have very right-wing NIMBYs agreeing with left NIMBYs that we should do all the things necessary to prevent more homebuilding, it kind of makes you go, huh?” Lewis said.

For Lewis, the story of a rent-controlled city like San Francisco characterizes the debate. According to the city’s housing plan, about 70 percent of San Francisco renters live in rent-stabilized units, built before June 1979. But this hasn’t helped the affordability crisis, as the percentage of the city’s households who were rent-burdened—that is, who spent more than 30 percent of their income on rent—increased by roughly 15 percent from 1990 to 2015 for residents making 50 to 80 percent of the median San Francisco income. And according to the Public Policy Institute of California and the California Housing Partnership, in 2024, over half of all renters in the state—roughly 3 million residents—are rent-burdened.

“I think our opponents on the left misconstrue that rent control is this mechanism of broad affordability,” Lewis said. “But what it’s supposed to do is provide stability and security of tenure for lower income tenants. In a city like San Francisco, what you end up with is millionaires living in rent-controlled housing.”

To get it right, Lewis suggests that the city first has to “unleash a building boom” by constructing housing and renting it out at market rate so developers can recoup investment costs and continue to build. “Then when those buildings become eligible for rent control—after 15 or 20 years—you have this abundant supply of rent-stabilized units because you’ve never stopped building,” he argues.

Many housing justice advocates reject that argument. In a 2021 article for Housing is a Human Right, a prominent group now backing Prop. 33, Patrick Range McDonald wrote that such market-based strategies resemble the real estate industry’s failed “trickle-down housing policy” that has led to the ongoing crisis. Comparing it to giving tax cuts to the rich, McDonald wrote that “corporate landlords and major developers will generate billions in revenue by charging sky-high rents for market-rate apartments, making massive profits off the backs of the middle and working class.”

In a May 2024 analysis charging that California YIMBY has sided with corporate landlords to defeat Prop. 33, McDonald wrote that this YIMBY proposal of “filtering” actually “fuels gentrification and displacement in working-class neighborhoods, including communities of color,” since, he says, developers will only build luxury housing to maximize profits.

For his part, Lewis contends that many of Prop. 33’s leftist supporters are acting in direct opposition to affordability by arguing that only government-funded social housing projects can solve the problem. “I think that this is where YIMBYs really part ways with the left,” he said. “The market can just move substantially faster than the government can, if you let it.” While Lewis concedes that the government should play a substantial role in providing subsidized housing for low-income residents, he says that “you can’t have a functioning system where the government is basically shutting down housing production for most of the market.”

Rent control, Lewis says, contributes to the housing shortage. He points to New York City, which has an estimated 26,000 older, rent-stabilized units that are empty, according to findings from the 2023 survey, because limits on rent increases make it difficult for landlords to keep up with maintenance costs and building codes.

The debate is raging among economists, too. A University of Chicago poll found that an overwhelming 81 percent of economists surveyed opposed rent control. But in 2023, 32 prominent economists signed a letter supporting nationwide rent control. The document referred to a 2007 study following rent control policies for 30 years across 76 cities in New Jersey. It found “little to no statistically significant effect of moderate rent controls on new construction.” There is also research connecting housing supply reductions to systemic loopholes, such as exceptions that allow landlords to evict all tenants in a building to convert their rental units into market-rate condos.

Shanti Singh, the legislative and communications director at Tenants Together, a coalition of local tenant organizations in California, argues that rent control and new development can work in concert. “We fight for housing that folks can afford. Millions and millions of people’s wages simply are not anywhere close to meeting market rates,” Singh says. “We’re fighting for people living in crowded conditions, people who are homeless, and people one step away from being homeless.”

It’s not tenant advocates but current laws restricting rent control that are the real problem, Singh claims: “Because of Costa-Hawkins, we are actually bleeding the supply of rent-controlled housing that’s affordable at below market rates. That’s a unit that you’ve lost. That’s the supply loss.”

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there is a shortage of nearly one million affordable rental units in California for “extremely low income renters,” or residents who earn less than 30 percent of the state median income. “There’s a huge issue with folks with disabilities on fixed incomes, including seniors, who need accessible housing,” Singh says. They can’t access rent-controlled housing in places like San Francisco because the units are too old to have the necessary accommodations—they’re all constructed before 1979.

Instead of working on legislation that will solve the affordability crisis, Singh says that many YIMBYs are “leaving a status quo in place that’s untenable” by bringing up “insane hypothetical scenarios.”

Susie Shannon, the policy director at Housing Is A Human Right—which has put over $46 million into its support for Prop. 33—says Tony Strickland is one of these hypotheticals. Strickland, a conservative city council member in wealthy Huntington Beach, is an example of a NIMBY to many pro-development advocates. YIMBYs argue that he would use rent control laws like Prop. 33, if passed, to circumvent California’s affordable housing mandates by setting unreasonably low rent caps designed to stifle new housing development, according to the Orange County Register.

Shannon pointed to an op-ed by Strickland, in which the councilman said his words had been taken out of context and affirmed that he has been “a lifelong opponent of rent control.” He clarified that he does support some language in the ballot measure that stops the state from using the court system to block local rent control decisions. Strickland did not respond to a request for comment from Mother Jones.

Dean Preston, a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and the number one enemy of several California pro-development groups, says the amount of money backing the campaign against Prop. 33—over $120 million according to the Los Angeles Times—is telling. The two largest opposition donors are the California Apartment Association at nearly $89 million and the California Association of Realtors at $22 million.

“What has sucked up a lot of the debate from [Prop 33] opponents is discussing…what impacts rent control has on construction financing,” Preston says. “But what’s really driving the opposition is vacancy control”—the possibility that with the repeal of Costa-Hawkins, local governments would limit the amount a landlord could increase rents between tenants.

Preston believes that without vacancy control, cities are essentially powerless to regulate rents. “That’s why it is worth it for the California Association of Realtors, the California Apartment Association, and the landlord lobby to invest,” he says.

While more than 650,000 people in the United States experience homelessness on any given night and living without shelter has increasingly become a crime, everyone I talked to maintains that there is a way to solve the housing crisis.

For Lewis, it’s expanding funding for programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, which offers developers incentives for making a portion of their construction affordable for low-income residents. He also favors upzoning to increase housing density by allowing more multifamily units in areas previously reserved for single-family homes.

For tenant advocates like Singh and Preston, it’s about the increased dialogue around housing on the national stage, as well as the repeated attempts to create a federal social housing authority.

“I think there’s a sense within the tenant movement in California that it is inevitable at some point that Costa-Hawkins will be repealed because most people support rent control,” Preston says. “I hope Prop. 33 passes, but if it doesn’t, I expect it’ll be back on a future ballot and in future legislative efforts.”

I was doom-scrolling on X a few months ago when a video about Oakland, California, caught my eye: “Do you know your recaller?” it asked, before an image of a talking white-haired man with a yellow tie flashed across the screen. “Let’s find out.”

I’d been curious about the recalls in Oakland for a while: Mayor Sheng Thao and District Attorney Pamela Price, both progressive women of color, face elections that could drive them out of office. Though their critics have come at them for many reasons, from allegations of nepotism and mismanagement to an FBI raid on Thao’s home, these recall campaigns have largely been driven by community concerns about crime: In Oakland, as in much of the country, many people don’t feel safe right now, even if the data shows that violence dropped significantly this year. I’d already spoken with some of the city’s recall leaders, many of whom are also people of color, hoping to understand why. But I had never seen the man with the yellow tie before. He worked in PR.

Republicans and moderate Democrats are using crime fears to whip up support for their causes, even as extreme pandemic-era spikes in violence fade.

“Sam Singer is the predator’s press man, the bad guy’s good guy,” the video’s anonymous narrator told me, listing a few of Singer’s achievements in the San Francisco Bay Area, particularly in crisis communications. After a Chevron refinery caught fire in Richmond and its noxious fumes sent thousands of people to the emergency room, the oil company hired him to manage its reputational damage. The San Francisco Zoo did the same after a tiger jumped out of its cage and killed a teenager. And in 2019, Singer did PR for the house-flipping company Wedgewood during its standoff with a group of formerly unhoused Black moms squatting with their children in one of the company’s vacant Oakland homes.

