The Unflinching Courage of Taylor Cadle

Melissa Turnage approached the 12-year-old girl with the imposing affect of a cop: arms crossed, lips pursed, badge visible, tone skeptical.

“So, you don’t know how many times this has happened this week?”

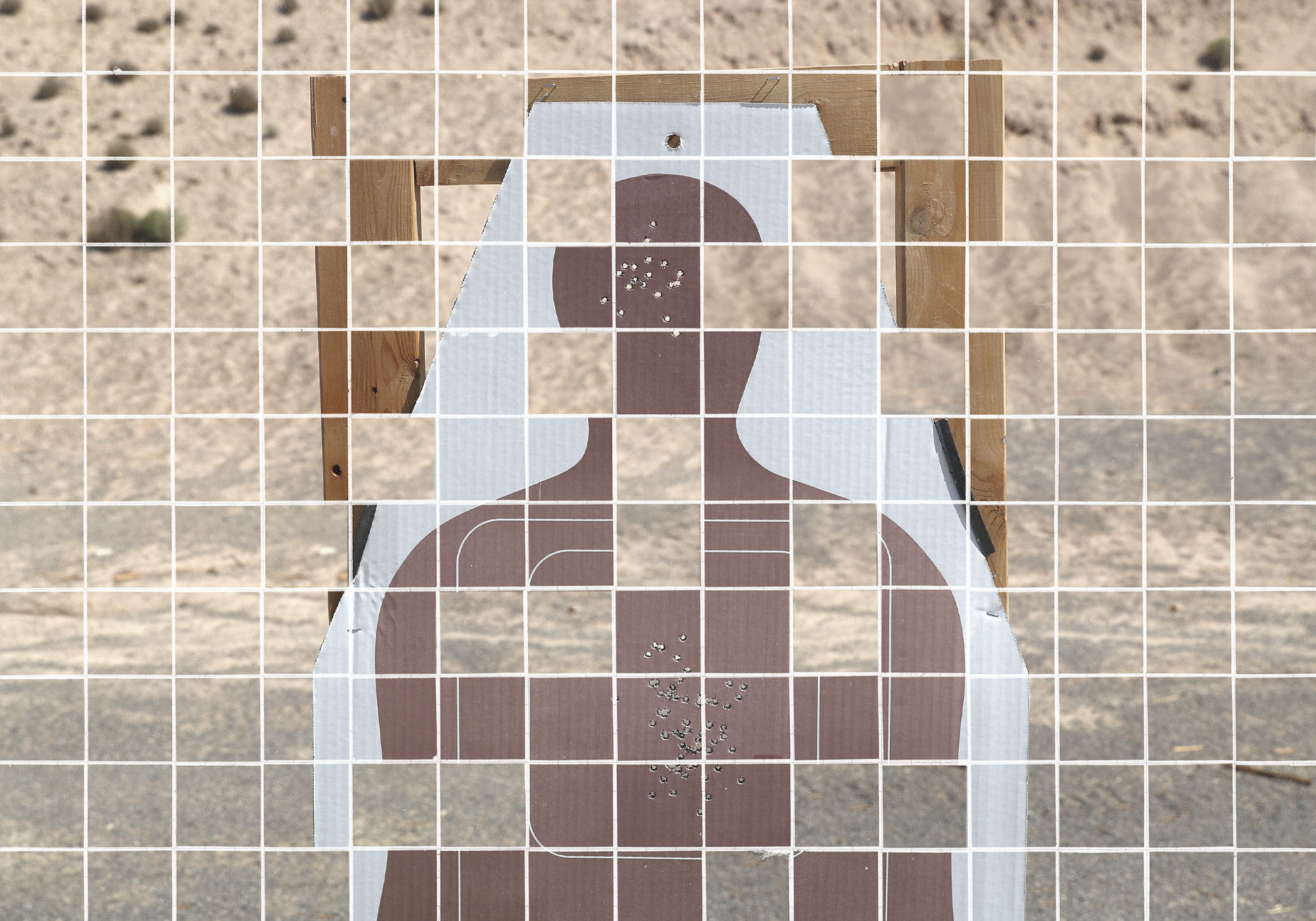

Taylor Cadle slouched on a couch, staring at her lap and picking at her nails. That morning, in the summer of 2016, she had gotten into a fight with her adoptive parents when they took away her phone on the ride to church, on the outskirts of Tampa, Florida. A minister’s wife, noticing Taylor’s tear-stained face, pulled her into an office to ask what was going on. Taylor hadn’t been planning to tell her everything, but it all came spilling out. The minister called the police, and now Turnage, a detective with the Polk County Sheriff’s Office, was standing before her.

Taylor spoke tentatively, in barely more than a whisper, as she told Turnage in a recorded interview that her adoptive father, Henry Cadle, had been sexually assaulting her for years. The inappropriate touching had started when she was 9 years old, shortly after Henry and Lisa, Taylor’s great uncle and his wife, had adopted her. Over time, the abuse escalated. Now, he assaulted her “anytime he gets the chance,” she said. She didn’t like going with him on errands because it happened then, on the side of a quiet road that cut through a swamp. Standing outside the car, he would put his privates inside of her privates, she told Turnage. Taylor couldn’t say how many times he had raped her, but it had happened just the night before. He did it whenever they drove to get milk, too, which was three times a week.

“That’s a lot of driving,” Turnage said.

Taylor said nothing.

