‘The Office’ Christmas Storybook Has Arrived — And It’s Already a No. 1 Bestseller on Amazon

Jeff VanderMeer insists that he does not predict the future. Yet mere weeks before his new novel, Absolution, hit shelves, Hurricane Helene tore through the part of Florida where he lives, sharing an uncanny likeness to the fictional hurricane in his book. Of course, there’s a difference between art and reality. The through line between the storms is the climate crisis that inspired VanderMeer to write the trilogy of books that made him a household name a decade ago.

Absolution is the latest and last installment in the lush, eerie series covering an unknown biological phenomenon known as Area X, located in VanderMeer’s home state of Florida in the real place known as the Forgotten Coast. The original trio of books covers the area and its tendency to affect living creatures and create bizarre refractions of life within its confines. The series, called the Southern Reach trilogy, garnered enormous praise, a legion of fans, and a movie adaptation. For the record, VanderMeer told me he found Hollywood “frustrating” because “they stripped out all the environmental stuff.” But he did enjoy the movie’s surreal ending.

“We get displaced. We have to be resilient. We have to form a new narrative.”

A decade later, Absolution marks the conclusion of a weird and wonderful journey involving an assortment of biological abnormalities and government secrets. In the meantime, it seems as if the unusual world that VanderMeer wrote about and the one that we live in today are growing closer and closer. Our warmer world is not just more volatile in terms of natural disasters, like Helene and Milton, but it is also becoming a large-scale petri-dish for new diseases, the type of biological mixing and matching that VanderMeer’s books are known for—albeit on a much smaller scale.

In VanderMeer’s fiction, the mirror world of Area X produced strange, haunting results like a character’s transformation into a whale-like creature covered in eyes, or a murderous bear with a human voice. But for VanderMeer, climate change is the scariest thing of all.

I spoke with him just as he was returning to his home in Tallahassee after evacuating from Hurricane Helene. This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

What is it like being a climate and science fiction writer right now?

I guess it feels like kind of a privilege to be able to talk about this stuff, that the novels have reached enough readers and had enough of an impact that anyone cares what I have to say.

It’s also true that I’m right now in Florida, at the epicenter of a lot of extreme weather events. And so that creates a weird echoing effect. For example, I was fleeing Hurricane Helene up to Greenville, South Carolina, unsure if that was even the right thing to do. And then also asked by the New York Times to write a piece about fleeing the hurricane. So there’s all this real-world consequence.

You’re getting me at the end of fleeing a hurricane, writing about it, coming back to Tallahassee, seeing the consequences of extreme weather because of warming waters because of climate crisis, and feeling both thankful that I can kind of capture a feeling people have here about these events and write about it, but also kind of caught up in it as well.

That sounds pretty jarring.

You can get in loops too, where you don’t really adapt to the situation and you’re just doing the same talking points which, relevant to your question, is something I worry about. You know, where [people on the internet] were saying, “Well, why did people even build in Asheville?” it was this weird disconnect. And it’s like, “Well, because they didn’t expect there’d be these mega-storms that would still have a huge effect, hundreds of miles inland.”

People in the aftermath of destruction seem to want to try to form their own narratives about what’s happening, and I’m sure you are someone who see this clearly, being in the epicenter, but also being someone who works in fiction.

It’s definitely something that I write about in my fiction: the idea of character agency in the face of systemic or system-wide events, whether they’re human systems or systems in the natural world. Especially in Western fiction, we have this idea of rugged individualism, right? And by the end of the narrative, things will have gone back to normal, because something’s been solved.

That’s not really what happens in the real world. We get displaced. We have to be resilient. We have to form a new narrative. We’re not always the same person we were before, you know, especially with regard to the climate crisis. And so I try to capture that. There’s a hurricane in Absolution that comes up suddenly in the middle of all these other events. And I really wanted to capture how a hurricane these days can seem like an uncanny event, even to those of us who are familiar with them.

“People think the climate crisis is on the horizon…But more and more, we’re all being affected by it.”

Helene, to be candid, scared the crap out of me when I saw it coming to Tallahassee with 150 mile per hour winds. A lot of people decamped from Tallahassee up into North Carolina, and then were completely trapped. People think the climate crisis is on the horizon, and if they think that it’s because they haven’t been affected by it yet. But more and more, we’re all being affected by it.

In this book, Absolution, and in all the books, there are these in-group, out-group dynamics, and I’m just wondering, why is that something that you’re really interested in exploring narratively?

I’m trying to explore the psychological reality of being in these situations. I’m not trying to extrapolate, I’m not trying to predict. I’m simply trying to show what people are like facing these kinds of choices. Because, you know, people talk a lot about the landscapes and uncanny events, but they’re all filtered through a particular character point of view. And I often ask myself, is this person open to what’s happening or are they closed? Are they in denial? Are they understanding to some degree? Are they trying to form connections or are they disconnected and alienated? These are some of the issues that we find in modern times.

How do you talk to scientists? Because this series is very science-based, but the emotional resonance of why people are drawn to science is something that comes through a lot.

My dad is a research chemist and entomologist who’s always headed up or been part of some lab, usually like fire ants and other invasive species. And so I grew up around these kinds of places. My mom was a biological illustrator for many years, and so that also brought a kind of a scientific element to her art. And between those two kinds of locations, I got to see the real human side of science.

I think that actually really helps, along with going on actual scientific expeditions with my dad to Fiji as a kid, it’s just kind of intrinsically in you at that point that you have an understanding of science. I was really quite lucky in that regard.

What was helpful to you to get this book across the finish line?

One thing that was helpful is that there’s actually a lot of humor in it. I don’t like to write books that are monotone. Even in Annihilation, in the earlier books, there’s some sly humor going on. Here, I think it’s a little more overt in some of the relationships and some of what the secret agency is doing that’s so absurd. And then in the last section, especially with this very dysfunctional, almost tech bro-esque personality that’s in this expedition. It’s kind of unintentionally funny. That’s something that anchors me, because it gives me pleasure to write, along with the uncanny stuff.

What’s the role of fiction at this point in the climate crisis?

I think one thing I don’t want the books to do when they skirt the edge of “prediction” is to be unrealistic. I get asked a question a lot, “Where’s the hope in your books?” or things like that. And it’s like, I don’t want the hope, I want the analysis. And I don’t want the faux analysis where we’re doing like carbon offsets that are meaningless. I don’t want to put that in my book as something that’s viable.

I think that what fiction adds is—it’s kind of like: What do you get from religion versus science, or what do you get from philosophy rather than science? Fiction is not science, but it can give you this immersive three-dimensional reality of what it’s like to be in a situation, and it can bring your imagination to it in such a way that it really lives in your body to some degree.

And so I think that’s why the thing that makes me most happy is having people come up to me and say that Annihilation was one reason they became a marine biologist or went into environmental science, that there was something about the character of the biologists in that book that was compelling to them. That to me, is what fiction can provide.

For a personal tribute to Don Barlett, read “‘Hello, I’m Don Barlett and I Liked Your Story’” from our CEO emeritus, Robert Rosenthal.

It’s not often that an obituary truly surprises you, but the other day it happened to me in the best possible way. The person who passed wasn’t a relative, friend, or close colleague. But he did play a key role at one point in my life, by showing me what journalism can do—and often fails to.

Barlett was half of Barlett and Steele, a reporting duo as significant as Woodward and Bernstein, but in a very different way. When they worked for the Philadelphia Inquirer, they embodied the shoeleather investigative reporting that newspapers once nurtured. My colleague Robert Rosenthal, who was their mentee and friend at the Inquirer, has some moving (and funny!) recollections of the duo here.

But I wanted to zoom out a little, because the kind of reporting Barlett and Steele did is special, valuable, and endangered, and also because of the thing that surprised me in that obit: its last line. “Donations in his name may be made to the Center for Investigative Reporting, Box 584, San Francisco, Calif. 94104.” That’s us! The Center for Investigative Reporting is Mother Jones’ parent organization, and we are a bit of a Noah’s Ark for this kind of endangered journalism.

I was floored when I saw that line, and here’s why. In 1991, I was just out of journalism school, in the middle of a recession and the run-up to a presidential campaign, when Barlett and Steele published a series called America: What Went Wrong? It was a deep dive into the rising income inequality that had come to dominate the US economy.