Journalists have described Singer as “the master of disaster” and “one of the most influential behind-the-scenes shapers of public opinion in the Bay Area.” He’s repped Facebook, Jack in the Box, and the 49ers, among others. These days, Singer does PR for the Oakland police union; he has said repeatedly that he does not work for the recall campaigns, but he tweets daily about crime in the city and his belief that Thao and Price should be removed from office, and he has a lot of sway with reporters. The video on X struck a conspiratorial note, questioning whether moneyed interests had hired Singer this election season to create “a negative perception of Oakland in the press,” which could help the recalls. Is someone “paying this high-priced spin doctor,” it added, “to talk shit about Oakland?”

Intrigued, I called up some progressives in the city to see what they had to say about Singer. “He came out of nowhere to start attacking me” on social media, DA Price told me, adding that she had heard he was a “hired gun.”

“He’s a central figure in a larger network who are working together to ensure that a certain group of people remains in power,” said Leigh Hanson, chief of staff for Mayor Thao.

“When it comes to the messaging behind the recalls, he is the person,” added Chaney Turner, a delegate for the California Democratic Party.

He’s “using doom-loop narratives to manipulate pain, fear, and trauma, to push a right-wing agenda,” said Cat Brooks, who leads the nonprofit Anti Police-Terror Project.

“He is a spin doctor in the realest sense of the word,” said Tur-Ha Ak, another co-founder of that group.

“The mouthpiece,” said civil rights lawyer Walter Riley.

“The architect,” said City Councilmember Carroll Fife.

They could not offer any proof that Singer is connected with the recall campaigns; the leaders of the recall committees say flatly that he is not working for them. And in any case, even if Singer is the doom-loop mouthpiece that the city’s progressives suspect, he certainly is not acting alone. In Oakland and around the country, there is no shortage of people retailing in bad vibes: Republicans and moderate Democrats are using crime fears to whip up support for their causes, even as extreme pandemic-era spikes in violence—like the one experienced in Oakland—fade. “You can’t walk across the street to get a loaf of bread. You get shot, you get mugged, you get raped,” Donald Trump said at a campaign event, though FBI data showed that US murders fell at the fastest pace ever recorded last year and were still falling in 2024.

None of this is new: Inflated crime rhetoric can benefit lots of people; politicians get votes, police get funding, journalists get clicks. It’s been so consistent over the decades that some academics don’t even define “crime waves” as an actual increase in crime—they define it as an increase in public fear of crime, or public attention to it. “There is essentially no relationship between the patterns of crime coverage you see in the press and the amount of crime in the streets. They’re not related,” said Vincent Sacco, a sociologist in Canada who wrote the book When Crime Waves. Nationally, “we’re at essentially a 50-year-low on crime,” said Cristine Soto DeBerry, who leads the Prosecutors Alliance of California. “And everybody is like, ‘Crime has never been worse!’ The media is a huge part of why people feel that way.”

A day after the X video came out, Singer retweeted it. “We’re going to use this as a promotional video,” he wrote. But when I reached out to him for an interview, he demurred: “I don’t work for either of the recall campaigns…so I am not the right person to speak with about them,” he replied. Journalists told me that Singer is an easy guy to talk with, that he’d been profiled numerous times in the past. But for once, the PR professional did not want to talk. Singer is just “like every other neighbor you see out there tweeting about the recall,” said Seneca Scott, who leads the campaign against Thao. He added that Singer was doing it in his capacity as a “private citizen,” though Singer, unlike other citizens, also works for the Oakland police union, a client that badly wants Thao to step down. He “has nothing to do with the recall,” said Brenda Grisham, who leads the campaign against Price. “I’m not cool with people giving other people credit for the blood and sweat I’ve put into this.”

In the days surrounding my interview request, Singer tweeted constantly about these elections. “Crime is up in Oakland, no question,” he told me in an email, linking to a story about several shootings. He also sent me a press release about a recall campaign ad.

As I dug around, I heard from people who wanted me to write about Singer but worried about speaking on the record. Someone even sent me an anonymous email, linking to information about how Singer influences the media, but they didn’t want to be identified because they interact with him professionally. Progressives complain that the recallers have been less than forthright about the powerful white people funding and otherwise supporting them. “Folks need to understand who’s behind it because they have created this façade,” Ak said. “They put Black people in front of this, and they’re not identifying who’s behind it.” (Scott and Grisham are Black; Singer is white, as are some of the recalls’ biggest funders.) Ak went on: “Without the Sam Singers, these folks would be impotent, they wouldn’t really mean much…The only reason they get any traction is because the Sam Singers amplify their message. The Sam Singers are helping them to get media.”

Both Thao and Price are unhappy with the news coverage. Reporters at local, national, and even international outlets have written critically about their leadership, and the San Francisco Chronicle recently endorsed their recalls. Progressives continue to suspect that Singer is working behind the scenes to help shape how people in the city think about crime. “We the people want to know,” said Pecolia Manigo, who leads the social justice collaborative Oakland Rising, “how do you get as much media coverage as you get? Let’s see your receipts.”

Margaret Singer was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who studied the psychology of cults. After the Korean War in the 1950s, she counseled brainwashed prisoners of war. Then she was called to testify in the 1976 trial of Patty Hearst, who after her abduction by the Symbionese Liberation Army joined the group in robbing a San Francisco bank. Singer interviewed thousands of former and current cult members during her career, from survivors of Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple to members of the Branch Davidians after the deadly Waco siege. “Under the right circumstances we all can be manipulated,” she once said.

Her son, Sam, born in 1957, became fascinated by the news industry, he explained in a Facebook post, partly because of all the reporters who used to call to talk with his mom. At Berkeley High, Sam edited the paper and enjoyed the job’s competitive nature: He’d often run to the city’s Daily Gazette to “show them that I had beaten them on stories at the school board from the night before,” he told the trade magazine PR Week. Straight out of high school, the Gazette hired him as a copy boy, then as a reporter six months later. His editor Harvey Myman was impressed by his ability to listen—a skill that Sam seemed to have picked up while watching Margaret’s therapy sessions at their kitchen table. “He gets it from his mother,” Myman told the Richmond Confidential, which profiled Singer in 2014. “Sam has always been a very keen observer and understands people very well.” After grad school at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, Singer returned to Berkeley when he was 26 and took over the Gazette as editor before it folded about a month later.

“Under the right circumstances we all can be manipulated,” Margaret Singer once said.

Soon, Singer pivoted to politics and PR. As press secretary to Nevada Gov. Richard Bryan during Bryan’s run for Senate, he realized he had a knack for talking with reporters. “If you can understand the news business from one side, you can understand it from the other,” he told PR Week. He opened a PR company alongside Larry Kamer, whom he met during a political campaign in California, and eventually started his own shop, Singer Associates, representing not just politicians but also corporations, government agencies, and anyone in need of crisis management. Over the years, that’s included the likes of Nike, Walmart, Bank of America, Williams-Sonoma, Sony, Levi Strauss & Co., Marriott Hotels, San Francisco International Airport, 24 Hour Fitness, and the Salvation Army, among many others. He was a spokesperson for the Bohemian Club, an exclusive fraternity that’s been rumored over the years to include some of the world’s most powerful people, from William Randolph Hearst to the Koch brothers and both President Bushes. When something blows up, you better call Sam Singer: “It’s almost a cliché in our world,” a longtime city politico told SF Weekly. (Singer’s son James is a spokesperson for Kamala Harris.)

Singer’s success, journalists have written, stems from his close relationships with reporters and columnists at major news outlets, including the Chronicle (another former client). “Sam understands what news is and how his clients’ needs and objectives fit into the definition of news,” PR strategist Chuck Finnie told the Richmond Confidential. After the Chevron fire, Singer even started a newspaper with Chevron funding. The Richmond Standard, as it’s called, still covers the city’s news with a smattering of positive stories about Chevron.