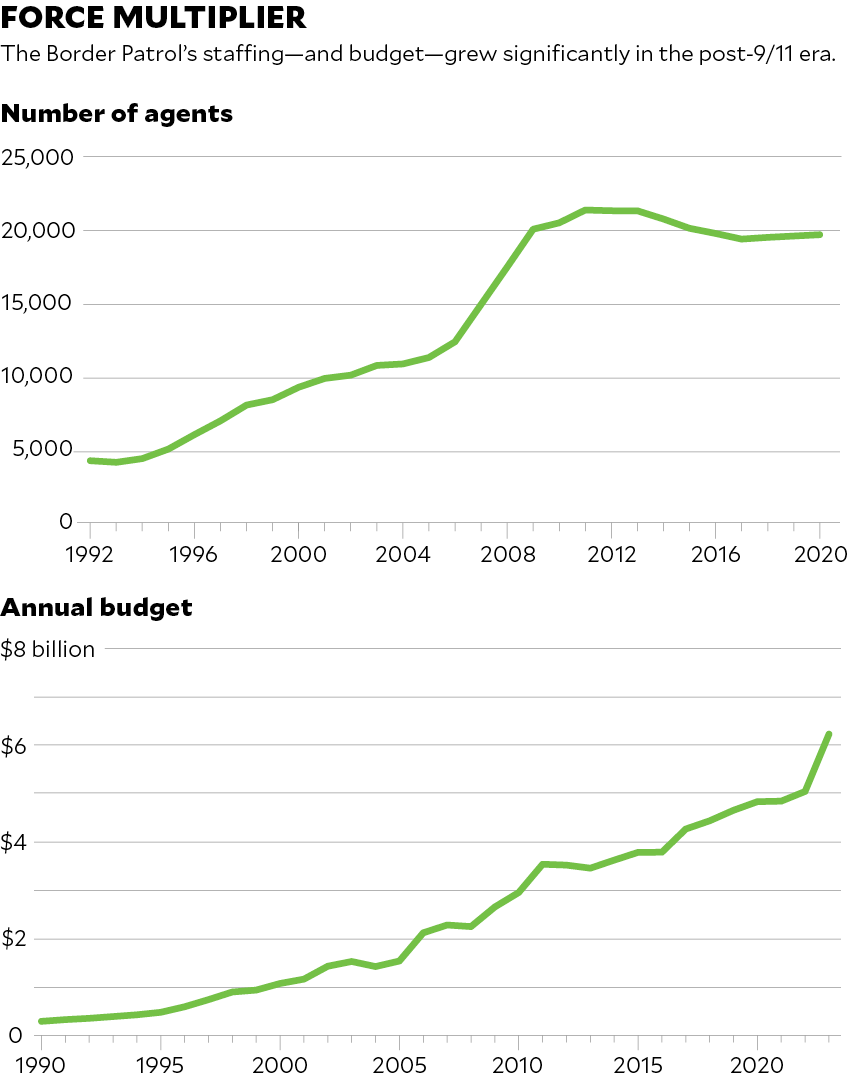

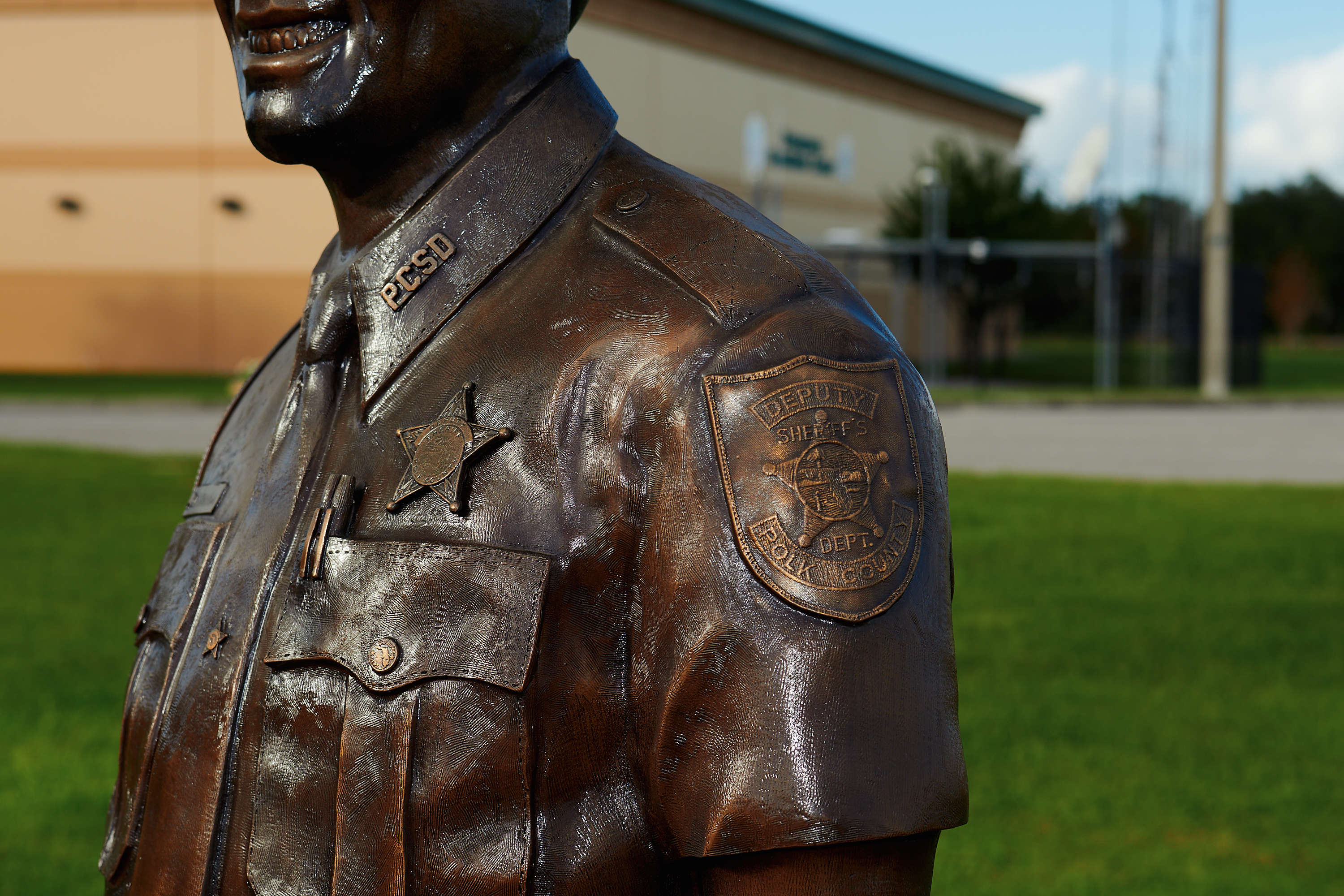

Turnage was embarking on the type of investigation that her boss, Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd, had made a core mission of his agency. Judd is a beloved figure in Polk County, where he has served as sheriff for the past two decades and was just reelected to his sixth term. Known for his tough-on-crime rhetoric and social media presence, Judd gives a near-daily “morning briefing” to his 700,000 TikTok followers, holding up mugshots of suspects, telling the stories of crimes they allegedly committed—from stealing baby formula to driving drunk—and welcoming them to jail, which he calls “Grady Judd’s Bed & Breakfast.” Fans buy Grady Judd bobbleheads, Grady Judd mugs, and sweatshirts reading “God Guns and Grady Judd.”

An old joke that has been repeated by Judd himself is that the most dangerous place in Polk County is between Judd and a camera. He’s a regular guest on Fox News, where he shares his outspoken views about subjects ranging from the dangers of undocumented immigrants to the peril of looters after hurricanes, and where the stories in Judd’s TikTok posts often find a national audience.

But he claims his top priority is protecting children from sexual predators. The county’s deputies have traveled to faraway places—from Colorado to Guatemala—to extradite men accused of victimizing children in Polk County. “If you think that you’re going to physically, sexually, or emotionally abuse a child and I’m not going to get in there and protect them, you’re making a big mistake,” he told MSNBC in 2015. In 2020, President Donald Trump appointed Judd to a federal council overseeing all programs related to juvenile delinquency, and missing and exploited children.

One might think that someone accused of the crimes Henry Cadle was accused of would be a prime target for the Polk County Sheriff’s Office. But when Turnage spoke with him, on a patio outside the church, she kept the interview brief and light. Henry, who was 57, spoke about his relationship with Taylor with a breezy confidence. She had anger issues and could be difficult—traits he attributed to her rocky upbringing—but he loved her to death. “Does she have dad wrapped around her finger? Yes. Everybody will tell you that,” Henry said.