The pair worked on the series (and subsequent book) for many months, and the book opens with a series of thank-yous that feel like a time capsule: “Lela Young, in the public reading room of the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington.” But what comes next could have been written yesterday: There are all these pundits on TV talking about how the economy isn’t so bad and everything will be fine, Barlett and Steele note. But then why does it not feel fine to so many people? Here we see a giant graphic that looks exactly like what you would make on your Apple Macintosh in 1991 (you can find it on page ix in the Google Books version). It shows that the top 4 percent of Americans make as much (just in wages, not counting investment income) as the bottom 51 percent.

Perhaps, Barlett and Steele wrote, it’s no wonder that “the stories you read in newspapers and magazines seem disconnected from your personal situation.” Those stories don’t talk about the factories and workplaces being shuttered, about millions of workers going from earning $15 an hour to $7 an hour. “For the first time in this century, members of a generation entering adulthood”—GenX—“will find it impossible to achieve a better lifestyle than their parents. Most will be unable even to match their parents’ middle-class status.”

These Americans, they write, look at the economy from the bottom up. “Those in charge, on the other hand, are on the top looking down. They see things differently. Call it the view from Washington and Wall Street.” Those folks include corporate execs, Republicans—led by Reagan and George H.W. Bush—who pushed through tax giveaways, trade deals, and deregulation, but also Democrats who went along with it.

Imagine the economy like a hockey game, Barlett and Steele continue, “a sport renowned for its physical violence.” Now imagine what the game would look like if you took away the rules and referees. “That, in essence, is what is happening to the American economy. Someone changed the rules. And there is no referee. Which means there is no one looking after the interests of the middle class. They are the forgotten Americans.”

It’s incredibly striking rereading, 33 years later, how accurately Barlett and Steele captured the dynamic that still defines our economy—and our politics. It’s also striking to remember how few mainstream journalists were doing that kind of reporting, and how many fewer do it now.

When I started in journalism, smack in the middle of that early-’90s recession, there were still a lot of investigative reporters in newsrooms, and they did great work, but there was something that defined most of those stories: They were about exposing people breaking the rules. Politicians stealing from the public purse. Construction workers catching naps on the taxpayer’s dime. Reporters exposed illegal acts, not ones that were merely unfair or inequitable. And there was a reason for that: Mainstream newsrooms had positioned themselves as carefully neutral; value judgments had no place in their work. But the mission of investigative reporting, inherently, is about showing the contrast between how things are and how they should be—it’s about exposing wrongs. Every investigative reporter since Ida B. Wells shone a spotlight on lynching has been animated by this.

Defining “wrong” as “rulebreaking” was a way to avoid making a value judgment—but it meant that a lot of important stories were not told. Stories about systems, especially, such as the growing inequality in the US economy.

That’s what made Barlett and Steele’s reporting so unique, and so powerful. What happened to incomes in America was wrong, it was right there in the book title. Not because it broke any laws (the point was that it was all perfectly legal!) but because it was unfair.

Seeing that journalism could do that—could expose not just lawbreaking, but systemic injustice—was an aha moment for cub reporter me. That’s the kind of work I wanted to be doing, and apparently there were jobs for people to do it.

Little did I know that most of those jobs were about to disappear. Investigative reporting is expensive, and the corporations and hedge fund investors who were buying up America’s newspapers had no intention of paying for it—or, ultimately, for any newsroom jobs. Since Barlett and Steele wrote their series, nearly half of America’s journalism jobs have disappeared (a loss rate faster than coal mining), and most of the rest are on borrowed time. There are very few journalists who can take the time to dig deep on a big issue, especially one as hard to get your arms around as income inequality.

And the idea of journalism as a distant, removed, value-neutral observer, especially in politics, also persists. I don’t need to tell you how much damage the he-said-she-said model has done to campaign coverage. Even now, in the third election of the Trump era, we see media (not all media, all the time—but it happens far too often) laundering extremist disinformation into normal-sounding campaign stories. No wonder that a man who embodies the self-enrichment and rapacious profit-taking that Barlett and Steele skewered in America: What Went Wrong? is getting away with styling himself as a champion of the forgotten Americans.

But Don Barlett wouldn’t want us to stop there, at the doom and gloom. That’s why his obituary ends on that incredible honor of asking readers to support our work here at Mother Jones, Reveal, and the Center for Investigative Reporting. Our newsroom has not been taken over by hedge funders and it never will be. Our budget comes from you, the people who rely on our journalism to tell it like it is. And because we are accountable to you and you alone, we can do the kind of reporting that Don Barlett and Jim Steele did, and do it with the same commitment: exposing what is truly wrong, even if it’s completely legal.

Thank you, Don Barlett. We’ll do you proud.

For a personal tribute to Don Barlett, read “‘Hello, I’m Don Barlett and I Liked Your Story’” from our CEO emeritus, Robert Rosenthal.

It’s not often that an obituary truly surprises you, but the other day it happened to me in the best possible way. The person who passed wasn’t a relative, friend, or close colleague. But he did play a key role at one point in my life, by showing me what journalism can do—and often fails to.

Barlett was half of Barlett and Steele, a reporting duo as significant as Woodward and Bernstein, but in a very different way. When they worked for the Philadelphia Inquirer, they embodied the shoeleather investigative reporting that newspapers once nurtured. My colleague Robert Rosenthal, who was their mentee and friend at the Inquirer, has some moving (and funny!) recollections of the duo here.

But I wanted to zoom out a little, because the kind of reporting Barlett and Steele did is special, valuable, and endangered, and also because of the thing that surprised me in that obit: its last line. “Donations in his name may be made to the Center for Investigative Reporting, Box 584, San Francisco, Calif. 94104.” That’s us! The Center for Investigative Reporting is Mother Jones’ parent organization, and we are a bit of a Noah’s Ark for this kind of endangered journalism.

I was floored when I saw that line, and here’s why. In 1991, I was just out of journalism school, in the middle of a recession and the run-up to a presidential campaign, when Barlett and Steele published a series called America: What Went Wrong? It was a deep dive into the rising income inequality that had come to dominate the US economy.

The pair worked on the series (and subsequent book) for many months, and the book opens with a series of thank-yous that feel like a time capsule: “Lela Young, in the public reading room of the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington.” But what comes next could have been written yesterday: There are all these pundits on TV talking about how the economy isn’t so bad and everything will be fine, Barlett and Steele note. But then why does it not feel fine to so many people? Here we see a giant graphic that looks exactly like what you would make on your Apple Macintosh in 1991 (you can find it on page ix in the Google Books version). It shows that the top 4 percent of Americans make as much (just in wages, not counting investment income) as the bottom 51 percent.

Perhaps, Barlett and Steele wrote, it’s no wonder that “the stories you read in newspapers and magazines seem disconnected from your personal situation.” Those stories don’t talk about the factories and workplaces being shuttered, about millions of workers going from earning $15 an hour to $7 an hour. “For the first time in this century, members of a generation entering adulthood”—GenX—“will find it impossible to achieve a better lifestyle than their parents. Most will be unable even to match their parents’ middle-class status.”

These Americans, they write, look at the economy from the bottom up. “Those in charge, on the other hand, are on the top looking down. They see things differently. Call it the view from Washington and Wall Street.” Those folks include corporate execs, Republicans—led by Reagan and George H.W. Bush—who pushed through tax giveaways, trade deals, and deregulation, but also Democrats who went along with it.

Imagine the economy like a hockey game, Barlett and Steele continue, “a sport renowned for its physical violence.” Now imagine what the game would look like if you took away the rules and referees. “That, in essence, is what is happening to the American economy. Someone changed the rules. And there is no referee. Which means there is no one looking after the interests of the middle class. They are the forgotten Americans.”

It’s incredibly striking rereading, 33 years later, how accurately Barlett and Steele captured the dynamic that still defines our economy—and our politics. It’s also striking to remember how few mainstream journalists were doing that kind of reporting, and how many fewer do it now.

When I started in journalism, smack in the middle of that early-’90s recession, there were still a lot of investigative reporters in newsrooms, and they did great work, but there was something that defined most of those stories: They were about exposing people breaking the rules. Politicians stealing from the public purse. Construction workers catching naps on the taxpayer’s dime. Reporters exposed illegal acts, not ones that were merely unfair or inequitable. And there was a reason for that: Mainstream newsrooms had positioned themselves as carefully neutral; value judgments had no place in their work. But the mission of investigative reporting, inherently, is about showing the contrast between how things are and how they should be—it’s about exposing wrongs. Every investigative reporter since Ida B. Wells shone a spotlight on lynching has been animated by this.