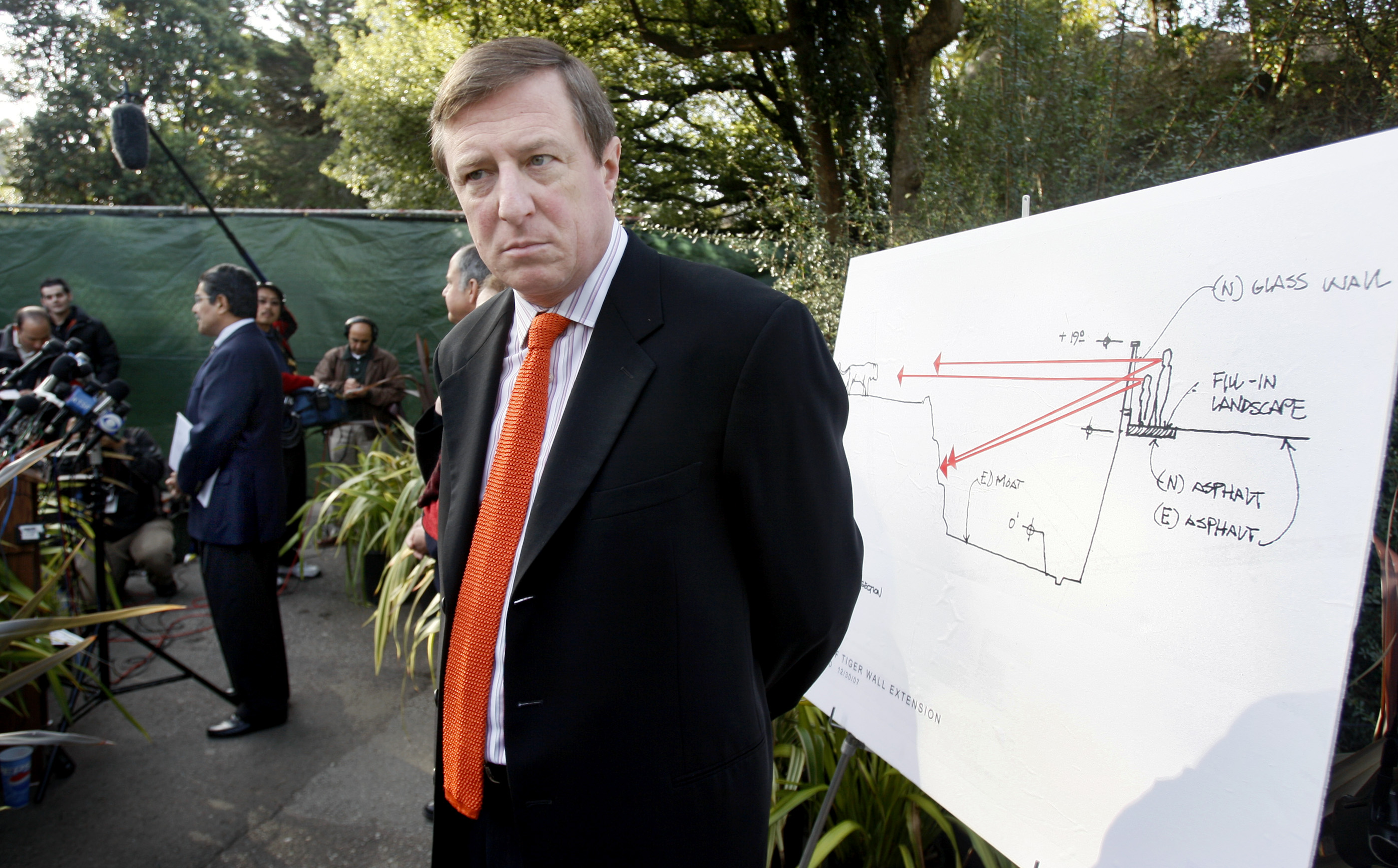

Singer’s success also stems from his keen ability to “turn his client into a sympathetic victim while vilifying his opponents,” then-editor Robert Gammon wrote for Alameda Magazine. After a tiger at the San Francisco Zoo jumped over a wall that was four feet lower than recommended, killing a 17-year-old-old named Carlos Sousa Jr. and injuring two of his friends, Singer urged the zoo to put up signs warning future visitors not to tease the animals. “We knew journalists would ask if they taunted the animals,” he said of the teens. “And we’d say, ‘We don’t know, but we have enough information that we believe it was a possibility.’” The New York Post soon wrote that the friends carried slingshots at the time of the mauling, citing an anonymous source, and that an empty vodka bottle was found in their car. The friends sued following other press coverage, accusing Singer of libel and slander, and the zoo settled, but the damage had already been done: “San Franciscans seemed to be more put out over the shooting of a rare and beautiful animal,” SF Weekly wrote, than they were about the teens it had mauled.

The habits of mainstream journalism are easily exploited by people who know the business. Even here, I am practically compelled by conventions of balance to note that Sousa’s father told police that one of the injured teens admitted to him that he had been drunk and that he had yelled and waved at the animal. This information does important work, once introduced. The straightforward story of an institutional and regulatory failure—a zoo failing to implement recommended safety measures—becomes a melodrama about individuals behaving badly.

Speaking to SF Weekly‘s Joe Eskenazi, Singer bragged that getting journalists to use his narrative framing, and sometimes even his exact words, “is a rush that’s similar to sex and drugs and music.” Eskenazi wrote that it was “jarring” to hear such a boast from the son of a brainwashing expert; Singer pointed out that he used his mom’s lessons with good intentions, to help readers hear a different side of the story that they might not have considered. “I love my job,” Singer told the Richmond Confidential. “It’s like being an elected official without campaigning.” Some people who know Singer say he doesn’t lie, that he presents the truth as his clients see it, and that he appears to genuinely believe them. “Sam is extremely energetic and optimistic and always willing to believe the best of everyone,” a fellow consultant told Eskenazi.

“I love my job,” Singer told the Richmond Confidential. “It’s like being an elected official without campaigning.”

But that consultant added that Singer would still “throw a punch,” and that he’s the guy to hire when you want a fight. Case in point: Former business partner Larry Kamer remembers when he got a late-night call during a disagreement with Singer: “Larry, every time you start a fire for me, I’m gonna piss on it and put it out,” Singer said angrily before hanging up. The next morning, Kamer found a big wet spot on the beige carpet in their office—he had it removed, and rumors spread about Singer’s cutthroat tactics. It wasn’t until years later, when talking with Eskenazi, that Singer let everyone in on a little secret: “Decorum” would not allow him to urinate on a rug that he co-owned, he said, but it didn’t stop him from spilling a bottle of Heineken on it and letting everyone think what they thought. “This goes to my belief,” he said, a wide smile across his face, “that a good mindfuck is as good as the real thing.”

In recent years, Singer has shifted his focus to Oakland. Lately, he tweets almost daily about his disgust for the city’s progressive leaders. Speculating about why he has taken such an interest in Oakland has become a sort of dark parlor game among his antagonists.

City Councilmember Carroll Fife, whom Singer critiques often, believes he “has a bone to pick” after the Moms 4 Housing standoff in 2019, which she helped orchestrate with the squatting moms. At the time, Singer referred to them as “bullies” and “thieves,” and the real estate company he repped had them arrested and removed from the property in a predawn raid.

But the moms won in the realm of publicity: News outlets nationally wrote about their movement for affordable housing. Gov. Gavin Newsom helped negotiate a deal for a community land trust to buy the property, which became known as “Mom’s House,” and it was turned into a transitional home for homeless mothers. California lawmakers enacted reforms. “I think it was embarrassing for him,” said activist Nicole Deane, who worked with Fife. “He’s a professional who’s been doing this for decades,” added Fife, and he got beat by a group of Black women he’d described as criminals. “That can’t be a good feeling.”

