Nearly three years since launch, Webb is a hit among astronomers

From its halo-like orbit nearly a million miles from Earth, the James Webb Space Telescope is seeing farther than human eyes have ever seen.

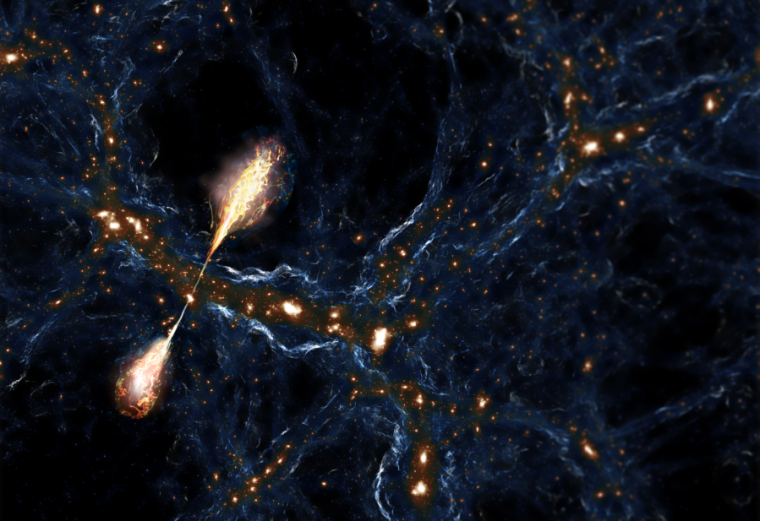

In May, astronomers announced that Webb detected the most distant galaxy found so far, a fuzzy blob of red light that we see as it existed just 290 million years after the Big Bang. Light from this galaxy, several hundreds of millions of times the mass of the Sun, traveled more than 13 billion years until photons fell onto Webb's gold-coated mirror.

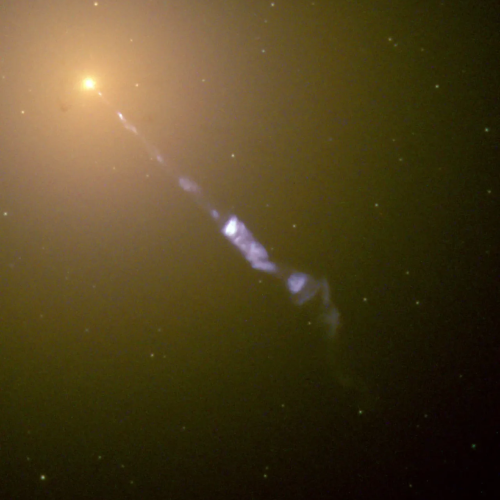

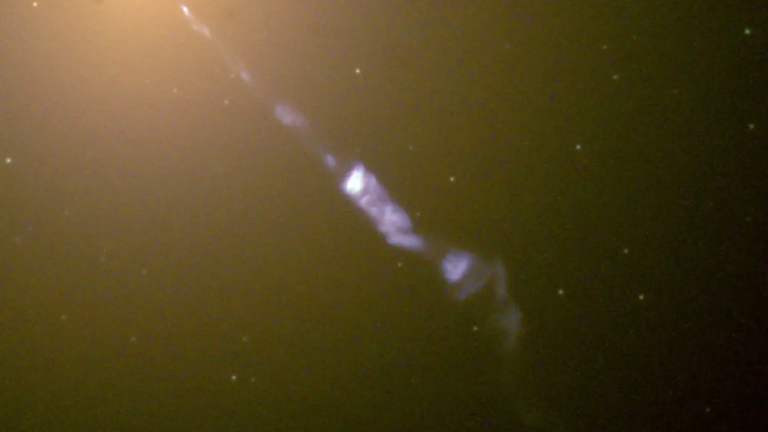

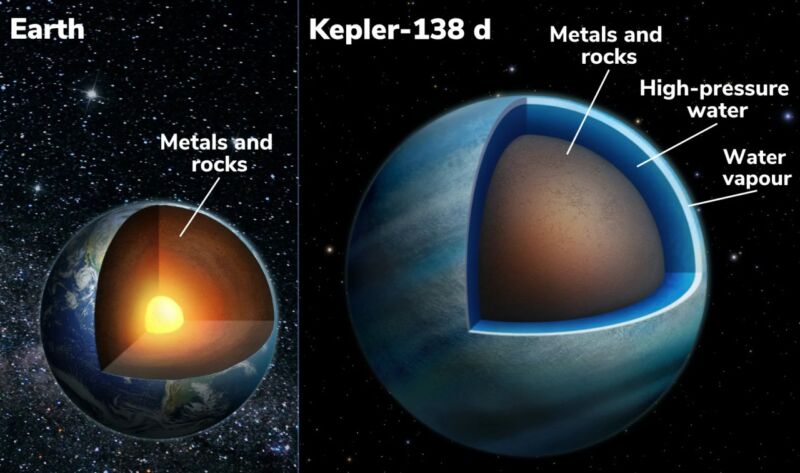

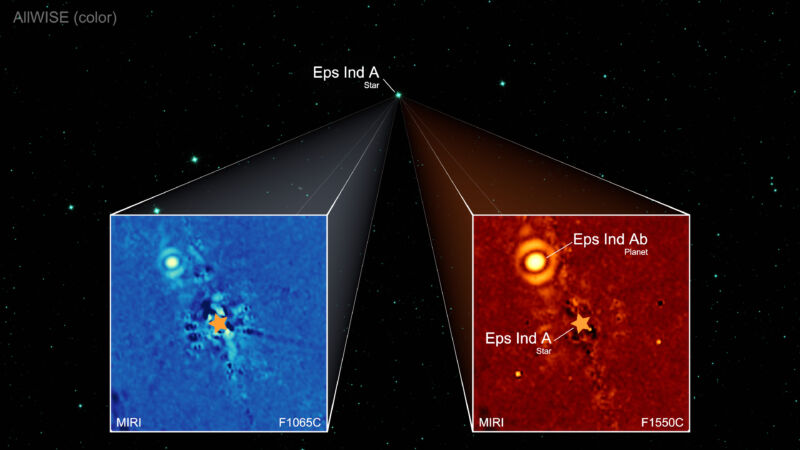

A few months later, in July, scientists released an image Webb captured of a planet circling a star slightly cooler than the Sun nearly 12 light-years from Earth. The alien world is several times the mass of Jupiter and the closest exoplanet to ever be directly imaged. One of Webb's science instruments has a coronagraph to blot out bright starlight, allowing the telescope to resolve the faint signature of a nearby planet and use spectroscopy to measure its chemical composition.

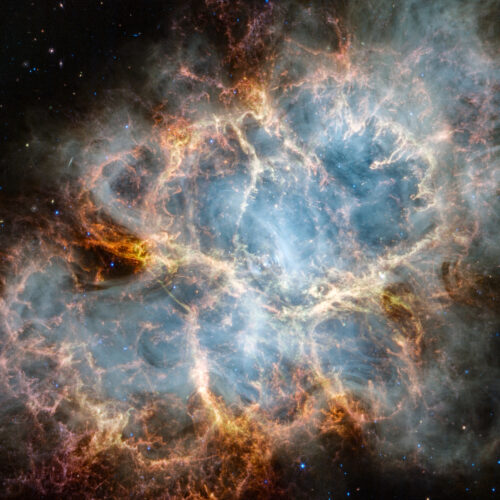

© NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, T. Temim (Princeton University)