Defining “wrong” as “rulebreaking” was a way to avoid making a value judgment—but it meant that a lot of important stories were not told. Stories about systems, especially, such as the growing inequality in the US economy.

That’s what made Barlett and Steele’s reporting so unique, and so powerful. What happened to incomes in America was wrong, it was right there in the book title. Not because it broke any laws (the point was that it was all perfectly legal!) but because it was unfair.

Seeing that journalism could do that—could expose not just lawbreaking, but systemic injustice—was an aha moment for cub reporter me. That’s the kind of work I wanted to be doing, and apparently there were jobs for people to do it.

Little did I know that most of those jobs were about to disappear. Investigative reporting is expensive, and the corporations and hedge fund investors who were buying up America’s newspapers had no intention of paying for it—or, ultimately, for any newsroom jobs. Since Barlett and Steele wrote their series, nearly half of America’s journalism jobs have disappeared (a loss rate faster than coal mining), and most of the rest are on borrowed time. There are very few journalists who can take the time to dig deep on a big issue, especially one as hard to get your arms around as income inequality.

And the idea of journalism as a distant, removed, value-neutral observer, especially in politics, also persists. I don’t need to tell you how much damage the he-said-she-said model has done to campaign coverage. Even now, in the third election of the Trump era, we see media (not all media, all the time—but it happens far too often) laundering extremist disinformation into normal-sounding campaign stories. No wonder that a man who embodies the self-enrichment and rapacious profit-taking that Barlett and Steele skewered in America: What Went Wrong? is getting away with styling himself as a champion of the forgotten Americans.

But Don Barlett wouldn’t want us to stop there, at the doom and gloom. That’s why his obituary ends on that incredible honor of asking readers to support our work here at Mother Jones, Reveal, and the Center for Investigative Reporting. Our newsroom has not been taken over by hedge funders and it never will be. Our budget comes from you, the people who rely on our journalism to tell it like it is. And because we are accountable to you and you alone, we can do the kind of reporting that Don Barlett and Jim Steele did, and do it with the same commitment: exposing what is truly wrong, even if it’s completely legal.

Thank you, Don Barlett. We’ll do you proud.

Human beings live every day with the understanding of our own mortality, but do animals have any concept of death? It's a question that has long intrigued scientists, fueled by reports of ants, for example, appearing to attend their own"funerals"; chimps gathering somberly around fallen comrades; or a mother whale who carried her dead baby with her for two weeks in an apparent show of grief.

Philosopher Susana Monsó is a leading expert on animal cognition, behavior and ethics at the National Distance Education University (UNED) in Madrid, Spain. She became interested in the topic of how animals experience death several years ago while applying for a grant and noted that there were a number of field reports on how different animal species reacted to death. It's an emerging research field called comparative thanatology, which focuses on how animals react to the dead or dying, the physiological mechanisms that underlie such reactions, and what we can learn from those behaviors about animal minds.

"I could see that there was a new discipline that was emerging that was very much in need of a philosophical approach to help it clarify its main concepts," she told Ars. "And personally, I was turning 30 at the time and became a little bit obsessed with death. So I wanted to think a lot about death and maybe come to fear it less through philosophical reflection on it."

© Princeton University Press

Last November, I asked Rashid Khalidi, the Edward Said professor of modern Arab studies at Columbia University and the most renowned Palestinian American historian today, about the lack of statements from President Joe Biden expressing sympathy for Palestinians. At the time, I was writing an article outlining Biden’s long-standing and unusual unwillingness to challenge Israel.

“I don’t really think he sees the Palestinians at all,” Khalidi replied. “He sees the Israelis as they are very carefully presented by their government and their massive information apparatus, which is being sucked at by every element of the mainstream media.”

The professional bluntness was typical of Khalidi. Throughout his decadeslong career as an academic and public intellectual, he has not shied away from lacerating fellow elites as he uproots deep assumptions about Israel and Palestine. In doing so, he has made himself a fitting successor to Said, the late Palestinian American literary critic his professorship was named after.

Khalidi’s 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, was called a “pathbreaking work of major importance” by Said. In the early days of the ongoing war, Khalidi’s most recent book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, became a New York Times bestseller. He is currently working on a study of how Ireland was a laboratory for British colonial practices that were later employed in Palestine. At the end of June, he retired and became a professor emeritus.

We spoke last Wednesday—one day after Iran launched ballistic missiles at Israel following a series of Israeli escalations—to assess the one-year mark of the current war.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

A year ago, more than 1,100 people were killed in Israel in Hamas’ October 7 attack. At least 41,000 people have been killed in Gaza in response. Now, Israel has invaded Lebanon and provoked a war with Iran, which launched ballistic missiles at Israel yesterday. A year ago, was this a nightmare scenario?

It is a nightmare scenario, but we may be at the beginning of the nightmare. This is potentially a multiyear war now. By the time this is published, we will have entered its second year. But the risks in terms of a regional confrontation are much, much greater than most people would have assessed back in October 2023. This is potentially going to be a world war, a major regional war, a multifront war. In fact, in some respects, it already is.

An article in the New York Times this morning stated that “Democrats cannot afford to be accused of restraining Israel after Tuesday’s missile attack.” The US has also said it will work with Israel to impose “severe consequences” on Iran. Are you surprised that there’s been essentially no willingness by the US to use its leverage over Israel?

I have to say I’m a little surprised. Firstly, because every earlier war, with the exception of 1948, was eventually stopped by the United States, or by the international community with the involvement of the United States, much more quickly than this one. You’ve had wars that went on for a couple of months. But eventually, after backing Israel fully, the United States stopped Israel. There’s absolutely no sign of the United States doing anything but encouraging Israel and arming and protecting them diplomatically. In historical perspective, this is unique to my knowledge.

Secondly, it is a little surprising in domestic electoral terms. I don’t think Biden and [Vice President Kamala] Harris have a whole lot to worry about on their right. People who are going to vote on this issue in one way are going to vote for [former President Donald] Trump anyway. Whereas on his left, I think one of the terrible ironies of this—we will only find this out after the election—might be that Harris loses the election because she loses Michigan. Because she lost young people and Arabs and Muslims.

To the left, there’s a huge void where some people are going to hold their noses and vote for Harris. But some people will not vote for her under any circumstances. And if that tips the margin in favor of Trump, it will be one of the most colossal failures of the Democratic Party leadership in modern history to not understand that there’s lots of space to their left and there’s no space to their right. They have hewed right, right, right on this—at least publicly. Personally, I don’t understand that electoral calculation.

I also go back to the first thing I said: I don’t understand how the United States doesn’t see that the expansion of this war is extremely harmful to any possible definition of American national interests.

What do you think the Biden administration and its supporters fail to understand in terms of the cost to the United States of enabling this war?

The administration and the entire American elite is in another place from Americans, who reject the Biden policy, want a ceasefire, and are opposed to continuing to arm Israel. That’s the problem. You have this cork in the bottle. The bottle has changed. The cork hasn’t.

The media elites, the university and foundation elites, the corporate elites, the donor class, the leaderships of the political parties, and the foreign policy establishment are way out in right field and are completely supportive of whatever Israel does. They back Israel to the hilt—whatever it does. And you are getting the same kind of mindless drivel in the foreign policy world about an opportunity for “remaking the Middle East” that we got before the 2003 Iraq fiasco.

Israel killed the guy they were negotiating with in Tehran—[Ismail] Haniyeh. They don’t say anything. You want a ceasefire? Haniyeh allegedly wanted a ceasefire. Israel goes and kills the guy in Tehran. The US doesn’t say anything. Not a peep. This is a high-level provocation.

[Harris] and the Democratic Party establishment have obviously made a decision that they can spit at young people who feel strongly about this.

You’re trying to bring about a ceasefire on the Lebanese border? The Israelis kill the person they’re negotiating with. Not a peep. The US says: He was a bad guy. He killed Americans. Good thing.

I find it mind-boggling the degree to which the elite is blind to the damage that this is clearly doing to the United States in the world and in the Middle East—and the dangers that entails. I hear not a peep out of that elite about the potential danger of Israel leading them by the nose into an American, Israeli, Iranian, Yemeni, Palestinian, Lebanese war, which has no visible end. I mean, where does this stop?

Harris has declined to break with Biden on Israel in her public rhetoric. If she’s elected, do you expect a significant shift in her approach to Israel and Palestine?