Another theory is that Singer’s ties to the police turned his attention to Oakland. In 2020, Singer repped Anne Kirkpatrick after she was fired as the city’s police chief; she wound up prevailing in her wrongful termination lawsuit. In 2023, he also repped Oakland Police Chief LeRonne Armstrong while a federal monitor investigated Armstrong’s handling of a misconduct case. “He has a great reputation—he works hard for his clients,” Armstrong told me recently. With Singer at his side, Armstrong held a rally after newly elected Mayor Thao put him on administrative leave, and he accused the federal monitor of corruption. (A federal monitor has overseen Oakland’s police department for more than two decades to implement reforms that were mandated after a police brutality scandal.)

“I was surprised at the immediately aggressive tone that was taken in the public space,” said Hanson, chief of staff for Thao. Thao fired Armstrong the next month. Nothing else came of Armstrong’s accusation against the monitor.

Not long after that, efforts began to recall Thao and newly elected DA Price, who was also implementing reforms to roll back mass incarceration and hold police accountable. They weren’t the first progressive leaders to face backlash in Oakland: Mayor Jean Quan overcame a recall effort in 2012. Critics blamed them for high crime rates and business closures; Oakland, like many cities, saw a massive spike in shootings in 2020, before Thao or Price were elected; criminologists nationally connected the violence with the pandemic, and killings continued to climb after Thao and Price got to office—from 78 homicides in Oakland in 2019 to 126 homicides in 2023. Thao also faced attacks for Oakland’s budget problems.

But more than anything, these recalls were fueled by “the image of Oakland,” said political scientist Robert Stanley Oden, author of From Blacks to Brown and Beyond: The Struggle for Progressive Politics in Oakland. “The image of Oakland that lost three professional sports teams,” he continued, referring to the Warriors, the Raiders, and the A’s. And “the image of Oakland where you have crime occurring and an intractable homeless problem—people connect those two issues.” For decades before the pandemic, crime disproportionately affected low-income communities in Oakland’s flatlands, but now richer neighborhoods were seeing instability too. “The people who are being hurt the most by our failed policies are the poor,” said Scott, who leads the mayoral recall campaign. “And now most of the affluent want her gone, too.” A wealthy critic of Price, who asked not to be named, told me earlier this year that he’d dealt with two attempted break-ins at his house recently; his friend a block over was held at gunpoint. “For the first 30 years I lived here, it didn’t feel that way. I never had it in the neighborhood, in front of the house,” he said. “People are legitimately concerned.”

Journalist Ali Winston has pointed out that many landlords also oppose Thao because she helped enact an eviction moratorium while she was on the city council. This “set the wheels in motion for Thao’s recall virtually from her first days in office,” Winston wrote in August.

Thao and Price have framed the recalls as undemocratic movements led by real estate and hedge-fund investors. “This is nothing more than a power grab,” Price said in February. The recall campaigns have been mostly bankrolled by a single investor, Philip Dreyfuss, a hedge fund executive who lives in Piedmont, but the campaigns’ leaders dispute that their movement is undemocratic or right wing. Grisham, who heads the campaign against Price, says she’s organizing around grassroots frustrations with violence: She lost her 17-year-old son in a shooting outside their East Oakland home in 2010 as they were heading out to grab dinner at Burger King. I spoke with other mothers supporting the Price recall who are also grieving murdered children.

Singer has taken a hand in these elections, even if he’s not formally working for either campaign. His firm has donated $2,500 to the mayoral recall. And he is the spokesperson for the Oakland Police Officers’ Association, which held a press conference in August calling on Thao to resign because of rising crime. (Murders are down 33 percent in Oakland compared with last year, and violent crime is down 19 percent, according to the latest data.) “Every day you are in office, Oakland is less safe,” the association wrote to the mayor in a letter in August. “[I]t’s time to pack your bag and leave city hall.” (The association’s vice president told the Chronicle that this kind of protest was unusual—that he’d never seen the group ask a mayor to step down in his nearly quarter century as a cop.)

Singer has also done PR work for the Oakland NAACP, which similarly called on Thao to resign and accused Price of creating “a heyday” for criminals. (In 2023, a group of Oakland progressives complained to the national NAACP that Oakland’s branch had been “reverting to lies, fear-mongering and the ‘tough-on-crime’ rhetoric that has targeted African Americans throughout our entire history.” They urged the local branch to end ties with Singer.)

Singer has supported recalls in the past: In 2022, he went on a San Francisco podcast to promote the ouster of then-DA Chesa Boudin. He’s done PR work for at least a couple of Boudin’s opponents, including tech investors like Ron Conway and the ferociously antiprogressive Garry Tan. Conway is now a major funder of Oakland’s mayoral recall.

On X lately, Singer regularly tweets multiple times a day about Thao and Price, and his firm, Singer Associates, sometimes joins in. “America’s most crime-ridden city is run by America’s most incompetent mayor,” he wrote recently. In July, he emailed the Oaklandside requesting a correction to an article about an ethics investigation into the anti-Thao campaign. When the Oaklandside’s editor asked whether Singer was a campaign spokesperson, Singer did not answer directly. “I would like to connect you with OUST,” he wrote back, referring to the recall committee, “but your reporters have burned their bridges with the group and its leadership.” (“Part of what makes Singer compelling as a man-behind-the-scenes is that it’s never quite clear which strings he is pulling or how far his influence reaches,” the Richmond Confidential’s Bonnie Chan wrote. “Singer himself is rarely willing to disclose his part in his firm’s public relations victories.”) Complicating matters, Oakland progressives say the recall campaigns are organized in a way that makes it hard to track who’s involved. “It’s very challenging for the public and even people in this industry to understand all the connections,” said Hanson, Thao’s chief of staff. “It makes for murky public dialogue; you can sense there is coordination.”

Since Singer says he’s not working for the recall campaigns, the mayor’s office wonders whether he might be working for fossil fuel interests; Thao recently alleged that certain recallers may be motivated by a desire to ship coal through Oakland’s port, something she’s opposed in the past. (Singer did not respond to my request for comment.) In August, Singer’s firm donated to an independent expenditure committee that’s run by Greg McConnell, a lobbyist who works for Insight Terminal Solutions, one of the companies that wants to build an Oakland coal terminal. That committee spent money on online ads for Brenda Harbin-Forte, who is running for city attorney and is also a leader of the mayoral recall campaign.

Other progressives have questioned whether Singer might be working with Scott, the inflammatory recall leader. Singer regularly retweets Scott’s posts and shares his op-eds, and he’s written on X that Scott is “helping bring peace through positive, pragmatic, political change.” Singer didn’t respond to my question about this. When I asked Scott, he told me that Singer was probably just a fan. “I’m flattered,” he added.

Over the summer, more questions emerged about Singer’s involvement in Thao’s political predicament. In June, two days after the recall election was certified, the FBI raided her home early in the morning as part of an ongoing investigation. That same day, Singer was planning to host a press conference for an affordable housing measure; some reporters set to cover his event were among those who knew to be outside the mayor’s home around 6 a.m. for the raid. The coincidence made some Oakland politicos raise their eyebrows. Had Singer somehow known about the raid in advance? Did he tip off the reporters? “The timing of all this is troubling,” Thao said afterward. “I want to know how the TV cameras knew to show up on my sleepy residential street so early in the morning to capture footage of the raid. And I want to know why Fox News and Breitbart were so prepared to fan the flames, and to tell a story that they want to tell, to bend the facts to shape a narrative. I have a lot of questions and I will get answers. We all will get answers.” (Singer did not respond to my questions about this incident.)

“The mayor’s office is in crisis,” Singer told the local ABC affiliate after the raid. “I don’t see how she overcomes this, it’s likely that she will wind up having to resign.”

