Nearby star cluster houses unusually large black hole

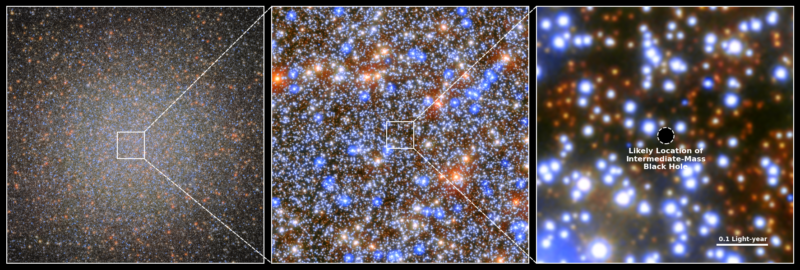

Enlarge / From left to right, zooming in from the globular cluster to the site of its black hole. (credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle)

Supermassive black holes appear to reside at the center of every galaxy and to have done so since galaxies formed early in the history of the Universe. Currently, however, we can't entirely explain their existence, since it's difficult to understand how they could grow quickly enough to reach the cutoff for supermassive as quickly as they did.

A possible bit of evidence was recently found by using about 20 years of data from the Hubble Space Telescope. The data comes from a globular cluster of stars that's thought to be the remains of a dwarf galaxy and shows that a group of stars near the cluster's core are moving so fast that they should have been ejected from it entirely. That implies that something massive is keeping them there, which the researchers argue is a rare intermediate-mass black hole, weighing in at over 8,000 times the mass of the Sun.

Moving fast

The fast-moving stars reside in Omega Centauri, the largest globular cluster in the Milky Way. With an estimated 10 million stars, it's a crowded environment, but observations are aided by its relative proximity, at "only" 17,000 light-years away. Those observations have been hinting that there might be a central black hole within the globular cluster, but the evidence has not been decisive.