Rather than asking him if he had sexually abused Taylor, Turnage floated a theory: “Basically, Taylor, I guess, has made up these allegations, okay? That you have been sexually abusing her.”

Henry brimmed with righteous indignation. “Why in the heck she would conjure up something like this about me, I don’t know. Only thing I’ve ever did with that kid is loved her.”

To hear a clip from Detective Melissa Turnage’s interview with Henry Cadle, listen below. A transcript for this audio can be found here.

Lisa Cadle was also dumbfounded by the allegations against her husband. Taylor adored Henry, Lisa told Turnage, and always begged to go with him on errands. She was quick to point out that Taylor was “mouthy” and “has been known to say things.” Turnage assured Lisa that kids had a way of making unfounded accusations “when things don’t go the way that they want it to.”

“Back when we were younger, it was, you know, ‘We’ll call [the Department of Children and Families] and say you abused me,’” Turnage said. “Now it’s, ‘We get sexually abused.’”

By the time Turnage spoke to Taylor again, later that afternoon, her skepticism sounded palpable. Turnage focused on one particular inconsistency: whether Taylor actually liked going for rides with Henry. “If you’re mad because you got your phone taken away, let’s say that now and be done with it,” she said in the recorded interview. “Because I have three stories that say you like to be with your dad, you’re daddy’s little girl, you love to go with him because you like to get out of the house.”

Taylor went silent. By necessity, she had developed a keen sense of the unsaid moods and whims of the adults around her. She had done the mental math when she joined Henry on the car ride the night before to visit his sister in the hospital. Taylor thought the somber occasion would keep her safe. But after the hospital and a quick stop at Taco Bell, Henry pulled into the Handy gas station and came out with a box of condoms stuffed into his front pocket, and she knew she had miscalculated.

Now, faced with an irritated deputy, Taylor realized she miscalculated again: She assumed the police would believe her.

“They’re going to pull you from your mom and your brother, and you’re going to have to go back into foster care.”

“What’s going on, Taylor?” Turnage asked. “Because you understand, if your dad goes to jail, he doesn’t come back.” There would be other consequences too, Turnage said. Her dad’s mower repair business would shut down. Her mom would lose the car while police checked it for DNA. She wouldn’t get the shoes she wanted, or the braces she needed. “They’re going to pull you from your mom and your brother, and you’re going to have to go back into foster care,” Turnage said.

A moment passed, and then another. Finally, in a small, strained voice, Taylor said, “Everything I told you earlier is not a lie.”

With that, Turnage told Taylor that she was going to the regional hospital “to have a sexual assault kit done.” Taylor didn’t know what that was.

To hear a clip from Detective Melissa Turnage’s interview with Taylor Cadle, listen below. A transcript for this audio can be found here.

Later that night, she slipped her arms through the sleeves of a too-big hospital gown and gingerly placed her feet into the stirrups. She shivered under the bright, fluorescent lights, nauseated from hunger and exhaustion. Although a doctor had walked her through what the examination would entail, Taylor was still shocked by the cold, hard metal thing that she later learned was called a speculum. As the doctor took one swab, and then another, and then another, Taylor clenched the side of the hospital bed, knuckles white, tears streaming down her cheeks.

Now 21 years old, Taylor has the same long hair and slight frame that she had when she was 12, but she no longer holds herself like she’s trying to make herself small. When we first met her in person, at an Airbnb for an interview in front of cameras and lights, she walked in as if she did this all the time, deftly setting her then-8-month-old daughter up for a nap in the bedroom before speaking, for nearly five hours straight, with the self-assurance and confidence of someone much older. She has a tattoo of the birthday of her son, who is 3 years old, in roman numerals on her left forearm, a nose ring, and dyed black hair—all decisions, she notes with a trace of pride, that she made despite Lisa’s disapproval soon after she turned 18.

But perhaps the biggest act of defiance is that she has decided to speak publicly about what happened to her when she was 12. Asked if she wanted to use a pseudonym or just part of her name, she said no—she wants to use her full name, and she wants to share her whole story.

The way Taylor was treated—as a victim, but also as a suspect—flies in the face of best practices in handling sexual assault investigations. Her case isn’t an isolated one. In a multiyear investigation, the Center for Investigative Reporting identified hundreds of similar cases across the country in which police criminalized the very people reporting sexual assault.

“I think from the beginning—from our first interview—she had already had her mind made up about me. She made me feel like the monster.”

Armed with hours of recorded interviews, police reports and state records stemming from her report eight years ago, Taylor simmers with fury about how Turnage handled her allegation. “I think from the beginning—from our first interview—she had already had her mind made up about me,” she says. “She made me feel like the monster.”

But when she thinks about herself that night on the hospital bed, Taylor crumples. In court records from her case is a photo from the sexual assault exam, her 12-year-old self looking up at the camera from the hospital bed.

“Little me,” she said recently, her voice catching as she stared into her own eyes. “Broken inside. With a look of ‘Are you listening yet? Do you believe me yet?’”

Taylor’s earliest memories are of parenting her younger siblings. As a child, she gave them baths, made them food, and tucked them into bed. She was her mom’s “best friend,” she says. Taylor served as a lookout when her mom would steal drugs from her boyfriend, and she knew to pee in a cup and leave it under the bathroom sink when the probation officer came by.

“I worried about everything,” she says. “I stressed about everything that, quite honestly, a child should never have to worry about.”

When she was 7, amid drug use and violence at home, the Department of Children and Families placed Taylor into foster care, according to agency records. “I wasn’t relieved as much as I probably should’ve,” Taylor says. “It was still hard because being a child, and all you ever want is your mom.”

For the next year and a half, she bounced from foster home to foster home. It was a “scary, confusing” time, Taylor says. She desperately wanted to be reconnected with her parents and siblings, who had been placed in other homes. Her birth father had been a source of normalcy and stability before she was taken into state custody, but his drug use, too, precluded him from being cleared by DCF.

Taylor’s tendency to assert control, key to her survival as a young child, became a liability that was pathologized in reports and case notes. Foster parents and case workers labeled her “defiant” and “bossy.” She had tantrums often and was accused of lying about little things, like stealing peanuts from the grocery store and taking another child’s phone. “Lying seems to have been a defense mechanism that has worked in the past to keep her safe,” noted one social worker in an assessment.

When Taylor was 8, Lisa and Henry “surfaced,” as it was described in a case manager’s notes. They were relatives of her birth father—Taylor didn’t really remember them—and were excited about adopting Taylor. They said their 6-year-old adoptive son wanted a big sister.

Taylor soon began making regular visits to the Cadles’ home in Polk City, partway between Tampa and Orlando. The family lived in a small mobile home surrounded by pastures and swamps, 45 minutes from the nearest Walmart. Taylor had reservations, telling staffers on her case that she was wary of moving again and scared of being rejected.