In October, Singer held a press conference at his office where 14 of the county’s police unions endorsed the recall of DA Price. Earlier that month, he also turned down my third request for an interview about his influence. “Thank you for letting me know that many people reference me, our agency, and our work, but I don’t have the time to devote right now to a profile. I am hardly a key figure, there are many people in Oakland and S.F. who have devoted countless hours walking, calling, donating and encouraging the public to vote for change,” he replied in an email.

About a week later, he sent me a press release from the Price recall campaign with no additional comment.

For decades, Americans have been sure that violence is rising, even when it isn’t. The Pew Research Center recently studied this phenomenon: In 23 of 27 Gallup polls since 1993, at least 60 percent of Americans said crime was higher in the United States than it had been a year earlier. But over that same period, FBI data showed that violent crime had actually dropped almost in half, and property crime had dropped even more. Americans today are much less likely to be a victim of violence than they were in 1993, but they sure as hell don’t feel that way.

Local news coverage, Pew found, is likely a big reason why. You’ve probably heard the journalism adage, “If it bleeds, it leads.” “Violent crime is much less common than property crime in the U.S., but Americans see local news about both types of crime with nearly the same frequency,” the researchers wrote, adding that many people also get their crime news on social media. “There’s a clear relationship between how much local crime news Americans consume and how concerned they are about their safety.” That’s not to knock crime reporters—I’m one of them. But it is to say that, sometimes, journalists make people believe that violence is more of a threat than it actually is.

Some academics have started thinking about crime waves as “moral panics,” or mass fear about something that’s been exaggerated. Moral panics can be about almost anything—historically, uproars over “witchcraft” would fall into this category, while a more recent example might be concerns about kids becoming violent because of video games. The key isn’t whether the threat exists, but whether it has been inflated and by whom and for what reason.

Stanley Cohen, the criminologist who named the phenomenon, identified the stages to a moral panic: Something is defined as a threat to society; the media amplifies the threat, treating it in a “stylized” fashion and drawing on prevailing popular prejudices; public anxiety is aroused and sharpened; “moral entrepreneurs” like activists or politicians or even savvy crisis communications specialists legitimize the panic by offering their own diagnoses and solutions. The panic dies down or results in change.

The first recorded crime wave moral panic was in 1744, when journalists in London, looking for something exciting to write about as news about foreign wars dwindled, started reporting on what they described as “swarms” of criminals, according to historian Richard Ward. Later in Victorian Britain, after reformers tried to roll back the use of public executions and floggings, journalists again led many readers to believe that crime had gone up, even though it hadn’t; lawmakers responded by enacting broader corporal punishment. Closer to home, the 1980s saw a moral panic about “crack babies,” notes social justice advocate Alec Karakatsanis, and in the ’90s a fear of teen “superpredators” helped President Bill Clinton pass the crime bill. “Crime waves” are frequently used to defend harsher punishments. Karakatsanis adds that “the ‘wave’…is often specifically manufactured by self-interested groups and complicit journalists precisely to have some political impact, whether it be the recall election of a DA whose policies they don’t like or blocking a bail reform bill or fear-mongering about slight shifts in budgets of police and prisons.”

“The ‘wave’…is often specifically manufactured by self-interested groups and complicit journalists precisely to have some political impact.”

More recently, crime panics in the United States have centered on retail theft. In 2021, a single shoplifting offense at a San Francisco Walgreens garnered 309 separate articles by local and national media over the course of a month. “This was during a public relations push by Walgreens, police unions, far-right media, and billionaire-funded DA recall activists to drive fear around ‘retail theft,’” Karakatsanis writes, referring to the recall of Chesa Boudin. Nationwide, the media’s obsession with shoplifting was so acute that the New York Times did a debunking in 2023, trying to answer why the issue had received so much attention, even though police data showed retail theft in most places was lower than it had been in years prior.

Violent crime has also been inflated. After the presidential debate in September, when Trump insisted that crime was “through the roof” despite FBI data to the contrary, the co-hosts of Fox & Friends defended him: “There is the numbers and there’s the reality,” Brian Kilmeadesaid, and Ainsley Earhardt added that “we’re all a little bit more scared than we used to be.” Media reports about violence tend to increase before elections: In 2022, the number of crime segments on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC grew enormously before the midterm vote; on Fox News, and likely on CNN and MSNBC, too, crime coverage plummeted afterward.

“Our common-sense understanding of crime waves is that crime rates are rapidly escalating and then falling off,” said sociologist Sacco, “but often the term is not used that way: It’s used to refer to an increase in public concern and media attention, rather than an increase in actual crime.” Moral panics, according to scholars Angela McRobbie and Sarah Thornton, are good for newsmakers: They “guarantee the kind of emotional involvement” that keeps readers or viewers coming back for more, and crime provides good visuals for broadcasters. In the political arena, the fearmongers can beat back any skepticism with a reliable rhetorical move. As Karakatsanis writes, “Anyone not reaffirming the narrative that crime by poor people is ‘out of control’ at any given moment—and anyone not responding to that problem with proposals of more prisons and police—doesn’t care about poor communities or communities of color.”

Oakland is a microcosm of these dynamics, and an example of the political consequences that can manifest when a mismatch grows between actual crime and people’s perceptions of it. Singer, recall committee leaders, and some local reporters have cast doubt on Oakland’s police department data showing that homicides and other offenses are falling rapidly in 2024. “Elected officials are still lying that crime is down,” Scott wrote to me in August. They have also linked business closures with crime in the city. When a Hilton hotel near Oakland’s airport announced in June that it was shutting down, some news reports speculated that crime was a cause. (“Unfortunately we are unable to comment,” a Hilton spokesperson told me when I asked whether this was true.)

Still, Singer and doom-loopers like him are effective at swaying public opinion because they are tapping into something real: Regardless of what the crime data says, people feel like their elected officials have let them down, because they are seeing things that make them uneasy—more clearly than ever before. “Even if you have the same number of unhoused people or mentally ill people or people visibly using drugs” as you did before the pandemic, “it feels like this overwhelming scary presence because there’s not hundreds of other people commuting to work, going to happy hour, getting a Starbucks,” said Boudin, San Francisco’s former DA, who was recalled in part because of similar doom-loop rhetoric. “That feeling has been very successfully manipulated by the likes of Sam Singer,” he said, to go after progressives. In San Francisco and Oakland, Republican pundits and even some mainstream Democrats have masterfully equated images of poverty and addiction with crime, arguing that public safety and liberal leadership are incompatible. Crime is “a canard,” but it’s also “the soft belly for progressives,” said Oden, the political scientist. “It’s creating a crisis around the individual who had nothing to do with the reason for the crisis to be what it is.”

Here is where Singer is so effective, whether the underlying story is a tiger jumping a low wall or a city navigating decades of municipal disinvestment. In his hands, the crisis becomes one of individuals behaving badly, a stylized drama of bullies and thieves and enabling corrupt politicians, not of low walls and institutional neglect.

In 2022, during the movement to oust Boudin, Singer spoke despairingly of “the tents, the defecation, the urination, just last week the vandalism of…a Michelin-starred restaurant.” He lamented that “San Francisco is a shadow of its former self, and that really has to do with the permissiveness of certain members of the board of supervisors as well as the district attorney’s office. They’ve created a situation where there are no consequences, and when there are no consequences of doing wrong, wrong just proliferates, and right now it’s out of hand.” Of course, people are living in tents because they can’t afford housing, and they’re defecating and urinating outside because they don’t have housing to defecate and urinate in, but in Singer’s narrative the problem of housing recedes—what low walls?—and the failures of the humans getting mauled are magnified. Singer then ties a bow around the package by invoking the vandalism at the restaurant, a nonsequitur that encourages his audience to see, in people living on the streets, not the effects of a housing crisis but the sources of crime. He offers an explanation (“permissiveness”) and a villain: progressive leaders, who now must be ousted.

In August he used a similar framework when he tweeted that Oakland had been on the “upswing” until Thao and Price were elected, but then its “future crumbled before its eyes…resulting in mayhem, violence, crime and chaos.”

