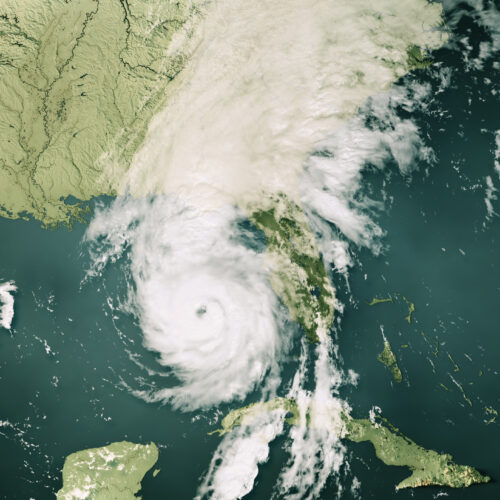

Climate change boosted Milton’s landfall strength from Category 2 to 3

As attempts to clean up after Hurricane Milton are beginning, scientists at the World Weather Attribution project have taken a quick look at whether climate change contributed to its destructive power. While the analysis is limited by the fact that not all the meteorological data is even available yet, by several measures, climate change made aspects of Milton significantly more likely.

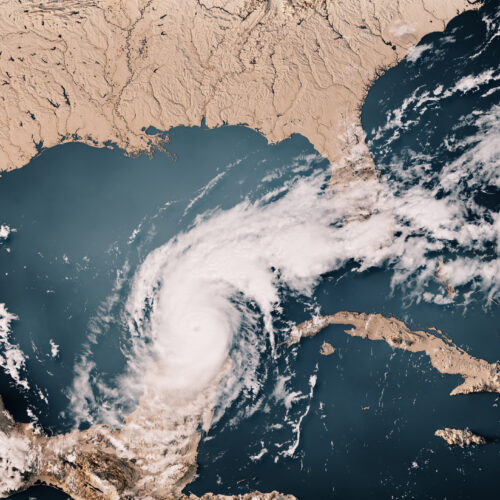

This isn't a huge surprise, given that Milton traveled across the same exceptionally warm Gulf of Mexico that Helene had recently transited. But the analysis does produce one striking result: Milton would have been a Category 2 storm at landfall if climate change weren't boosting its strength.

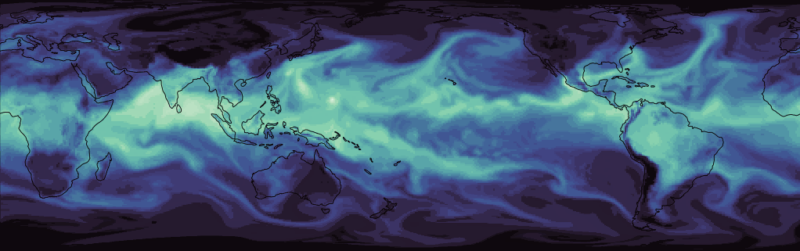

From the oceans to the skies

Hurricanes strengthen while over warm ocean waters, and climate change has been slowly cranking up the heat content of the oceans. But it's important to recognize that the slow warming is an average, and that can include some localized extreme events. This year has seen lots of ocean temperature records set in the Atlantic basin, and that seems to be true in the Gulf of Mexico as well. The researchers note that a different rapid analysis released earlier this week showed that the ocean temperatures—which had boosted Milton to a Category 5 storm during its time in the Gulf—were between 400 and 800 times more likely to exist thanks to climate change.

© Frank Ramspott