But she had little say in the matter: Two days before Taylor’s ninth birthday, her adoption was finalized. The Cadles had taken Taylor on shopping sprees and trips to SeaWorld during her weekend visits, but after the adoption, the family dynamic shifted. Discipline was harsh: Lisa was quick to smack Taylor across the mouth if she talked back, Taylor says, “but when Henry got ahold of us, it was a whole different story.” She still remembers having to wear jeans to school one sweltering day because his beating with a cooking spoon on her calves had left welts.

She felt claustrophobic in the cramped home, and begged Henry and Lisa to let her get out of the house. Lisa and her adoptive brother were homebodies, but Henry also liked to go for drives, so she went along.

It was on these long drives that he would assault Taylor, sometimes several times in a week, she says. A turnoff on an isolated backroad became his go-to spot. Across from a wilderness preserve, next to a cell tower access road, he would pull over.

Taylor tried to predict and avoid situations where he would see opportunity for abuse. “If I knew we were taking a back road or anything of the sort, I didn’t want to go because I knew what would happen,” she says. “I had to be on all 10 toes, 24-7.”

Fearful of going back to foster care, Taylor didn’t tell any authority figures—until that Sunday morning in July 2016, when she met Detective Melissa Turnage.

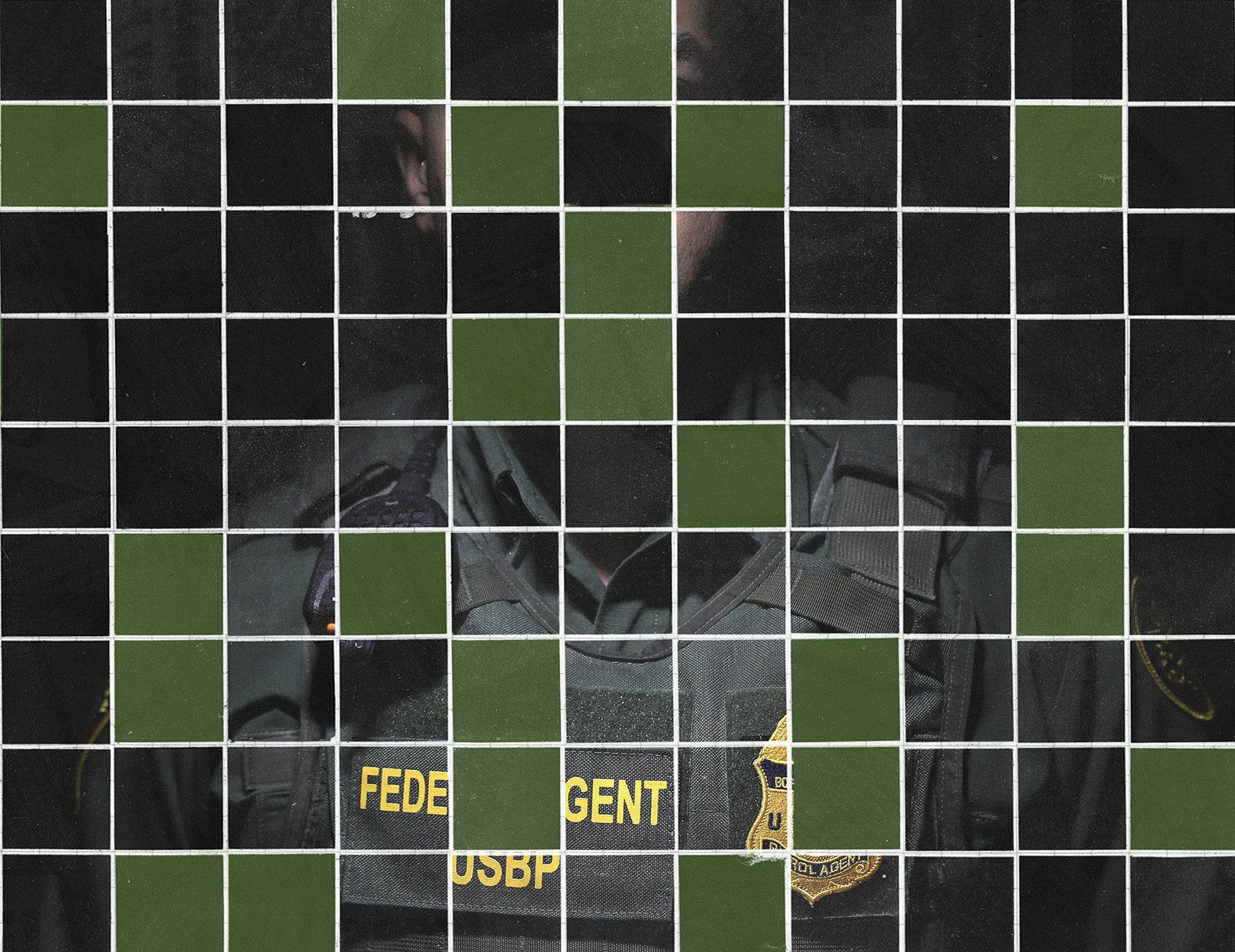

Turnage was in her ninth year with the Polk County Sheriff’s Office and considered a model deputy, according to her performance reviews. Turnage’s “integrity is above reproach,” wrote her supervisor in the spring of 2015.

But mistakes quickly followed. In November 2015, during an interview with a man suspected of sexually assaulting a child, Turnage failed to read the suspect a key part of his Miranda rights—an omission that resulted in the suppression of the suspect’s confession. Turnage was suspended for eight hours, according to department records.

The following month, Turnage interviewed children who alleged their father was raping them, and then left for Christmas vacation without bringing the suspect in for questioning or updating her supervisors on the status of the case. While she was away, her colleagues found out about the seriousness of the accusations and immediately arrested the suspect. “Your decision to not complete this investigation or advise me of the interview results is inexcusable,” her supervisor wrote in a letter that year. “Disclosures made by children in this case must be acted upon immediately if the investigation allows for it.”

By August 2016, Turnage was in the middle of her investigation into Taylor’s case, and she wanted to do a “clarification interview” with Taylor—at a noisy truck stop parking lot. As cars whizzed by on the highway, Taylor thought it was an odd location to meet. Perhaps, she thought, it was out of convenience—the midpoint between the sheriff’s office and Tampa, where Taylor had been crashing with Henry’s adult daughter ever since that day in church.

Leaning against her car, Turnage said she’d gone through Taylor’s phone records, and saw that she was texting continuously at the time she said she was raped. Taylor explained that she used her phone as a barrier so Henry wouldn’t talk to her during the abuse. If that was the case, asked Turnage, why didn’t Taylor alert someone to the abuse while it was occurring? Taylor said she didn’t know.

Turnage looked for Henry on surveillance footage from the gas station where he supposedly bought condoms, she told Taylor, but he wasn’t there. Taylor had been quiet, if skeptical, in her interactions with Turnage up to this point, but now her temper flared. Henry was there, Taylor said, and it wasn’t her fault if Turnage couldn’t find evidence. “I am telling the truth,” she insisted. She stormed to her sister’s car and locked herself inside.