“Even though we know for a fact that the district attorney is not the only factor in public safety, what Singer Associates is so effective in doing is making you forget that logic and lean into the villain narrative,” said Oakland Rising’s Manigo. “It’s like, ‘Who can we hang up there as the piñata to pound on for problems that are complex, that we all know are complex?” said DeBerry of the Prosecutors Alliance. “If crime was simple we would have solved it a long time ago; it’s not like the arrival of one new actor,” whether the mayor or the DA, “somehow caused the sky to fall.” Singer effectively “sets up the problem of Oakland as a city out of control, in a way that sets up the solution of new leadership that can pump the brakes and stop this careen into a doom loop,” said Pamela Mejia at the nonprofit Berkeley Media Studies Group.

The situation is exacerbated as more local papers fold due to financial problems. “No longer will a daily newspaper bear the name of Oakland,” SFGate wrote in 2016 after six Bay Area newspapers were consolidated into two publications. “In the absence of information, the lies or misinformation spreads,” Oden said. Meanwhile, social media has given politicos a bigger platform to create their own news: Scott, who leads the Thao recall campaign, hosts a video series called Gotham Oakland that regularly blasts progressives. “I do not call myself a journalist; I’m very open that I’m a propagandist—a truthful propagandist,” Scott told me.

All these factors add up. Mejia at the Berkeley Media Studies Group cites a phenomenon called the “mean world” syndrome: When people consume a lot of news about crime, they become convinced the world around them is a dangerous place. And when they see homelessness conflated with violence, they may buy into that idea, too. In September, Oakland business owners gathered with former police chief LeRonne Armstrong, who is now running for city council, to complain about progressive officials who planned to put a homeless shelter near the restaurants at Jack London Square. “As we watch the crime statistics go down, people’s perception of crime hasn’t changed,” Dorcia White, who owns Everett & Jones BBQ, told reporters at a press conference, explaining why she opposed placing a shelter so close to the business district. “We feed the homeless nightly, and as that population grows, so do a lot of problems.”

“We don’t have to fearmonger—we are scared!” Scott told me over the phone, yelling. “My lady doesn’t want to go down the street to her car without an escort—we’re scared! My neighbor was stabbed to death by a crazy homeless person—we’re scared!”

All the data in the world won’t change a simple fact: “If you don’t feel safe in a city,” Singer said in 2022, “then you’re not safe.” And with that, the moral entrepreneur had made his case.

Singer had little more to say when, after declining multiple interview requests, I sent him a long list of questions for this story. “Samantha, I have no role in the recall campaigns,” he said in an email. “It is troubling to see you and Mother Jones openly ignore the Blacks and Asians who started and run these political movements.”

It was a playbook described by Karakatsanis, nearly verbatim. In not reaffirming the narrative about crime, I was showing a lack of concern for communities of color. Singer went on: “Your questions to me demonstrate your discriminatory attitude toward people of color, the working class, the Nor Cal Carpenters Union and Oakland Police Officers Union.” For me to not focus on the nonwhite leadership of the recall movements “is disrespectful and discriminatory,” he concluded. “They are the leaders of The Revolution.”

On a Friday night in August, Mayor Thao sat on a stage in Oakland’s Chinatown during a “public safety town hall,” trying to dispel some of these bad vibes. Outside, a recall campaigner held a sign with the image of a sinking ship labeled “the ThaoTanic.” Inside, people who didn’t have a seat stood around the perimeter as Thao and her team listed some of the steps they’d taken to make people safer, from bringing back the Ceasefire gun violence prevention strategy (which Singer’s former client Armstrong, the ex-police chief, had effectively shelved) to installing more cameras on streets to identify car thieves. (Although they’re often conflated, property crime like car theft is not the same as violence. Such is the power of a moral panic that even Thao, one of its targets, seems to have accepted some of the doom-loop premise.)

Seated alongside her was the city’s new police chief, Floyd Mitchell. He took a question from the audience about people not trusting the city’s crime statistics, and tried to set the record straight. Though property crime data can take a while to update, sometimes leading to inaccuracies, he said data on violent crimes against people—think murders, rapes, aggravated assaults—“are 100 percent accurate.” “There’s absolutely no need for me or anyone in our organization to come up here and jeopardize their personal or professional integrity to try to give you inaccurate crime stats,” he said. “I understand people’s skepticism,” added Holly Joshi, who leads Oakland’s Department of Violence Prevention, but “as a city we weren’t questioning the stats when crime was up.”

Dispelling the bad vibes is an uphill battle. The Sam Singers of the world have money and time to fuel their narratives; they are at least offering an explanation for the visible deterioration of civic life, one that comports with centuries of folk wisdom about crime and criminals. Progressive politicians have not devoted the same energy to counter the doom. “There’s a market for content that’s salacious related to Oakland,” said Hanson, Thao’s chief of staff. “That’s a space where the city is perhaps less nimble, and [it] does not dedicate any public resources to combat that.” A journalist at the Bay Area News Group told me he reached out to the Oakland Police Department more than 10 times while reporting a story about Oakland crime, but nobody responded, so he turned instead to the police union, repped by Singer: The resulting story, which published in September, said Oakland’s violent crime rates had surged but did not mention 2024 data, which shows they’ve been dropping. Singer himself has been quoted in other articles about specific Oakland crime incidents, when it would more commonly be the police department’s job to comment. “There are PR firms that are progressive, and they cost money,” said the attorney Walter Riley, who helps lead a group countering the recalls. “Our group does not have that, so we are at a disadvantage in that sense. We are not gonna get the coverage of Fox News or even the Chronicle newspaper.”

It’s also more difficult to convey nuanced messages about crime. Scapegoating a villain is more emotionally satisfying than dissecting the societal structures that perpetuate lawlessness—things like racism, poverty, unaffordable housing, and unemployment that have no easy answers. Who wants to stare at a wall, to really examine all its holes and dimensions, when you could instead be morbidly entertained by a tiger hunting down miscreant teens?

Thao recently brought on PR specialists from the Worker Agency to help her fight the recall, but it may be too little too late: According to Oakland’s Chamber of Commerce, a majority of respondents in a recent poll said “current progressive policies are not benefiting the city,” and more than half indicated they would vote the mayor out; nearly half in another poll by a pro-recall group said they didn’t think Price was doing a good job. “Progressives have the power to defeat anything because there’s more people—the population they represent is larger,” said political scientist Oden. “But they can never organize them enough.”

Who wants to stare at a wall, to really examine all its holes and dimensions, when you could instead be morbidly entertained by a tiger hunting down miscreant teens?

On a Saturday in August, I watched some of them try to prove him wrong. Respect Our Vote, No Recalls, a coalition of residents, activists, nonprofits, and Democratic clubs, called a community meeting inside At Thy Word Ministries Church in East Oakland to talk through their communication strategies. “It’s really true that democracy is in the balance,” Pastor B.K. Woodson, one of the group’s leaders, said from a podium. “We want you to take the information you get here today and spread it around: In every conversation you have, ask: Are you registered? Will you be voting?”

A woman in the audience raised her hand and asked about the media: She felt “bombarded” by negative news about Oakland and wondered how to respond. “Call up those MFers,” a woman in a sunhat urged her, referring to journalists. “Tell the real story.” Another woman in a flannel shirt got emotional while talking about her effort to fact-check the bad information online. “I don’t wanna be the only one on Nextdoor fighting these assholes!” she said, starting to cry.

Sam Singer’s name never came up, but the meeting was unmistakably a rally against not just his message but his method, the emphasis on wayward individuals and not the low walls leaving Oaklanders vulnerable. In the end, the progressive leaders urged each other to get offline, to stop all the doom-scrolling and go meet their neighbors. “To get the real information, you need to go to the communities that are in the trenches with their sleeves up,” said Stewart Chen, president of the Oakland Chinatown Improvement Council. “Have these discussions outside these rooms,” said Turner, the Democratic delegate.

“You are our hope,” said Woodson, calling the meeting to an end. “Go talk to people.”

