A $60 Billion-a-Year Climate Solution Is Sitting in Our Junk Drawers

I meet Baba Anwar in a crowded, chaotic market in the city of Lagos, Nigeria. He claims he’s in his early 20s, but he looks 15 or 16. Maybe all of 5 feet tall, he’s wearing plastic flip-flops, shorts, and a filthy “Surf Los Angeles” T-shirt and clutching a printed circuit board from a laptop computer, which he says he found in a trash bin. That’s Anwar’s job, scrounging for discarded electronics in Ikeja Computer Village, one of the world’s biggest and most hectic marketplaces for used, repaired, and refurbished electronic products.

The market fills blocks and blocks of narrow streets, all swarming with people jostling for access to hundreds of tiny stalls and storefronts offering to sell, repair, or accessorize digital machinery—laptops, printers, cellphones, hard drives, wireless routers, and every variety of adapter and cable needed to run them. The cacophony of a thousand open-air negotiations is underlaid with the rumbling of diesel generators, the smell of their exhaust mixing with the aroma of fried foods hawked by sidewalk vendors. Determined motorcyclists and women in brightly colored dresses carrying trays of little buns on their heads thread their way through the crowds.

It’s no place for an in-depth conversation, but with the help of my translator, local journalist Bukola Adebayo, I gather that Anwar arrived here about a year before from his deeply impoverished home state of Kano. “No money at home,” he explains. In Lagos, a pandemoniac megalopolis of more than 15 million, he shares a room with a couple of friends from home, also e-waste scrappers. On a good day, he says, he can make as much as 10,000 naira—about $22 at the time of my visit.

Thousands of Nigerians make a meager living recycling e-waste, a broad category that can consist of just about any discarded item with a plug or a battery. This includes the computers, phones, game controllers, and other digital devices that we use and ditch in ever-growing volumes. The world generates more than 68 million tons of e-waste every year, according to the UN, enough to fill a convoy of trucks stretching right around the equator. By 2030, the total is projected to reach 75 million tons.

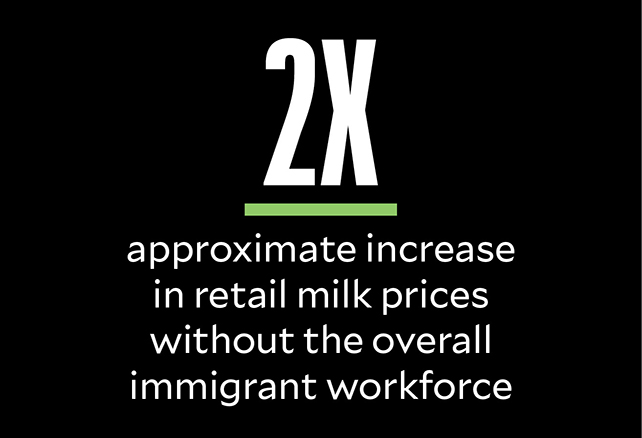

Only 22 percent of that e-waste is collected and recycled, the UN estimates. The rest is dumped, burned, or forgotten—particularly in rich countries, where most people have no convenient way to get rid of their old Samsung Galaxy phones, Xbox controllers, and myriad other gadgets. Indeed, every year, humanity is wasting more than $60 billion worth of so-called critical metals—the ones we need not only for electronics, but also for the hardware of renewable energy, from electric vehicle (EV) batteries to wind turbines.

Millions of Americans, like me, spend their workdays on pursuits that lack any physical manifestation beyond the occasional hard-copy book or memo or report. It’s easy to forget that all these livelihoods rely on machines. And that those machines rely on metals torn from the Earth.

Consider your smartphone. Depending on the model, it can contain up to two-thirds of the elements in the periodic table, including dozens of metals. Some are familiar, like the gold and tin in its circuitry and the nickel in its microphone. Others less so: Tiny flecks of indium make the screen sensitive to the touch of a finger. Europium enhances the colors. Neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium are used to build the tiny mechanism that makes your phone vibrate.