Turnage concluded that there wasn’t evidence to support a criminal charge against Henry. The surveillance footage turned up nothing. The car hadn’t shown any evidence of bodily fluids. The hospital exam hadn’t found evidence of trauma. Taylor had said the abuse happened near a pile of tires on a quiet road near the Cadles’ home, but Turnage only found a busy road with no tire pile in sight.

Sexual assault investigations involve sensitive gathering of information by trained professionals who understand the dynamics of abuse—ideally in neutral, safe, quiet settings with no distractions, said Jerri Sites, an expert in child abuse investigations who facilitates trainings on best practices. After listening to recordings of Turnage’s interviews, Sites concluded that they sounded like interrogations by a biased detective. “It seemed as though she was trying to pressure the child to recant,” she said. “It was really, really hard to listen to.”

Turnage didn’t bring the same skepticism to her interviews with Lisa and Henry. Her interview with Henry outside the church—the only time he was officially questioned—lasted just 20 minutes. During this time, he made a troubling admission. When asked if he would take a polygraph test, Henry declined. “I’ve had sex with a lot of people in the shower with my eyes closed, if you know what I mean,” he explained. “I’m a man.”

To hear a clip from Detective Melissa Turnage’s interview with Henry Cadle, listen below. A transcript for this audio can be found here.

If Turnage was concerned about Henry acknowledging he had sexual thoughts about his adoptive daughter, she didn’t show it. “Daydreaming about it and answering questions in reference to the allegations are two totally different things,” she told him.

There were other missed opportunities during the investigation. There is no indication that Turnage asked for Henry to be forensically examined, even though the suspect’s body sometimes provides more evidence than the victim’s. When Turnage went looking for the remote road with the pile of tires, a location that Taylor described with the uncertainty of a 12-year-old who doesn’t drive, she never asked Taylor to join her to show her where it was.

Finally, Turnage erred in gathering a key piece of evidence: video of Henry buying condoms at a gas station. Surveillance footage from Henry and Taylor’s previous stop, Taco Bell, showed them leaving at 7:43 p.m. They should have arrived at the gas station about a half hour later, but confoundingly, Turnage requested footage starting 45 minutes later. In those missing 15 minutes, Henry likely would have already come and gone.

Turnage’s investigation came to a head after five months, in December 2016. She spoke with Taylor on the porch outside the Cadles’ home to deliver the news: The final results from the rape kit had come back, and there was no evidence of Henry’s DNA. “I’m not saying you’re lying,” Turnage told Taylor. “I just want to know why, if everything you said is true, why am I not finding anything?”

Taylor’s voice came out as a whimper. “I don’t know,” she said. “I swear on my life it happened.”

In fact, rape kits often don’t show evidence of abusers’ DNA, especially when more than 24 hours have passed since the abuse occurred, or when a condom was used—both of which applied in Taylor’s case.

“If it happened, there would be—there would be DNA found,” Turnage said. “And we didn’t find anything.”

If Taylor lived in another county, perhaps her case would have ended there: allegations made, no corroborating evidence found, no charge against the alleged abuser. But in Polk County, no wrongdoing is too small for a consequence. Sheriff Judd often quotes a phrase he learned from his late father: “Right is right, and wrong is never right.”

“Polk County has a very pro-arrest outlook,” said Joel Dempsey, a detective with the office until 2018. “If charges are deemed justifiable, then [suspects] are likely going to be charged.”

Inside the house, Turnage told Lisa that the sheriff’s office planned to move forward with a criminal charge against Taylor for lying to a law enforcement officer about a felony. Lisa was on board. “We know she’s mouthy, and she tries to act older than what she is,” she said.

Afterward, Turnage spoke with Taylor’s adoptive sister about what Taylor’s life would look like if she were sent to the juvenile detention center.

“You’re in your pretty little blue jumpsuit, with your little flip flops, and you’re housed with everybody else,” said Turnage. “She would come in and look like the pretty girl.”

Hearing bits and pieces of the conversation through the sliding porch door, Taylor had the distinct feeling that she was drowning.

Two days after meeting with Taylor at the Cadles’ home, Turnage filed an affidavit. The real crime wasn’t the alleged sexual abuse—it was that Taylor had given false information to a law enforcement officer, a first-degree misdemeanor. The victim of this crime, according to the affidavit, was the Polk County Sheriff’s Office.

Taylor is one of hundreds of victims alleging sexual assault who have been charged with false reporting nationwide. No federal agency tracks the prevalence of false-reporting charges, but over a multiyear investigation, documented in the Emmy Award–winning film Victim/Suspect, the Center for Investigative Reporting (which produces Mother Jones and Reveal) identified more than 230 cases of reporting victims charged with crimes, originating from nearly every state.

Most criminal justice experts estimate that 2 to 8 percent of sexual assault allegations are actually false. But law enforcement officers tend to assume the rate of false reporting is much higher—in part because police officers don’t always receive training on how trauma can affect memory or behavior.

Through dozens of freedom of information requests, we amassed a first-of-its-kind trove of audio and video evidence documenting the police practice of criminalizing those who report sexual assault. We found examples of police officers lying, deploying interrogation techniques meant for criminal suspects that, when used on unsuspecting, traumatized people, can undercut their credibility and even cause them to recant. Of 52 cases analyzed closely, nearly two-thirds resulted in the alleged victim recanting. In nine cases, the recantation was the only evidence cited by police.

Most cases centered on adults accusing other adults, largely because juvenile arrests are not usually matters of public record. But a few examples emerged of children being charged.

In 2008, after an 11-year-old girl in Washington, DC, twice reported being sexually assaulted, she was charged with making a false report. But, as a Washington Post investigation detailed, detectives didn’t follow basic guidelines for how to treat victims of sexual assault. They lied to her, saying there was evidence contradicting her account, despite two medical reports confirming that she suffered genital injuries. Still, police and prosecutors wanted her punished for fabricating her report. After a plea deal, she was taken in as a ward of the District of Columbia, and spent more than two years in residential mental health facilities.

In 2014, a 12-year-old Indiana girl told police that a boy forced her to have sex with him. Phone records revealed that the boy apologized to her after the incident. Still, a detective challenged her use of the word “force”—she told the boy no, she said in a recorded police interview, but he didn’t hold her down. The detective sent the case to prosecutors, who charged her with lying.

We also learned of a 12-year-old girl in Polk County, Florida: Taylor. Last year, we sent Taylor a message on Facebook, explaining our investigation into police turning the tables on victims and asking if she’d like to talk about what happened to her. She immediately responded: “I’m sorry I’m shocked,” she wrote. “Is this real?” Within an hour, she called to talk.

There were few public records tied to the case due to confidentiality laws meant to protect children. So Taylor wrote records requests, signed release forms, and notarized documents to obtain case files and recordings from the sheriff’s office, the juvenile court, the circuit court, the Department of Children and Families, and the Department of Juvenile Justice. Then she shared them with us.