No, I do not. She had multiple opportunities to do a Hubert Humphrey—to disassociate herself from the president who just decided not to run again. To allow a Palestinian speaker at the [Democratic National] Convention, to meet with certain people, to modulate her virulent, pro-Israel rhetoric, she hasn’t taken those opportunities. I don’t expect that she will.

She and the Democratic Party establishment have obviously made a decision that they can spit at young people who feel strongly about this. They can ignore Arabs and Muslims, and then they can win the election anyway. That seems to have been their decision. That might change if their internal polling at the end of October shows she’s losing Michigan. But it would be a little bit late.

Humphrey’s speech was on September 30. So we’re already past that.

And it was too late for Humphrey.

The main success that Biden administration officials pointed to again and again was preventing a regional war. That has now completely fallen apart. You were in Lebanon during the 1982 Israeli invasion with your kids and your wife, Mona, who was pregnant at the time. How does your personal experience of that invasion influence how you see what is happening in Lebanon today?

It’s not deja vu for me. I actually feel it’s much, much, much worse. I’m following along with all my relatives in Beirut, as I have been following along with relatives in Palestine over the past year, as they report on what’s happening to them and around them. It’s similar, but it’s a lot worse. I think my kids are going through the same thing, especially my daughters, who were little children during the ’82 war.

And all of us are sitting in safety outside the Middle East. I’m thinking of the family that we have who are still in Beirut. They’ve been through war and misery and the collapse of Lebanon and various phases of this war in the past. I know they are resilient. But it’s really hard to experience it again and again and again. They went through it in 2006 and now they’re going through it again.

It’s horrifying that nobody seems to read history or understand that no good can come from this. Leave aside good for the Lebanese—obviously, nobody in the Western elite cares about the Lebanese or the Palestinians. There’s a degree of insensitivity, which is shocking, but we’re used to it. But nobody even cares about the Israelis. They are putting their head into a buzz saw in both Gaza and Lebanon: a tunnel without end.

What do the Americans think they are doing, pushing, allowing, arming Israel to do this vis-à-vis Iran, vis-à-vis Yemen, vis-à-vis Lebanon, vis-à-vis the Palestinians? Where does this end for Israel? They are getting themselves into a minefield out of which they will not be able to extract themselves without enormous, terrible results for them—and obviously infinitely more devastating results for Lebanon and the Palestinians.

I don’t understand the blindness of the United States in basically encouraging Israel to commit harakiri. This cannot end well for them. It’s not going to end well for anyone else. I’m not minimizing the horror. It’s going to end worse, obviously, for Palestinians and Lebanese. But what can they possibly be thinking in Washington? Or, for that matter, in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem?

Perhaps the most horrifying result of the 1982 invasion was Sabra and Shatila, when Israeli soldiers assisted Lebanese Christian militants as they slaughtered thousands of Palestinian and Lebanese Muslims inside the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. You and your family were staying in a faculty apartment that Malcolm Kerr had found for you after American and international troops pulled out of Beirut. Could you talk about what you saw from the balcony of that apartment?

What we witnessed was the Israeli military firing illumination shells over Sabra and Shatila after they had introduced militias that they paid and armed to kill people on the basis of an agreement between [Israeli Defense Minster Ariel] Sharon and the Lebanese forces. We were a little shocked because the fighting had stopped a couple of days before. The Israelis had occupied West Beirut. There were no Palestinian military forces at all in Beirut. No fighters, no units, nothing. The camps were defenseless, and the Americans had promised the PLO that they would protect the civilian populations left behind when the PLO evacuated its forces.

So, we were quite perplexed. What is going with these illumination shells being fired when it seemed completely quiet? We went to bed not knowing the massacre had started. When we woke up, we found out from Jon Randall and Loren Jenkins, who were working for the Washington Post, what they had just seen.

When we spoke in November, you held up your phone so that I could hear pro-Palestine demonstrations passing by you in Morningside Heights. Edward Said had the opposite experience decades before.

He said he was radicalized by being in New York during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War and talked about hearing someone in Morningside Heights ask, How are we doing? It drove home that Arabs and Palestinians effectively did not exist. What do you make of the significance of that shift?

I was in New York in June 1967, and I remember people collecting money for Israel in bedsheets outside Grand Central station. The same fervor that Edward witnessed, I witnessed in ’67. There’s been an enormous shift in American public opinion. The polling numbers are unequivocally opposed to this war, opposed to Biden’s policy, opposed to continuing to arm Israel.

We’ve seen it on campus. The campus has been shut down in response to last year’s protests. We call it Fortress Columbia. You can’t get a journalist onto the campus without two days’ notice, and even then, it doesn’t work. Columbia has sealed the campus and installed checkpoints to prevent the people of the neighborhood from walking across the campus on what should be a public thoroughfare on 116th Street.

The protest movement has been shut down by repression, but the sentiment is I’m sure still there. Most young people have an entirely different view of this war—and of Palestine and Israel—than their grandparents have. The difference is enormous and striking, and I think it may be growing. The invasion of Lebanon will do nothing to change the way people see things. I think it will just reinforce it.

I’ve seen a sea change in the past couple of decades that I was at Columbia. I arrived there in 2003, and sentiment was not favorable to Palestine overall. I still had the sense that I had when I was an undergraduate many decades ago that I was swimming against the tide of opinion among students and faculty. That’s not the case anymore. Two-thirds of the arts and sciences faculty voted no confidence in the president because of her position on the protests. I couldn’t have imagined something like that happening 25 years ago.

Do you ever fear that the shift is arriving too late? That by the time America potentially decides to hold Israel accountable, there might not be a Palestine left to save because the West Bank has been annexed and Gaza has been leveled?

Gaza has been leveled, and the West Bank has long since been annexed. It’s been incorporated into Israel in practice for decades. Israeli law operates in the West Bank for Israelis only. Palestinians are being squeezed into smaller and smaller Bantustans, and Israel is encouraging them to leave. But that doesn’t mean that Palestine is gone. You still have as many Palestinians as Israelis within the frontiers of Palestine. That’s not going to change.

They still have a problem. How do you establish an entity involving Jewish supremacy in a country where at least half of the population are not Jews? I don’t see how they get out of that conundrum just because they’ve devastated Gaza or just because they’ve annexed the West Bank.

They’ve created that conundrum and there’s no way out for them. They either entirely annihilate the Palestinian population or drive it out, which I don’t think is possible in the 21st century, at least I hope not, or they come to terms with it. They’re not willing to do that right now. They’re even less willing to do that after October 7. Public opinion has hardened in Israel for reasons that are perfectly understandable.

But do I see that this is too late? No. I worry that no matter how consequential the shift in public opinion is, the elite will hold on stubbornly. And that it will take even longer than it took for public opinion opposing the Iraq war or public opinion opposing the Vietnam War to force elites that were dedicated and committed to mindless, aggressive wars abroad to finally change their course. It took years and years on Vietnam, and it took years and years on Iraq.

That’s what I’m afraid of—that the anti-democratic intent of the elite, and of the party leaderships, of the foreign policy establishment, and of the donor class will prevent a shift for many more years than should be the case. If we had a really democratic system, if we had a system where public opinion had as much of an effect as money—which it doesn’t, unfortunately—then you would have seen a change already. There’s no indication that there will be a change for quite a while, regardless of who is elected in November.

A consequence of timing this interview to coincide with the one-year mark of the war is that it can obscure what came before. How should the reality of daily life in Gaza in the decades leading up to October 7 shape how we understand what has happened in the past year?

The people who have been fighting Israel in Gaza, for the most part, are people who grew up as children under this prison camp regime imposed on them by the Israelis and on the southern border by the Egyptians. Most of them have never been allowed to leave Gaza. Most of them have had all kinds of restrictions on everything they can do and buy and say for their entire lives. And they’ve lived under an authoritarian Hamas regime, which was quite unpopular in Gaza before October 7.

The people who have been fighting the Israelis are the people who Israel’s prison camp has created. And what Israel has done in the last year is far, far worse than anything it did in the preceding 17 years of the blockade. They killed over 2,300 people in 2014. They’ve killed probably well over 50,000 in the past year, if we count those buried under the rubble. The number is 41,600 as of today. The numbers are hard to process.

The kids growing up now are going to be the successors to today’s fighters, given that nobody’s offering them a future, given that they’re going to live in misery for a decade if not longer, given that Israel will dominate their lives in even more intense ways than it had before. The people who grow up in that situation—some of them are going to turn into even more ferocious fighters resisting Israel.

