Scales helped reptiles conquer the land—when did they first evolve?

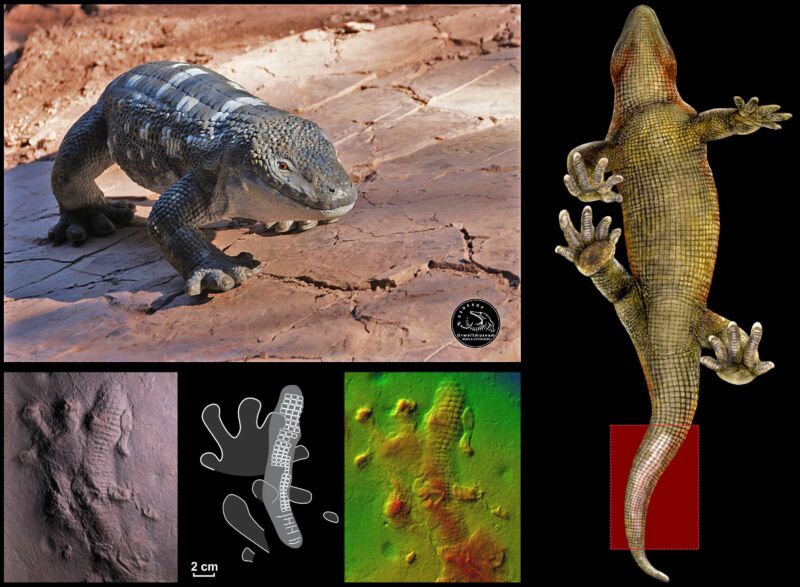

Enlarge / Upper left: a reconstruction of Diadcetes Below: false color images of its foot and tail prints. Right: the section of the tail that left the print. (credit: Voigt et. al./Urweltmuseum GEOSKOP.)

Their feet left copious traces in muddy Permian floodplains, leaving tracks scattered across ancient sediments. But in one slab of such trackways, scientists uncovered something more: the trace of an animal’s tail as it dragged across the ground. Strikingly, these tail prints come complete with scale impressions—at 300 million years old, they’re among the earliest scale impressions we have.

This may seem small, but it shows us that some of the hardened skin structures necessary for our ancestors to survive on land had evolved much earlier than previously suspected. A paper published in Biology Letters this past May describes this discovery in detail.

A rare find

The particular slab holding these traces was discovered in 2020 at the Piaskowiec Czerwony quarry in Poland. Mining had stopped to enable paleontologists to search the red sandstone rocks for fossils. Gabriela Calábková described climbing upon “a huge pile of rubble” only to discover a sizable slab of fossil tracks at the very top. There, among one set of footprints, was something new.