The culture of consequences that permeates the Polk County Sheriff’s Office applies to kids as well as adults. The same year as Taylor’s case, for example, the sheriff’s office accused an 11-year-old girl of lying about an attempted abduction. She, too, was charged with filing a false police report, which the sheriff’s office wrote on Facebook would “help re-enforce the lesson” after she wasted police resources.

Between 2019 and 2023, more children in Polk County were charged with misdemeanor obstruction of justice—an umbrella category that includes false reporting—than in any other Florida county. Children in Polk were twice as likely to face the charge than children in the state overall, according to an analysis of data from Florida’s Department of Juvenile Justice.

Such charges may be intended to make the community safer, but they can do the opposite, said Sites, the child abuse expert. “It’s hard enough to come forward in the first place,” she said, “and if the community feels that someone might be charged, people aren’t going to come forward.” Even in cases when a child isn’t telling the truth, she said, the response should be support services to help a child understand that it’s not okay to lie—but also efforts to understand why they did so in the first place. “Something is not right if somebody’s going to go to those lengths to falsely accuse somebody,” she said.

Turnage’s conclusion that Taylor was lying had bigger ramifications: DCF was supposed to conduct its own investigation, but it closed the case on the grounds that Turnage hadn’t found evidence of abuse.

The agency also appears to have used Taylor’s years of records against her. DCF records reference two allegations of sexual abuse before 2016. When Taylor was 5, her mother’s friend was arrested for sexually assaulting Taylor. And when Taylor was 11, DCF investigated a report made by her school that her gym teacher had touched her inappropriately. Taylor didn’t report the incident herself—rather, it was a rumor started by a group of girls. Taylor denied the rumor, and the case was closed with no indicators of abuse, according to the report.

“It’s hard enough to come forward in the first place, and if the community feels that someone might be charged, people aren’t going to come forward.”

But by 2016, the details didn’t seem to matter to DCF. In its report closing the investigation into Henry’s alleged abuse, the agency noted, “There is a pattern of...reports involving Taylor with allegations of sexual abuse and being touched by other males.”

Richard Wexler, who leads the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, said that child protective services agencies often give adoptive families the benefit of the doubt. “Whenever a child welfare agency investigates abuse in foster care or in an adoptive home it is, in effect, investigating itself—because they put the child there in the first place,” he said. “That creates an enormous incentive to see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil and write no evil in the casefile.”

Remarkably, the same day Turnage filed the affidavit accusing Taylor of lying, she received a disciplinary letter from a lieutenant regarding another case. After investigating the sexual assault of a minor, Turnage had arrested the wrong person. A video of the assault showed the suspect had visible tattoos, but the man she detained had none. “It is imperative that as a detective you look at the totality of the circumstances and all evidence present in developing probable cause to make an arrest,” the letter read. It concluded, “You are a valued member of this agency and I am confident this will not recur.”

After four months with her adoptive sister, Taylor moved back in with the Cadles. Henry was friendly with her, full of smiles. “It was like a sticky sweet,” she says. He didn’t ask about the past four months or comment on the investigation—instead, he acted as if nothing had happened.

Taylor kept to herself, holing up in her room. She wrote about her dreams in her journal, like the one where she was trapped with an alligator in a locked room. Sometimes, she’d get so upset that she’d crouch on the floor, rocking back and forth, pulling out fistfuls of hair.

She vacillated between depression, fury, and exhaustion. She worried that if she stuck to her story in the face of her criminal charge, she would be sent to juvie. “I was basically like, I have no other choice,” she says. “I have to recant my story.”

In a meeting in February 2017 with Lisa, Henry, and her probation officer, Taylor said that she lied about being raped because she was mad about her cellphone being taken away. A report from the meeting reads, “Father extremely hurt by youth’s actions but forgives her.”

Three months later, on the way to the Polk County Courthouse for her arraignment, Lisa told her to “take it on the chin,” Taylor remembers. The state had offered Taylor a deal: If she pleaded guilty to her charge and completed the terms of her probation, the charge would be dismissed. Lisa and Taylor both signed a document agreeing for Taylor to “freely and voluntarily” waive her right to a lawyer and represent herself. She pleaded guilty to giving false information to a law enforcement officer.

Judge Mark Hofstad ordered probation, and signed an order for the terms: 15 hours of community service, a 7 p.m. curfew, and limits on leaving a tri-county area without permission from Taylor’s probation officer.

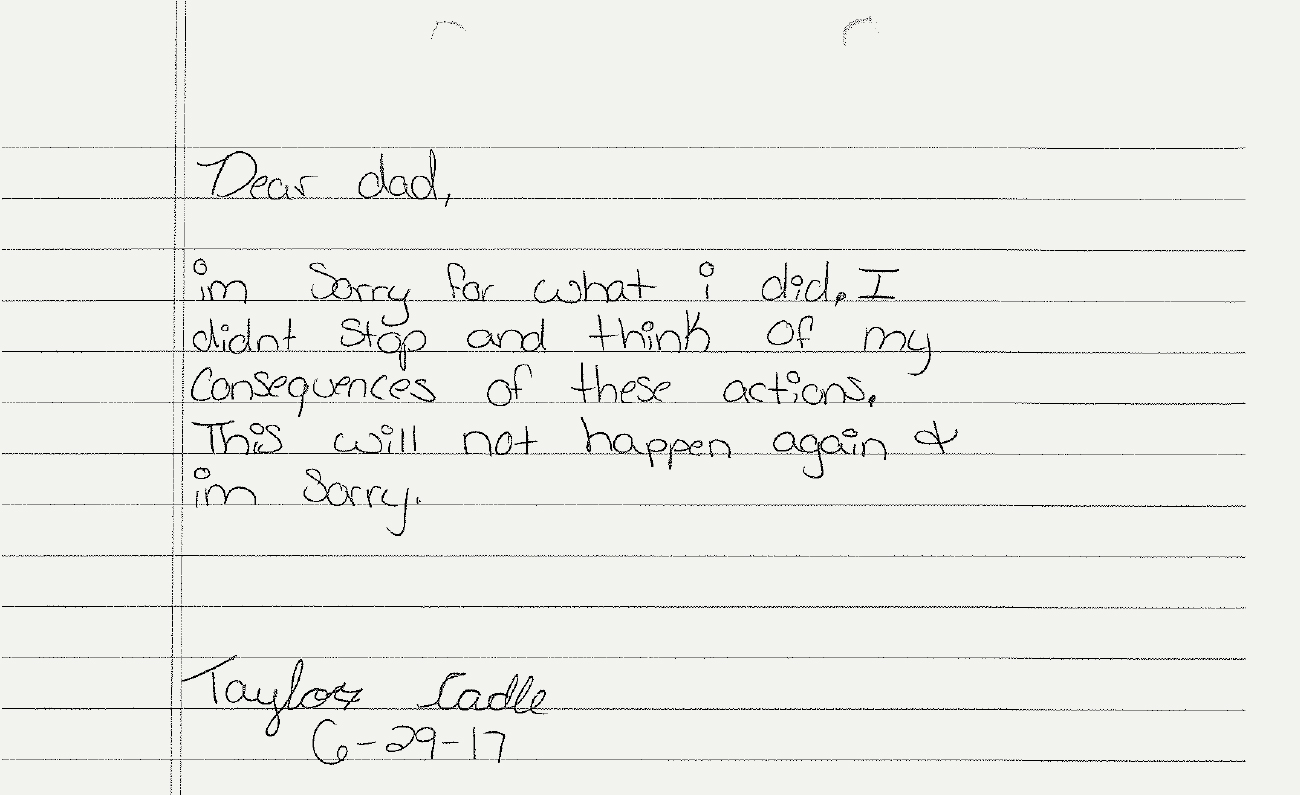

Taylor also had to write two apology letters: one to an unspecified officer, and the second to Henry. Without giving the words any thought, she scribbled in her journal and tore the pages out.