As H5N1 bird flu continues to spread wildly among California dairy herds and farmworkers, federal health officials on Thursday offered some relatively good news about Missouri: The wily avian influenza virus does not appear to have spread from the state's sole human case, which otherwise remains a mystery.

On September 6, the Missouri Health department announced that a person with underlying health conditions tested positive for bird flu, and later testing indicated that it was an H5N1 strain related to the one currently circulating among US dairy cows. But, state and federal health officials were—and still are—stumped as to how that person became infected. The person had no known contact with infected animals and no contact with any obviously suspect animal products. No dairy herds in Missouri have tested positive, and no poultry farms had reported recent outbreaks, either. To date, all other human cases of H5N1 have been among farmworkers who had contact with H5N1-infected animals.

But aside from the puzzle, attention turned to the possibility that the unexplained Missouri case had passed on the infection to those around them. A household contact had symptoms at the same time as the person—aka the index case—and at least six health care workers developed illnesses after interacting with the person. One of the six had tested negative for bird flu around the time of their illness, but questions remained about the other five.

© Getty | Matthew Ludak

When J. Vasquez was incarcerated at Salinas Valley State Prison in California, he worked as a porter—sweeping, mopping, and taking out the trash. It paid less than 15 cents per hour and, as the “third watch” porter, he worked from 2 to 9 p.m. The timing of his shift often coincided with prison programming, which was a source of continual frustration for Vasquez. He had entered prison at 19 and was looking to “take accountability for [his] life.” But he was not allowed to take time off his job to attend classes. When a group of crime survivors came to the prison to speak with incarcerated people, Vasquez told me, “I thought about just putting down that broom and going anyways.” But he feared that if he refused to work, it could result in a disciplinary violation, which would eventually appear on his parole application.

California’s penal code requires that most incarcerated people work while they are in prison, and if they refuse to do so, they can be disciplined—ranging from losing access to phone calls to being placed in solitary confinement. This is because California’s state constitution has one caveat to its ban on involuntary servitude: It is allowed “to punish crime.” Proposition 6 will give California voters an opportunity to decide whether to remove this exception from the constitution.

For advocates of Prop 6, the exception in the state constitution is a clear, and troubling, remnant of slavery. “The practice of involuntary servitude is just another name for slavery in our California prisons and jails,” Carmen-Nicole Cox, an attorney at ACLU California Action, told Mother Jones.

“The practice of involuntary servitude is just another name for slavery in our California prisons and jails.”

But the movement to abolish involuntary servitude has not been as straightforward as one might imagine in California, and advocates face an uphill battle. A statewide poll conducted in early September found that 50 percent of voters said they would vote against the proposition, while 46 percent would vote for it.

Of the 95,600 people incarcerated in state prisons in California, around 65,000 work. This reflects the national trend: A 2022 ACLU report estimated that two out of every three people incarcerated in state and federal prisons work. In California, the majority of jobs involve the day-to-day operations of prisons: preparing food, doing laundry, or completing janitorial duties. Some jobs are unpaid, but most pay between 8 and 37 cents per hour.

Around 7,000 incarcerated people work manufacturing and service jobs—such as making license plates, processing eggs, and fabricating dentures—through the California Prison Industry Authority. Those jobs are coveted because they pay more—their range is between 35 cents and $1 per hour. Around 1,600 people work in conservation camps, where they respond to fires and other natural disasters. They’re paid between $1.45 to $3.90 per day and paid an extra $1 per hour for emergency firefighting.

Currently, at least 15 states have constitutions that allow involuntary servitude as punishment for crime. Lawmakers around the country have moved to ban forced prison labor by amending their state constitutions. In 2022, voters approved amendments in Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont—joining Colorado, Utah, and Nebraska.

In 2020, Sydney Kamlager-Dove, then a California Assembly member, introduced an early version of a ban on forced prison labor. But it failed to pass the state Senate after the California Department of Finance opposed it, writing in a report that given the broad language of the amendment, its financial impacts were largely unknown. The report warned that it would cost taxpayers around $1.6 billion to pay incarcerated workers California’s minimum wage, which was $15.50 in 2023. Plus, the report said, the measure could make the state vulnerable to potential litigation from incarcerated people. In Colorado, for instance, incarcerated people sued in 2022 because they still were forced to work despite a constitutional amendment banning involuntary servitude in prisons.

The report also pointed out the broad definition of involuntary servitude. Judges can sentence someone to community service instead of a fine or jail time—because that work is unpaid, it might also be considered involuntary servitude.

Democratic state Sen. Steve Glazer voted alongside five Republicans against the measure. After it failed, Glazer said in a statement that the issue of forced prison labor was better suited for the legislature to take up. He argued that unilaterally banning the work requirement would “undermine our rehabilitation programs” and “make prisons more difficult to manage safely.”

This time around, a companion bill—intended to address concerns about prisoner pay—would allow the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to set wages for incarcerated workers if a constitutional amendment passes.

In January, Assembly Member Lori Wilson brought back the measure, which was included in a package of bills recommended by the California Legislative Black Caucus as part of reparations for the descendants of enslaved Americans.

Although the current version of the ballot measure easily moved through both the state Assembly and Senate—with the support of Glazer—many of the same concerns persisted. Glazer recently told Capital Public Radio that he is still worried about “unintended consequences” for prisons. There has been speculation that if incarcerated people refuse to work in laundry and kitchen positions, prisons will find it difficult to function. Glazer told the radio station that he had been assured that the state could still compel people to do “chores.”

In particular, financial concerns linger. Even if incarcerated people are not paid minimum wage, the amendment may still result in higher prison operation costs. A summary prepared by the attorney general’s office cautioned that prisons might have to find “other ways of encouraging working” if incarcerated people are not disciplined for refusing to do so. This might include raising pay or offering “time credits” off a prison sentence.

Advocates say these concerns reflect a misunderstanding of life inside prison. Vasquez, who is now a policy and legal services manager at Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice, said incarcerated people frequently want to work, even if only to get out of their cells. There also are some “fringe benefits” to working, he explained. As a porter, Vasquez was able to get some spare cleaning supplies, and extra food might be available for those who work in the kitchen. And given that there are positions available for only about two-thirds of incarcerated people, there are sometimes waiting lists for jobs.

Moreover, advocates say it is misguided to calculate the cost benefit of Prop 6 only in terms of the burden on taxpayers. Brandon Sturdivant, the campaign manager for Prop 6, says eliminating forced prison labor will give incarcerated people the opportunity to pursue rehabilitation and better prepare themselves to return to their communities. Sturdivant said his father spent 12 years in prison, where he spent time making license plates instead of “getting the tools he needed to come out and be a father and a pillar of his community.”

Proponents of Prop 6 also point out that education and rehabilitation programs have been found to reduce recidivism. And this has its own economic benefit—it now costs $132,860 per year to incarcerate someone in California. To Sturdivant, the biggest hurdle in passing Prop 6 is reaching and educating voters, which the coalition of organizations supporting the ballot initiative has been attempting to address through phone banks. When talking to voters, they try to dispel misconceptions and frame the issue in personal, humanitarian terms. Esteban Núñez, a formerly incarcerated consultant and strategist, said that fundamentally, Prop 6 presents voters with a “moral issue” and a chance to “restore dignity to those inside.”

In August, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, in his working-man’s clothes—aviators, jeans, and a trucker hat—starred in a video where he carted people’s possessions out of a homeless encampment near a Los Angeles highway.

On any given night in 2023, more than 650,000 people in the US experienced homelessness, with almost 400,000 unsheltered—though that figure may be an underestimate. Research by the federal Government Accountability Office found that every $100 rise in median monthly rent brings about a 9 percent increase in homelessness—notable as rent costs have climbed by 25 percent nationally since 2020, according to CNBC.