The same thing is happening in South Lebanon. People grew up in South Lebanon being bombarded by Israel, and they became the fighters in the ’82 war. There’s a picture of [former Hezbollah leader Hassan] Nasrallah fighting in ’82 as a young man. That experience of constant Israeli attacks and the occupations of South Lebanon in ’78 and ’82 created Hezbollah. Even Ehud Barak admitted as much.

I’ve seen not one mention of the fact that the United States helped Israel kill 19,000 people in Lebanon in 1982. And that might have been a factor as important as what Israel was doing in creating Hezbollah and in it turning against the United States. They considered the United States responsible for Sabra and Shatila because it had promised to protect the civilians—that no harm would come to the civilians the PLO left behind.

I fear that the United States’ full-throated support for what Israel is doing may have the same effect in the 2020s and 2030s, unfortunately. I’m not happy about any of this. I consider all of these things disastrous. But I’m looking at them coldly. The things that I’m talking about have produced what has passed, and what we’re seeing now will produce, heaven forbid, possibly even more horrible things in the future. Those who don’t read history and don’t understand history are condemned to repeat it, but in a much worse way, I’m afraid.

“Today’s newsletter will probably overwhelm you,” Jessica Valenti wrote in a note preceding the Wednesday, September 25, edition of Abortion, Every Day, the Substack where she breaks down the news on reproductive rights. The first order of business: an explanation of how a powerful anti-abortion group is directing an ad campaign that blames pro-choice advocates for the deaths of Candi Miller and Amber Nicole Thurman. Miller and Thurman were two Georgia women who, according to a ProPublica investigation, died because of the state abortion ban. “Honestly, how dare they,” Valenti wrote. “How dare they use these women’s names; how dare they use their pictures. It’s just beyond the pale.”

The same newsletter also covered Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ efforts to oppose adding the right to abortion to the state constitution, a report on the increasing criminalization of pregnancy since the end of Roe v. Wade, and a summary of a New York Times/Reveal investigation into Florida maternity homes. That wasn’t even all of it—and that was just Wednesday.

Valenti, known for her previous columns at the Nation and the Guardian, has written about feminism and politics for nearly two decades. She started Abortion, Every Day almost immediately after the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling leaked, when she found herself unable to turn away from the news. “It was not a deliberate pivot,” she tells me in a phone interview as she prepares dinner for her family in Brooklyn. “I was just so mad and upset. Like so many people, I think I just wanted to know everything, so I just started writing about it.”

She never stopped. “Hilariously,” Valenti says, “I really did ask myself in the beginning, ‘If I do this, am I going to have enough stuff to write about every day for more than a few months?’” Now, Valenti writes a newsletter every day of the workweek—mostly on her own, though she recently hired an assistant and a part-time researcher. She’s also gathered enough material to fill a new book, Abortion: Our Bodies, Their Lies, and the Truths We Use to Win, out this month. From the very beginning of Abortion, Valenti makes the case that the deluge of news is itself a part of the anti-abortion movement’s strategy. “The anti-abortion movement is hitting Americans with everything all at once in the hopes that those of us who want our rights back will be too exhausted and crushed to fight back,” she writes in the introduction. “It’s hard for any single person to keep track of all the anti-abortion attacks and tactics happening in different states around the country. But it’s vital that we do.”

It’s only by tracking the day-to-day onslaught that Valenti says she and, by extension, her readers can see the full scope of the attack on abortion rights. “I can see a difference in my own knowledge if I skip a day in the newsletter,” she says. “Things are moving so quickly.” If that seems exhausting, well, it is. “I think everyone who is working on this issue is in a very similar place, and I worry about burnout for myself and everyone who does this work because you can feel the impact physically,” Valenti says. “You start losing sleep. It takes a toll on your health.” Since beginning the newsletter, Valenti says she’s given up on seeing almost anyone besides her husband and 14-year-old daughter, Layla.

Layla is the reason Valenti does this work. “It was her I cried for the night the Dobbs decision was leaked,” Valenti writes in Abortion. “I remember crawling into bed with my husband and sobbing. Wailing, really. I kept saying, ‘My daughter, my daughter.’ A mother’s job is to protect her children. How could I possibly do that now?” The newsletter, and now the book, were the answer. The twist is that the work dedicated to Layla pulls Valenti away from her. “She went from having a mom who is writing a weekly column and who is super-present to someone who’s just not,” Valenti says. “It’s a mind fuck, that’s for sure.”

Although Abortion, Every Day began almost by accident, Valenti has in some sense been preparing her whole career for this. After earning a master’s at Rutgers University in women’s and gender studies, she worked as a communications assistant for a feminist organization. A friend encouraged her to start blogging, and in 2004, she and sister Vanessa founded Feministing, which would become one of the most widely read feminist publications in the country during its 15-year existence, with more than 1.2 million unique monthly readers at its peak.

The goal behind her writing was to give young feminists the tools they needed to speak more confidently about their beliefs. “One of the things that I heard, and continue to hear most often, especially from younger women, is this feeling like someone is going to think that they’re stupid or that they don’t know what they’re talking about,” Valenti says. “So the hope was to provide the language, the context, the information that folks needed to say the stuff that they already believed but didn’t necessarily have the language for.”

That idea continues to be a driving force behind Valenti’s work on Abortion, Every Day and her new book. At the back of Abortion, there is a section of quick facts (“Decades of research have shown that both procedural and medication abortions are safe”) and statistics (“States with abortion restrictions have maternal death rates that are 62 percent higher than states with abortion access”) designed so readers can quickly find what they want to reference when talking about the issue, whether that’s on social media or face to face with family and friends. “Sometimes people ask me if I feel like I’m ‘preaching to the choir.’ What I tell them, and what is true about this book, is that I’m arming the choir,” Valenti writes in Abortion.

Valenti wasn’t always the type of person who could pull these kinds of facts from memory herself. “I was not a wonk by any means,” she says. “I could not tell you about ballot measure shit two years ago. It was not something that was on my mind at all.” But her blogging days gave her a bit of a head start on keeping up with the strategy. In 2009, she published The Purity Myth, an investigation into America’s obsession with virginity. Now, she says, the people she wrote about then, who were focused on anti-sex education campaigns, have come back to haunt her. “It really is all the same people,” she says. “They’re still doing the same thing, and honestly, it is a little weird because they’re using the same tactics, they’re using the same language. They haven’t changed much, which shouldn’t surprise me, but it does.” The difference now is that she knows that the fight is not just about purity, or even just about abortion. It’s about birth control, freedom of movement, and defending democracy. It’s more existential.

Although the subject she covers is obviously heavy, there’s a certain catharsis for Valenti in connecting all the dots in her newsletter and book, in unmasking a movement that’s been encroaching on abortion rights for decades. Valenti says that before Roe was overturned, abortion advocates often felt “gaslit, not just by anti-abortion people, but by leftist dudes and pundits who were like, ‘You’re being hysterical,’ and, ‘Don’t scaremonger.’”

The fight is not just about purity, or even just about abortion. It’s about birth control, freedom of movement, and defending democracy. It’s more existential.

Now, all the threats she and others warned about have become reality. It’s, as Valenti puts it, “horrible and also so incredibly fucked,” but after the years of being called hysterical, it feels good to read someone who is honest about the situation and still as angry as she was two years ago. “It’s a terrible thing to write about every day, to read about every day, to think about. Unfortunately, it’s also something we can’t escape, because it is happening,” she says. “My fear is people reading these stories and sort of being like, ‘Oh man, that’s horrible,’ and turning the page. There’s a reason they’re trying to overwhelm us, right? They know that they can make us numb to it.”

Part of what keeps Valenti from becoming numb is the occasional joy she takes in the ability to “fuck some of them over.” Take, for example, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall, who said in a 2022 interview that his state’s abortion ban does not criminalize mothers. While searching through news for Abortion, Every Day, Valenti found a comment from Marshall’s office to a local conservative blog, assuring concerned readers that even though the abortion ban wouldn’t allow women to be prosecuted, it wouldn’t stop the office from charging women who had medication abortions under a chemical endangerment law meant to protect children exposed to drugs. “In other words, Alabama’s Attorney General plans to arrest and charge women who take abortion medication…using a law meant to stop adults from bringing kids to drug dealers’ houses,” Valenti wrote in her newsletter. “So much for not jailing women!”