“Dear dad,

im sorry for what i did. I didn’t stop and think of my consequences of these actions. This will not happen again + im sorry.”

One evening in July 2017, a month after writing the apology letters, Taylor accompanied Henry to pick up a mower that needed repairs.

The sun was setting as they made their way home, and Henry pulled into a Dollar General to get something to drink. Taylor waited in the truck—now that she was 13, she could finally sit in front. As Henry walked out of the store, she saw that he was empty-handed, but his front pocket was bulging.

She realized several things simultaneously. The first was that he had bought condoms—which was confirmed when he got into the car and tossed a Lifestyles box in her lap. The second: She had thought that Henry would be too scared to abuse her again after all the scrutiny, but he had been emboldened. The third: She didn’t have anyone to call for help. The adults in her life—and the police—thought she was a liar.

Finally: She had to document what he did to her that night, so there would be no question about what had happened.

“I had to find the evidence for them,” she says. “Because if I didn’t find the evidence for them, I wasn’t too sure they would find it.”

As Henry drove, she made sure he could see that she was playing a game called Piano Tiles, tapping black piano keys as they floated across the screen. About 15 minutes into their drive, Taylor tilted the screen away from Henry for a moment and snapped a photo of the condom box.

Henry drove to the same spot as he had a year before, on the turnout of the quiet road that cut through the swamp. It was dusk outside, the road empty, the night quiet other than the chirping crickets and cows bellowing in a nearby pasture. As Henry walked around the back of the truck, Taylor recorded a six-second video panning to four crucial visuals: the radio clock reading 8:29 p.m., the back of Henry’s head, the condoms on the dashboard, and the view outside her window.

Then, she says, Henry unzipped his pants and ordered her to pull down hers. “You know what to do,” he said. Taylor’s Android allowed her to take photos by swiping up anywhere on the screen. When Henry told her to hurry up with her phone, she told him to wait a second—she was just closing applications. She swiped up again and again, silently snapping photos.

After it was all over, when he turned around to check for cars, she shoved the empty condom box under the seat. They began the drive home—AC pumping, pop music playing on the radio—and Taylor mentally collected more evidence: the white smear on the seat, the bushes where he threw a used tissue, the stretch of grass where he tossed unused condoms out the window as they drove.

Once home, Taylor told Lisa she was taking the dogs for a walk. Standing in the yard in the dark, she deliberated. She was terrified of calling the cops. If she wasn’t believed again, surely she’d face an even harsher punishment than the first time. But if she didn’t call the cops, nothing would change. The thought, on repeat: Am I going to do it?

She dialed 911.

Taylor describes the next few hours like scenes in a movie: the cars driving up, no lights or sirens, as Taylor had instructed, since Henry was sleeping. A cop’s flashlight through the backdoor. Taylor standing outside with an officer, showing the photos and video on her phone. The lights of cop cars bouncing off Henry’s vacant face as he was escorted through the yard in handcuffs. Taylor bawling after an officer asked her to go back to the godforsaken, freezing hospital in the middle of the night for another rape kit exam.

“I was fighting for my life, in a very quiet scream.”

At first, Henry denied any wrongdoing. “I don’t know what the hell—why is she doing this again?” he told Polk County Detective Joel Dempsey in a recorded interview. It was only when Dempsey showed Henry the photos that Henry admitted that the photos were, in fact, of him.

Henry continued to deflect blame in recorded calls from jail, insisting that he had been set up. “I was dealing with a venomous snake,” he told his sister. In another call, he insisted, “It’s not all my fault neither. Yes, I’m the adult, but it’s not all my fault.”

Two days after the assault, Taylor sat through a videotaped forensic interview at a child advocacy center—the same child advocacy center and the same case worker she spoke to the year before. She spoke with urgency as she explained the evidence she had collected, still convinced that, somehow, Henry would work his way out of this.

“I mean, I really hope that they actually, like, take the time to, like, actually investigate and to listen to my side of the story before they just want to accuse me of giving false information,” Taylor told the case worker. “I tried everything. I did everything I could do.”

Taylor Cadle’s 2017 forensic interview

Today, Taylor remembers this moment in vivid detail. “I was fighting for my life,” she says, “in a very quiet scream.”

The next day, Henry Cadle was charged with sexually assaulting Taylor.

“I don't remember any other case where the victim had the forethought or the intelligence to collect their own evidence and to be so thorough,” Dempsey said recently. “Just, unbelievable amount of presence of mind that she showed.”

Assistant State Attorney Joni Batie-McGrew, who approved the original false-reporting charge against Taylor, filed a motion to vacate Taylor’s probation and guilty plea. The information Taylor had provided to the police, the motion said, “has since been determined to be true.”

