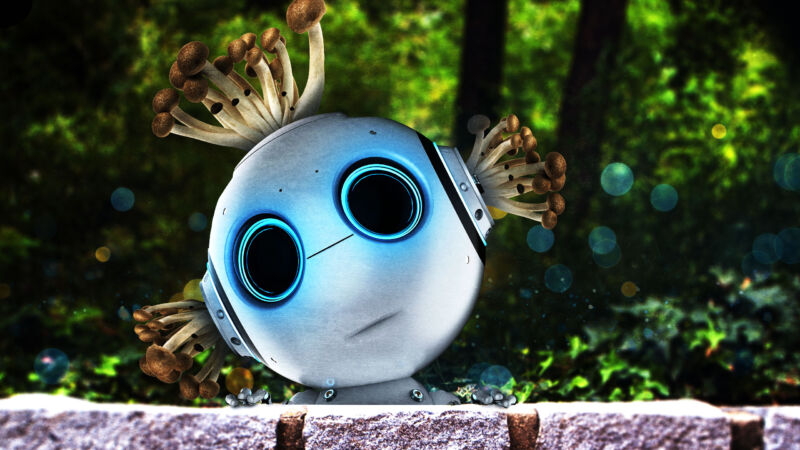

Fungi may not think, but they can communicate

Fungi can be enigmatic organisms. Mushrooms or other structures may be visible above the soil, but beneath lurks a complex network of filaments, or hyphae, known as the mycelium. It is even possible for fungi to communicate through the mycelium—despite having no brain.

Other brainless life-forms (such as slime molds) have surprising ways of navigating their surroundings and surviving through communication. Wanting to see whether fungi could recognize food in different arrangements, researchers from Tohoku University and Nagaoka College in Japan observed how the mycelial network of Phanerochaete velutina, a fungus that feeds off dead wood, grew on and around wood blocks arranged in different shapes.

The way the mycelial network spread out, along with its wood decay activity, differed based on the wood block arrangements. This suggests communication because the fungi appeared to find where the most nutrients were and grow in those areas.

© vnosokin