Marshall’s office’s comment to the blog hadn’t otherwise been reported, but after Valenti wrote about it in Abortion, Every Day, it was picked up in local and national outlets. Two days after her newsletter, Marshall backtracked, telling the press that women would not be prosecuted for taking abortion pills.

“What makes me happy about the project are the people who are reading it,” Valenti says. Her readers include people who work directly in abortion access, but also Senate staff and reporters. A few times a month, Valenti says she’ll read a piece she feels like she could’ve written herself and, when she types the reporter’s name into her subscriber list, is delighted to find them there. “It’s been really amazing to see the growth of reporters,” she says. “As horrible as it is, since we’re gonna have to be doing this for a long time, I hope that we’ll see a new generation of reporters who started writing about this issue when they were young and then are just gonna be so outrageously knowledgeable 10 years from now.”

Ten years from now is hard to imagine. Ten years ago, we still had Roe, but the anti-abortion movement was taking hold in the states. The Guttmacher Institute issued a worrying report in 2014 on “an unprecedented wave of state-level abortion restrictions.” A February article in Time that year described how anti-abortion advocates were “looking to turn abortion into an animating issue for the Republican Party.” Valenti was just beginning her stint at the Guardian. She sometimes wrote about abortion in her column. When someone emailed her, she’d get back when she could. It wasn’t urgent.

Now, the emails in Valenti’s inbox come from 17-year-olds who are wondering where they can get abortion medication, from people seeking legal advice, from people whose stories need to be told now. Maybe, Valenti says, she could see herself slowing down the pace of her work in a world with reasonable federal abortion protections. But for now, 13 states have a total abortion ban. Hospitals in those states are unable to recruit OB-GYNs, and maternal health wards are closing. Anti-abortion groups are sowing distrust about birth control. Some pregnant women are being prosecuted; others are bleeding out in parking lots. “No matter what happens in November, we’re still going to be fighting this fight for years, if not decades,” Valenti says. So she will continue tracking the daily churn of legislation moving through statehouses, politicians making crude remarks, and reports on the impact Dobbs has had across the nation. She has to.

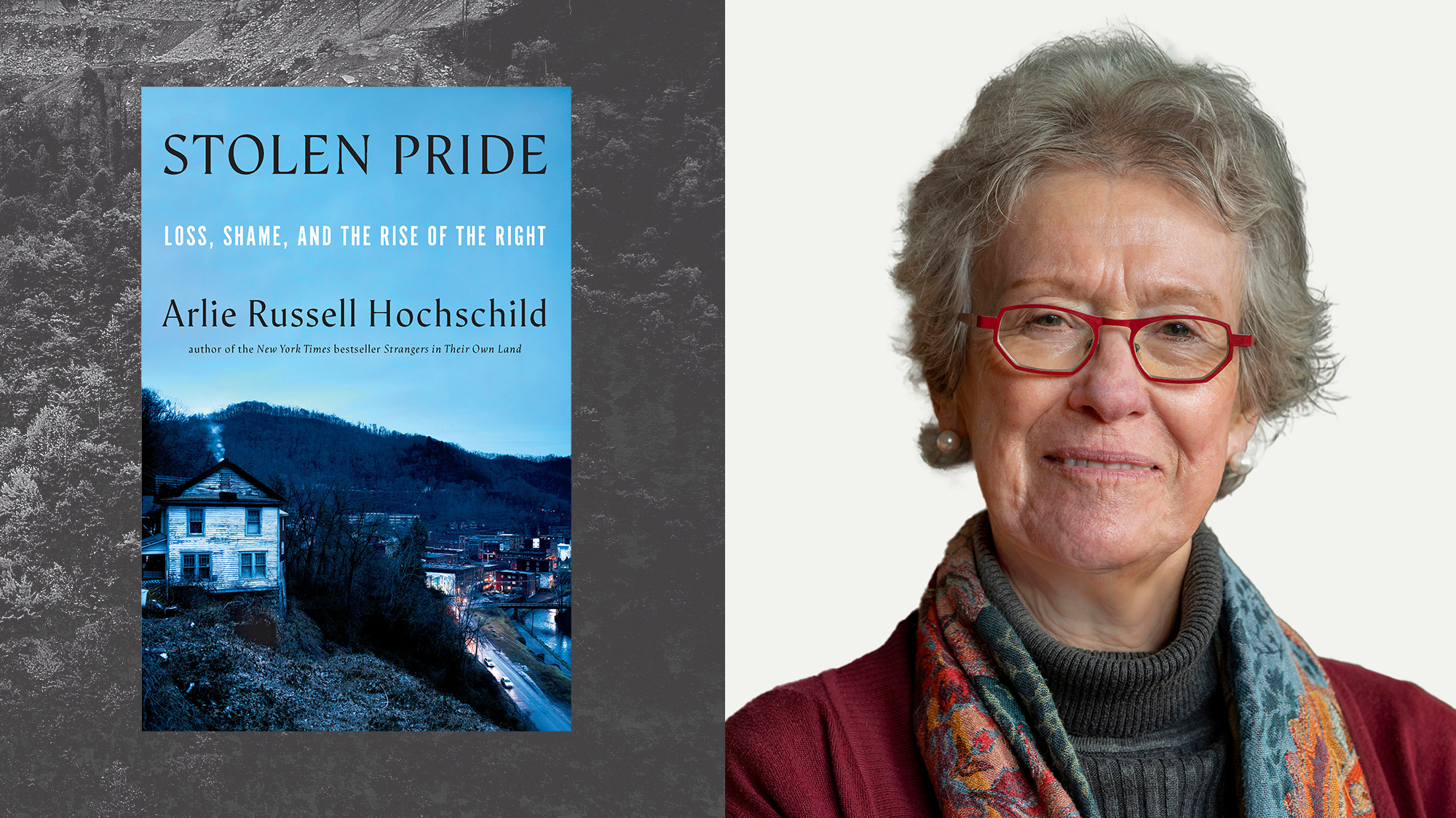

Editor’s note: Eight years ago, on the eve of the 2016 election, Mother Jones published a story by Arlie Russell Hochschild, a renowned sociologist who had spent five years interviewing a group of white Southern conservatives to understand what drives the way they see America, politics, and Donald Trump.

Trump was not the focus of Hochschild’s research, but she soon discovered that he was there in the background, tapping into the “deep story” her interviewees told about themselves and their community. They saw themselves, she wrote, as waiting patiently in line for their shot at the American Dream—but others, whom they saw as undeserving and who were often Black or immigrants, were cutting in line. “The government has become an instrument for redistributing your money to the undeserving,” they believed. “It’s not your government anymore; it’s theirs.”

It didn’t matter if that story was factually true (Hochschild documented that it was not): It drove how people felt and how they would ultimately vote. It gave them an explanation for why the success they had been told was their birthright seemed elusive, why their families might even need benefits like food stamps or disability income that they had been told only the weak would accept.

“Trump solves a white male problem of pride,” Hochschild wrote. “Benefits? If you need them, okay. He masculinizes it. You can be ‘high energy’ macho—and yet may need to apply for a government benefit. As one auto mechanic told me, ‘Why not? Trump’s for that. If you use food stamps because you’re working a low-wage job, you don’t want someone looking down their nose at you.’”

Trump would not, of course, deliver on these voters’ economic needs. But he would deliver on their need for pride. And it’s that issue that Hochschild returns to in her new book, Stolen Pride, set in the heart of what Trump calls the forgotten America—the town of Pikeville, Kentucky.

In 2017, when Hochschild’s research for this book began, Pikeville was the site of a neo-Nazi march that became a prelude for the deadly rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The march was a focal point for Hochschild’s interviews with everyone from an imprisoned white supremacist gang member to a self-described “trailer trash” TikTok creator. In Pikeville, the deep story was all about what Hochschild came to call the pride economy.

“We live in both a material economy and a pride economy, and while we pay close attention to shifts in the material economy, we often neglect or underestimate the importance of the pride economy. Just as the fortunes of Appalachian Kentucky have risen and fallen with the fate of coal, so has its standing in the pride economy…

“And our place in the material economy is often linked to that in the pride economy. If we become poor, we have two problems. First, we are poor (a material matter), and second, we are made to feel ashamed of being poor (a matter of pride). If we lose our job, we are jobless (a material loss) and then ashamed of being jobless (an emotional loss). Many also feel shame at receiving government help to compensate that loss. If we live in a once-proud region that has fallen on hard times, we first suffer loss, then shame at the loss—and, as we shall see, often anger at the real or imagined shamers.”

