Cracking the recipe for perfect plant-based eggs

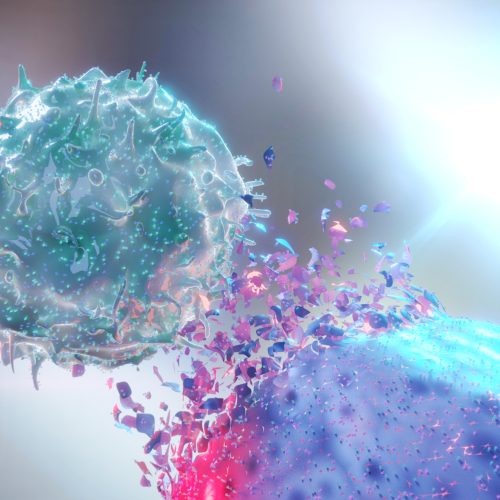

An egg is an amazing thing, culinarily speaking: delicious, nutritious, and versatile. Americans eat nearly 100 billion of them every year, almost 300 per person. But eggs, while greener than other animal food sources, have a bigger environmental footprint than almost any plant food—and industrial egg production raises significant animal welfare issues.

So food scientists, and a few companies, are trying hard to come up with ever-better plant-based egg substitutes. “We’re trying to reverse-engineer an egg,” says David Julian McClements, a food scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

That’s not easy, because real eggs play so many roles in the kitchen. You can use beaten eggs to bind breadcrumbs in a coating, or to hold together meatballs; you can use them to emulsify oil and water into mayonnaise, scramble them into an omelet or whip them to loft a meringue or angel food cake. An all-purpose egg substitute must do all those things acceptably well, while also yielding the familiar texture and—perhaps—flavor of real eggs.

© Nico De Pasquale Photography via Getty