Newsom’s photo op followed his July order calling for the clearing of encampments on public property, and came alongside a threat to withhold state funding from cities and counties that failed to meet his requirements, much to the ire of local officials like Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass. On July 25, the day of the order, the governor posted on X: “No more excuses. We’ve provided the time. We’ve provided the funds. Now it’s time for locals to do their job.”

Earlier this month, Newsom approved more than $130 million in funding for 18 cities, including over $12 million to Riverside, to “sweep” encampments. According to the governor, the goal is to support “efforts to get people out of encampments and connected with care and housing across the state.”

A statewide audit released in April tracked investment during Newsom’s first five years as governor, from 2019 to 2023, and found that California spent roughly $24 billion in that span to address housing and homelessness. At his inaugural address in January 2019, Newsom vowed to “launch a Marshall Plan for affordable housing and lift up the fight against homelessness,” promising to push for the development of 3.5 million housing units across the state by 2025.

According to CalMatters, his administration has since backtracked numerous times, calling in 2022 for cities to have planned a combined 2.5 million homes by 2030. The state still has about one-third of the country’s unhoused people, more than half of whom, in many cities—like San Francisco—are without any kind of shelter.

In Orange County, many homeless advocates denounced Newsom’s strategy as criminalizing life without shelter rather than driving the construction of affordable homes.

“All things like this do is just shuffle the chairs on the deck of the Titanic,” said David Gillanders, the executive director of Pathways of Hope, an Orange County organization that provides shelters and other support with housing. “If you uproot a person who’s living in an encampment, they’re just going to find another place to go if you’re not offering them an appropriate sort of accommodation.”

Gillanders cites California first responders who moved to—and started commuting from—Idaho, or even further afield. Kyle Conforti, an Orange County firefighter who lives in the suburbs of Nashville, Tennessee, told the Guardian that the rise in cost of living “outpaces my raises and income. So we finally just ran the numbers and figured out it would be cheaper to live out of state and have me commute back.”

According to a 2024 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, California has the highest housing costs in the nation. At an average of some $2,500 a month, it takes an hourly wage of almost $50 to afford a two-bedroom residence without being “cost-burdened,” or spending more than 30 percent of income. Another study released this year by the California Housing Partnership found even higher average rents in Orange County: just under $2,800, meaning renters would need to earn about $54 per hour.

“We are going to make them so uncomfortable on the streets of San Francisco that they have to take our offer.”

But not everyone in California is opposed to Newsom’s focus on encampments. San Francisco is among the largest cities to double down on a confrontational policy of eliminating encampments through police enforcement. In August, the city’s mayor, London Breed, strengthened one of its three separate programs to push unhoused people out of the city by offering one-way bus tickets before shelter or other services.

Responding to Newsom’s order in July, Breed said, “We have offered people shelter and space, and many people are declining…But we are going to make them so uncomfortable on the streets of San Francisco that they have to take our offer.”

Other city councils have similarly prioritized police raids of encampments. From 2006 to 2019, the National Homelessness Law Center found, the number of city-wide bans on camping and loitering doubled—and bans on living in vehicles tripled. Newport Beach, another wealthy Orange County municipality, unanimously voted to intensify anti-camping law enforcement by recruiting more officers for its police “Quality of Life” teams, which issue citations for camping and related violations, withdrew funding for a mobile mental health response team, and, according to the Los Angeles Times, is considering the hire of a full-time city attorney dedicated strictly to prosecuting anti-camping laws.

In early October, the city’s ordinance banning camping on public property went into effect, and within hours, all encampments were cleared by public works crews and police. The ordinance does not require Newport Beach to offer services to those who have been forced out.

But the most recent arguments over homelessness began in the lead-up to a June Supreme Court ruling, City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, that overturned a 2018 lower court decision banning local laws against camping on public property if cities didn’t also provide adequate temporary shelter.

In that case, amicus briefs from various parties—including Newsom—were filed to the Supreme Court. One included petitions from 10 California cities, and Orange County, about the consequences of Martin v. Boise, the lower court’s ruling. Orange County called it “financially unsustainable,” citing a 2019 settlement payment of more than $2 million and a potentially “impractical” requirement to provide one shelter bed per person unhoused. The county’s budget for the 2022-2023 fiscal year was $8.8 billion.

Garden Grove, another of Orange County’s largest cities, wrote, “The further impacts of Martin include an increase in homeless individuals by 49% since 2017, an increase in petty crime and theft, and an increase in overdose calls from Fentanyl and other deadly narcotics.”

The Garden Grove comments came from a declaration by Sergeant Jeffrey Brown, the head of its police department’s “Special Resource Team” on homelessness. Brown referred to 2021 numbers demonstrating that less than one percent of homeless people were accepting referrals to shelter or inpatient mental health facilities, and wrote, “As it relates to encampments, the Martin decision has effectively disabled” local police “from mitigating encampment growth and homeless activity on public streets, sidewalks, and rights of way.”

“Now part of their housing solution would be to house them in jails.”

Neither the Garden Grove Police Department nor Brown responded to a request for comment.

Asked why people experiencing homelessness in nearby Newport Beach were turning down shelter bed offers, Natalie Basmaciyan, the city’s homeless services manager, said, “We tend to have a slightly older unhoused population in our region, and they’ve gone through shelters in the ’80s and ’90s and even in the ’00s that were not well-managed. They didn’t have good facilities…You know, here’s a sack lunch. You need to leave for the day. You have to queue up at 5pm and hope you get a bed again.”

“We don’t do that,” said Basmaciyan. “Once you’re assigned a bed and you’re in our program, you are here until you get housed.”

Vox found that other reasons many people avoid shelters range from having to give up pets and personal belongings to having to leave a partner at a gender-segregated facility.

Even adequate shelters present problems absent a system to move people to permanent supportive housing. “We have people that have been in a temporary shelter for three years,” Joe Stapleton, the mayor pro tem of Newport Beach, admitted.

According to CalMatters, homeless shelters themselves often pose health and safety risks; the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California found raw sewage flowing from porta-potties, broken showers, rodent and maggot infestations, a lack of wintertime heating, and flooding during storms. The ACLU also uncovered accounts of unchecked theft, sexual abuse, and violence. Despite California law requiring shelter inspections and repairs, CalMatters found little to no evidence of accountability, with just four of the state’s 478 cities filing mandatory shelter reports—apparently without consequence.

For those who turn down shelters, Newport Beach’s municipal code provides a list of penalties enforced via civil or criminal citation, which both escalate with repeat offenses and accrue interest and late fees.

According to Stapleton, applying those penalties “is a last resort,” as is calling police.

“This is where the system has failed, where it’s like, how many times is somebody going to remain on the streets, refusing all the services and everything that we’re providing, to a point where they’re going to continue to sleep in front of a business. I don’t think we have the solution. I don’t think anybody has a solution,” said Stapleton.

Cesar Covarrubias, executive director of the Kennedy Commission, an Orange County nonprofit that works to increase production of homes for lower-income residents, described the penalty structure as a trap that unhoused people are forced into.

“Individuals who are homeless get citations,” said Covarrubias, and if those go unpaid, “then there’s warrants that are issued against them.” Most people cited “are never going to be able to pay for those,” he said, “and it just continues to be a cycle where now part of their housing solution would be to house them in jails.”

Covarrubias suggested that “more affordable housing needs to happen through regional and local partnerships with cities,” using publicly owned lands and “local, regional, and state funding…to really create more housing that is affordable.” But the focus on clearing encampments, he said—especially following the Grants Pass decision and Newsom’s order— has hindered progress.

State and local authorities “are really going to stifle this collaboration of addressing housing and homelessness regionally, because there is just no incentive for them to do so,” Covarrubias said. “Now they’re going back to what they traditionally did, which was more enforcement [and] criminalization of homelessness.”

Cities are also divided on housing construction. According to Covarrubias, many municipalities are failing to satisfy guidelines set by the Regional Housing Needs Assessment, a California mandate that decides how much housing each city requires to meet affordability standards. The assessment is a planning tool, he said, that in theory discourages landlords and developers from building only market-rate housing.