In places like rural Kentucky, that sense of shame and lost pride is connected to what Hochschild identifies as the paradox of the American Dream: A self-sufficient, middle-class life has become harder to attain in many rural, conservative communities—but people in those communities are more likely to blame themselves for this.

“From roughly 1970 on, the United States gradually divided into two economies—the winners and losers of globalization. Rising in opportunity have been cities and regions with diversified economies, often the site of newer, less vulnerable industries, which typically hired college-educated workers in service and tech fields. Declining in opportunity have been rural and semi-rural areas, offering blue-collar jobs in older manufacturing industries more vulnerable to offshoring and automation. These also include regions where jobs are based on extracting oil, coal, and other minerals, the demand for which fluctuates with world demand.

“The urban middle class, which leans Democratic, has become a so-called mobility incubator, while many rural blue-collar areas, now leaning Republican, have become mobility traps. Between 2008 and 2017, one study found, the nation’s Democratic congressional districts saw median household income rise from $54,000 to $61,000, while incomes in Republican districts fell from $55,000 to $53,000…The second part of the paradox lies in core ideas about hard work and individual responsibility for one’s economic fate.

“When asked in a national survey why it is that a person ends up being poor, 31 percent of Republicans (party members or those who lean that way) say it is due to ‘circumstances beyond their control,’ in contrast to 69 percent of Democrats. Similarly, 71 percent of Republicans but only 22 percent of Democrats think ‘people are rich because they work hard.’…Thus, people growing up in the two kinds of economy experience different degrees of moral pinch between the cultural terms set for earning pride and the economic opportunity to do so.”

It’s this moral pinch—being caught in a declining regional economy while being told you have yourself to blame for your economic struggles—that the people Hochschild interviews describe from a variety of angles. For some, it fuels hate; for many, resentment; for all, a kind of bewilderment.

Like Hochschild’s 2016 book, these stories are even more timely now than they were when she conducted the interviews, in part because of Trump’s running mate selection of JD Vance, whose fame began with his book, Hillbilly Elegy. But where Vance concludes that the fix for places like Appalachia is to exclude others from the economy—both the material and the pride kind—Hochschild’s interviewees offer more nuanced views. All but one reject the white supremacists marching through their town. But many also are drawn to the way Trump and Vance make them feel seen. She talks with TikTok creator David Maynard, born literally yards away from Vance’s ancestral hometown of Jackson, Kentucky, and his wife, Shea, who show her the places where they grew up, fell in love, and built a life together. It’s a “reverse Hillbilly Elegy,” Hochschild writes, a story of wrestling with the paradox of the American Dream.

“If I’m a Moore’s Trailer Park white trash person, the only narrative I have tells me that I’m white, so I’m privileged,” Maynard tells Hochschild. “That’s the something I have and that must put me ahead. But what if it doesn’t put me ahead? I’m left with nothing because I’m lazy and stupid. There’s no excuse. If you’re white and poor, people think, ‘What’s wrong with you that you’re stuck at the bottom?’”

Another of Hochschild’s interviewees, Tommy Ratliff, digs deeper into that sentiment: “I could have become a white nationalist,” he tells her. Why that’s so, and how he didn’t, is the subject of the chapter excerpted below. —Monika Bauerlein

“In college,” Tommy Ratliff told me, “we had a guest speaker who gave us a lecture on the American Dream. He told us all we had to do was to work real hard, stick to a plan, and open a bank account. We should save a little money each month for our kids’ future education. At the time, I was earning $9.50 an hour behind the counter at a hobby shop and had to repay a loan I took out to pay for college and child support. Part of me just felt like telling the guy, ‘Shut up.’”

A tall man with long, wavy brown hair fanned across broad shoulders, gentle and direct in manner, Tommy was wearing his favorite black T-shirt, which said, “Not perfect, just forgiven.”

“Maybe I could earn my way to the American Dream if nothing else went wrong. That’s if I don’t get sick, if I don’t need a new heat pump, if my electric bill weren’t $400 a month, if my ex-wife didn’t get hooked on drugs, if my parents weren’t alcoholics, if my disturbed brother didn’t move in with me and raid my refrigerator while I was at work. Sure, the American Dream is all yours if nothing goes wrong. But things go wrong.”

Tommy explained what that meant as we walked through maple, redbud, and pines around his natal family’s quietly sheltered valley enclave. We walked by the home of his Uncle Roy, now widowed and seldom home. Roy had gotten Tommy out of scrapes, bought him a car, lent him money. Roy’s wife, Tommy’s aunt, became the “one I was closest to” when words became slurred and voices were raised in his own home next door.

We passed a shed used by Tommy’s paternal grandfather, now deceased, a former miner and World War II vet who had been at Iwo Jima as American GIs raised the flag. He had been decorated with a Purple Heart, long proudly kept like a holy icon in a glass cabinet in his grandfather’s hallway. A nearby shed held his grandfather’s beekeeping equipment and a wooden cane he had made in his retirement, together with a long wooden chain miraculously carved from a single piece of wood.

Visiting the small hillside cemetery near the end of a logging road where Tommy’s ancestors were laid to rest, we ran into Tommy’s Aunt Loretta washing family gravestones and restaking the VFW flag by his grandfather’s grave. A retired nurse, Loretta enjoyed Civil War reenactments but was uninterested in Pikeville’s upcoming white nationalist march. “Those guys come and go. I don’t pay them mind,” she said.

“The very idea that I had a place on a class ladder came to me slowly,” Tommy mused. “First, I thought of my family as middle class, and I was proud of that. As a kid, class was a matter of the kinds of toys I got at Christmas. Don’t get me wrong. I was happy to get what I got—GoBots, Action Max, Conan the Barbarian, Turok, the Warlord. But the kids at school had better-made versions of the toys I got. So, in toys, I felt somewhere below the middle.” Then when Tommy’s mother’s Texan relatives came to visit, he said, “I could see they looked around and thought my mom had married down and felt sorry for us. One cousin asked me, ‘What do you think a redneck is?’ and I wondered why she asked me that. Did she think I was one?”

We walked along a dirt path to a gurgling stream in back of Uncle Roy’s and Aunt Loretta’s homes—a wondrous wooded childhood haunt, filled with pine, poplars, birch, and pawpaw trees, that Tommy had long ago christened “Fairyland,” a term he still used with reverence.

“After 14 or 15, I used to spend a lot of time in this forest,” Tommy recalled, looking around at the trees as if at the faces of dear friends. “George [a childhood pal] and I would fight monsters and trolls and orcs and talking animals, like we saw in films about Narnia. We wore rounded strips of tree bark as body armor and used sticks as swords. I’d catch salamanders, frogs, and crawdads from the stream and let them go. We didn’t fish or hunt; we thought everything should be left the way it is. If you listened really close to the crickets and frogs sing to each other at night, first a song would come from one bank of the stream, then we’d hear an answer from the other. In the winter, we’d walk up the frozen streambed on the ice, then slide all the way down.” Listening to Tommy, I was reminded of a passage in Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow: “Aunt Beulah could hear the dust motes collide in a sunbeam.”

“Growing up, my world was real small—Elkhorn, Dorton, Belcher, Millard, Lick Creek, places around our holler. I didn’t know what was going on outside my family and neighbors and these places,” Tommy said. “Elkhorn only had one red light, but it was a city compared to Dorton, nothing there except the school and a pizza place. Dorton was tough. In a lot of hollers, people only come out once a month [to shop or visit] and don’t like outsiders. Nearly everyone in my world—my parents, my two brothers, my best friend George, my neighbors and schoolmates, and the action figures we played with—were all white.”

When, after finishing high school and working a few jobs, Tommy enrolled at Clinch Valley College in Wise, Virginia, he made his world smaller still. “Dad never liked me or my brothers to talk. If we were at dinner, he told us, ‘Don’t talk.’ If we were in the car, it was ‘Don’t talk.’ If we had company, ‘Don’t talk.’” So at Clinch Valley, Tommy sat in the back of a large classroom, was assigned to no discussion group or advisor, feared going to his professor’s office hours, and never talked. At the end of the first semester, Tommy flunked out, imagining that he, not the college, had failed.

“I’m not sure if I wasn’t paying attention or if it wasn’t taught. But before college, honestly, I wasn’t very sure how Blacks got to America,” Tommy told me. “I learned about slavery from seeing Amistad [a film about a slave ship rebellion in 1839] and 12 Years a Slave [about a free Black man kidnapped and sold into slavery], and about the Holocaust from Schindler’s List.”