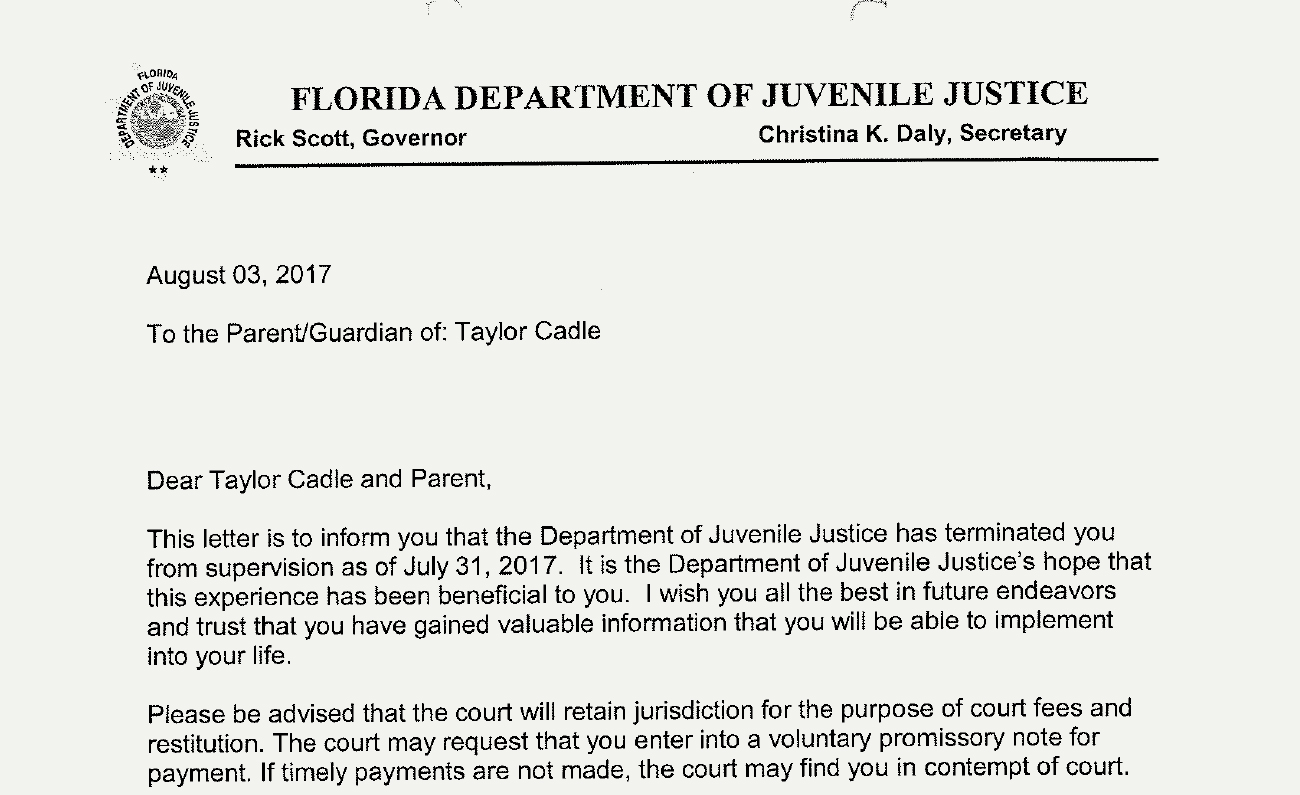

The Department of Juvenile Justice sent Taylor a letter terminating her supervision, adding that it was the department’s hope that the experience was beneficial to her.

In February 2019, Henry pleaded no contest to the sexual battery of a child. He was sentenced to 17 years in prison.

Taylor still lives in Polk County, just a half hour away from where she once lived with Lisa and Henry. She stays at home with her two kids—a 3-year-old boy and a 1-year-old girl—and the family’s massive pitbull mastiff while her fiancé works at an auto glass repair shop.

Motherhood comes naturally to Taylor. In the moments of chaos—when she’s trying to feed her baby and her toddler is climbing on her back and the dog is barking—she laughs. When her baby cries, she coos, “What’s wrong, girlie?” In her free time, Taylor vlogs about beauty and parenting in a way that’s refreshingly real, talking, for example, about how to wax your armpits or how dinner that night will be subs because the Walmart bread is getting stale.

In October, our interview with Taylor aired on PBS NewsHour. “Why punish me?” she said on camera, with an unflinching gaze. “What did I do for you to punish me?”

The video got millions of views on TikTok, and local and national publications picked up the story. Viewers flooded the comments sections of the Polk County Sheriff’s Office’s social media pages to demand justice for Taylor. But some of those comments mysteriously disappeared from view, prompting more outrage. Taylor decided to send Judd an email directly. She admired his work overall, she wrote, but she was outraged.

“I thought you guys were supposed to help? Not silence a victim.”

Judd has often said that the key to being a good sheriff is transparency with the public. One of his often-repeated phrases is: “If you mess up, then dress up, fess up, and fix it up.” But records show Henry Cadle’s arrest didn’t prompt any disciplinary action at the time. Judd has not responded to questions about the case publicly, or to Taylor.

Turnage didn’t respond to our attempts to reach her, and Judd’s office declined an interview. When we showed up at the sheriff’s office in August and asked to speak with Judd, we were told that a public information officer would come down to talk. Minutes later, we were told, she had been pulled into a meeting and didn’t know when she would be available. (A spokesperson told the Lakeland Ledger that the sheriff’s office wouldn’t speak to us because it “became clear they were not interested in accurately reporting an investigation that occurred in 2016.”)

Florida Senate Minority Leader Lauren Book, however, had more luck. A Democrat from Broward County, Book sponsored recent legislation requiring law enforcement to receive training in trauma-informed sexual assault investigations. After listening to audio of Turnage’s interviews that we shared with her, an incensed Book asked Judd for information about Taylor’s 2016 case.

In a letter to Book last month, Polk County Captain Dina Russell defended Turnage’s "thorough investigation” and doubled down on the same concerns with Taylor that Turnage had back in 2016: Taylor had said she didn’t like going on rides with Henry, but family members said otherwise. Henry wasn’t on the surveillance video buying condoms. Taylor was texting during the abuse, but, Russell wrote, “made no mention in her texts she was being abused.”

But after listening to a recording of an interview from the case, Russell acknowledged that Turnage’s approach didn’t meet the department’s standards. She sent Turnage a “letter of retraining” last month.

“Several of your questions and comments were inappropriate,” Russell wrote. “While your intent may have been to elicit the truth and gather essential information, referencing personal circumstances such as foster care or financial hardships can create an environment of discomfort, fear, mistrust is simply unacceptable.” The letter made no mention of the ramifications of these failures for Taylor, or the fact that Taylor was later deemed to be telling the truth.

The captain’s demands of Turnage were minimal: Within a week, she was required to complete an online course on interview and interrogation techniques. The captain’s conclusion echoed the disciplinary letter Turnage received in 2016, when she arrested the wrong suspect: “I am confident you will take the appropriate steps to prevent any similar events in the future.”

Turnage is still a detective, though she’s no longer in the special victims unit. Her latest performance review noted that she’s on track to become a sergeant.

Batie-McGrew, who prosecuted Taylor’s first case, also didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment. But the state attorney’s office said in an email that after Taylor was proven to be telling the truth, they made a policy change: They now require that the office be consulted before charging a juvenile who claims to be a victim of sexual abuse, according to Jacob Orr, the chief assistant state attorney for the 10th Judicial Circuit.

Since Taylor’s case, Orr said, the office has charged three other juveniles with falsely reporting sexual abuse. He said those cases included “irrefutable evidence proving the falsehood” of their claims, but he didn’t elaborate on how police were able to irrefutably prove that the children were not sexually abused.

For Taylor, three more children is far too many. “It should have stopped with me,” she says. “It shouldn’t have even gotten to me, but it should have stopped with me.”

Once in a while, Taylor drives on the quiet road through the swamp, past the spot where Henry abused her. It’s still hard, but having her kids in the backseat makes clear how much things have changed over the past seven years. She’s no longer a child being driven there against her will, bracing herself for the worst, preparing to crouch on the floorboard if anyone drives by.

Now, she is in the driver’s seat. “It’s a sense of relief, in a way,” she says. “I’m going past this spot because this is the route I chose to take.”

Melissa Lewis contributed data analysis.