Tommy also learned about Black life through television: “For a while, we didn’t own a TV. Dad would rent one in his name and when the bill got too high, Mom would put it in her name. I watched The Cosby Show and thought those kids were a whole lot better off than I was. They got an allowance, and all they had to do was save it. Their parents didn’t yell or drink. They lived in a nice house, and the dad was fine with them talking.”

Yet in one program about Black family life, Tommy suddenly recognized his own. “I watched and loved every episode of Good Times,” a 1970s sitcom about a Black family in Chicago that struggled with such things as job losses, a car breakdown, and an eviction notice. “In one scene,” Tommy recalled, “the wife, Florida, is talking to her girlfriend, who confides, ‘I can always tell when it’s Saturday morning because I wake up with a black eye.’”

“What got me wasn’t the story. It was that people laughed at it. Florida’s friend laughed. Florida laughed. On the TV soundtrack, the audience laughed. As a kid, I remember wondering: Why did they all laugh? At night, I’d crawl into bed with my older brother. I could hear my dad downstairs drunk, yelling and cursing at Mom, hitting her, shoving her against the wall, and shouting, ‘That didn’t hurt!’ Mom was yelling at Dad, ‘Stop it!’ I was scared. I wanted to cry.”

As Tommy grew up, his parents’ lives spiraled. “In the 1980s, when I was in high school, Dad lost his job guarding a mine and got a job as a supervisor in a lumberyard. When the lumberyard closed, Dad worked for my Uncle Roy’s road crew cutting grass along public roads with a dozer at minimum wage. That’s when we fell behind in taxes. When my father fell off the dozer and injured his back, his doctor discovered he had cancer.” As funds ran down, Tommy said, “we went from three cars to one, which we could barely keep running. We applied for food stamps, which bothered my dad terribly. I wondered: Had we become that class of family? We felt ashamed.”

Then Tommy’s parents began to drink themselves farther downward. “Dad drank Early Times whiskey with Tab and Mom drank vodka with Sprite—all day long. By 6:00 p.m., I’d try to leave. They argued. Mom would cry. Dad would get mad at her crying. That’s when I heard him shout, ‘That doesn’t hurt.’”

The family house fell into disrepair and his parents moved out of it into a trailer, then asked to move in with one troubled son after another until, one by one, they died.

In the wake of his parents’ decline, Tommy’s own ordeal unfolded. An acquaintance asked him if she could move into his trailer to save on rent. The two became involved, she became pregnant, and at 19, Tommy married and briefly imagined he was glimpsing a life of satisfaction and pride. “I got baptized at the Free Will Baptist Church in a creek one midnight in December, total immersion. One man held my back, another my head. It was cold and I got sick. When I got better, I got a union job at Kellogg’s biscuit factory. We moved near her folks in Jenkins, and I thought, ‘For my American Dream, this is good enough,’ and it would have been if she’d been the right woman.”

But she was not. The baby was too much for her. The house was left in disarray. Tommy’s addicted brother moved into a spare room. Returning late from his job at Kellogg’s, Tommy had a head-on collision. When, after his medical leave, he tried to return to his job, Kellogg’s fired him.

Jobless, with a wife and child to support, with $225 due monthly for rent and $100 for power, Tommy began scavenging aluminum cans out of ditches to recycle, $25 per bunch. Other luckless neighbors competed for the good cans. “I knew people looked down on me because I knew how I looked at other people scrounging cans. But part of me still thought, ‘I’m not that kind of person.’ I’d spend a few hours visiting with Uncle Roy before I got around to asking to borrow money. He’d know why I came, which was embarrassing. I’d borrow his car if mine broke down or I was driving mine with dead tags. I looked for work, but you had to pass the drug tests first, and for a while, I was trying muscle relaxants, Valium, Ativan. Then it got to half a case of beer, then more.” After Tommy’s marriage dissolved, his loving and nondrinking in-laws took in Tommy’s son. Now, with Tommy on his own, his heavy drinking grew worse, from occasionally to every day, from with someone else to alone, to alone and a lot.

Drinking had its own pride system, Tommy discovered. “At the top were guys who could hold a lot without getting sloppy drunk, pay for the drinks, and share the high. In the middle ranks were angry drunks. There was a rule to never talk politics, so angry drunks would be mad at ‘the man keepin’ us down.’ At the very bottom of the hierarchy were the crying drunks. I was a crying drunk.”

Our walk through Fairyland was taking us to a cluster of branches, a long-ago-collapsed teepee Tommy and his pal George had once built as boys in a moment of childhood triumph, and Tommy began to relate the hardest moment of his life. “We all have different bottoms,” he reflected softly. “I reached my bottom when I overheard my dad—whom I’d always assumed was my real dad—call me his stepson. I was shocked; I’m not his real, biological son? Maybe that’s why he never liked me, seemed prejudiced against me. I’m the wrong blood and can’t do a thing about it.

“The world went dark. I gave up. All I saw was a wall of night. I had failed. That was my bottom. I was drinking alone, a quart of whiskey a day. I dreamt of driving fast into oncoming traffic. I had an appointment with a doctor to check on the beginning stage of cirrhosis of my liver. I was heading toward my own death.”

One of Tommy’s favorite musical artists was Jelly Roll, a white, Tennessee-born rapper who put Tommy’s feelings into words:

All my friends are losers.

All of us are users,

There are no excuses, the game is so ruthless. The truth is the bottom is where we belong.

In Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Anne Case and Angus Deaton report a surprising finding: Although the United States had long been among the world leaders in extending its citizens’ life spans, since the turn of the 21st century, there has been an unexpected rise in premature deaths of white people in the prime of life, ages 45 to 54. The main causes are death by drug overdose, suicide, or alcoholic liver disease, which together claimed the lives of 600,000 people between 1999 and 2017. Especially hard hit have been white, blue-collar men without a bachelor’s degree.

Such men were not dying in heroic wars, battling fierce storms at sea, or toiling in coal mines. One by one, they were—and are—dying in solitary shame. In the obituary section of the Appalachian News-Express, I began to notice death notices showing young faces, sometimes listing young ages, but nearly always omitting the cause of death.

Tommy could name a number of local suicides. “The younger brother of a fifth-grade friend of mine shot another and then himself in the head. One guy drove drunk into a tree. My own brother Scott drove drunk off the road, and I believe that was a suicide. At one point, you could have almost counted me.”

Tommy remembers reading Christian Picciolini’s White American Youth: My Descent Into America’s Most Violent Hate Movement—And How I Got Out, the autobiography of a boy who was converted by a neo-Nazi. Picciolini was 14, smoking pot with a pal in a Chicago back alley, he writes, when a man in a muscle car drove up, stopped, and got out. The friend fled, but the man confronted the young Picciolini, took the joint out of his mouth, and said, “Don’t you know that’s exactly what the communists and Jews want you to do, so they can keep you docile?” By 16, now clean of drugs and with a purpose, Picciolini had become the leader of a group of Chicago-area skinheads, which he then merged with the yet more violent white supremacist Hammerskins.

“If I had been 14 and smoking in an alley and a man showed interest in me,” Tommy mused, “what if he dressed in camo, wore his ball cap back to front, and took me in? What if I began spending time at his house to get out of mine? And if my dad was beating me hard, and my parents were drinking, and I felt like they didn’t really know me or care? I ask myself: What would have happened? I could have felt the guy in the muscle car really cared about me.

“And what if that guy told me, ‘Your dad lost his job at the lumber mill because immigrants were coming in, or because a Jew closed it down’? I might have said, ‘Oh yeah,’” Tommy continued. “Or when I was going out with Missy [a mixed-race girl whom he invited to senior prom], what if he’d said, ‘Missy dumped you for that other guy. Black girls do that’? I might have said, ‘Oh yeah.’ Or when I flunked out of Clinch Valley community college and I couldn’t go home—my stepdad had converted my bedroom into his hobby room to make fishing lures—the man could have said, ‘Colleges are run by commies.’ I might have said, ‘Oh yeah.’”

In these ways, Tommy speculated, an extremist might offer recruits a raft of imagined villains onto whom to project blame and relieve the pain of shame. David Maynard had focused on a missing national narrative that might protect poor whites from the shame of failing to achieve the American Dream. Tommy was focused on something else: the shamed person’s vulnerability to those offering to blame a world of “outside” enemies.