Your phone’s battery contains cobalt, lithium, and nickel. Ditto the ones that power your rechargeable drill, Roomba, and electric toothbrush—not to mention our latest modes of transportation, ranging from plug-in scooters and e-bikes to EVs. A Tesla Model S has as much lithium as up to 10,000 smartphones.

The millions of electric cars and trucks hitting the planet’s roads every year don’t spew pollutants directly, but they’ve got a monstrous appetite for electricity, nearly two-thirds of which still comes from burning fossil fuels—about one-third from coal. Harvesting more of our energy from sunlight and wind, as crucial as that is, entails its own Faustian bargain. Capturing, transmitting, storing, and using that cleaner power requires vast numbers of new machines: wind turbines, solar panels, switching stations, power lines, and batteries large and small.

You see where this is going. Our clean energy future, this global drive to save humanity from the ever-worsening ravages of global warming, depends on critical metals. And we’ll be needing more.

A lot more.

In all of human history, we have extracted some 700 million tons of copper from the Earth. To meet our clean energy goals, we’ll have to mine as much again in 20-odd years. By 2050, the International Energy Agency estimates, global demand for cobalt for EVs alone will soar to five times what it was in 2022. Demand for nickel will be 10 times higher. Lithium, 15 times. “The prospect of a rapid increase in demand for critical minerals—well above anything seen previously in most cases—raises huge questions about the availability and reliability of supply,” the agency warns.

Metals are natural products, but the Earth does not relinquish them willingly. Mining conglomerates rip up forests and grasslands and deserts, blasting apart the underlying rock and soil and hauling out the remains. The ore is processed, smelted, and refined using gargantuan, energy-guzzling, pollution-spewing machines and oceans of chemicals. “Mining done wrong can leave centuries of harm,” says Aimee Boulanger, head of the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance, which works with companies to develop more sustainable extraction practices.

“The long lead times for new mining projects pose a serious challenge to scaling up production fast enough to meet growing mineral demand for clean energy technologies.”

The harm is staggering. Metal mining is America’s leading toxic polluter. It has sullied the watersheds of almost half of the rivers in the American West. Chemical leaks and mining runoff foul air and water. The mines also generate mountains of hazardous waste, stored behind dams that have a terrifying tendency to fail. Torrents of poisonous sludge pouring through collapsed tailings dams have contaminated waterways in Brazil, Canada, and elsewhere and killed hundreds of people—in addition to the hundreds, possibly thousands, of miners who die in workplace accidents each year.

To get what they’re after, mining companies devour natural resources on an epic scale. They dig up some 250 tons of ore and waste rock to get just 1 ton of nickel. For copper, the ratio is double that. Just to obtain the metals inside your 4.5-ounce iPhone, 75 pounds of ore had to be pulled up, crushed, and smelted, releasing up to 100 pounds of carbon dioxide. Mining firms also suck up massive quantities of water and deploy fleets of drill rigs, trucks, diggers, and other heavy machinery that collectively belch out up to 7 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

These operations are not popular with the neighbors. Irate locals and Indigenous communities at this moment are fighting proposed critical-metal mines across the United States, in addition to Brazil, Canada, the Philippines, Serbia, and many other countries. At least 320 anti-mining activists have been killed worldwide since 2012—and they are just the ones we know about.

All this said, while researching my book Power Metal, I was surprised to learn that the mining industry no longer gets away—not easily, anyway—with much of the nasty behavior it has been known for. Some collateral damage is inevitable, but a growing awareness of the industry’s history of human rights abuses and dirty environmental practices—as well as public pressure on consumer-facing companies like Apple and Tesla to clean up their supply chains—has made for some real improvements in how big mining firms operate.

Yet even these beneficial developments come with an asterisk: In the 1950s, it took three or four years to bring a new copper mine online in the United States. Now the average windup is 16 years. “The long lead times for new mining projects pose a serious challenge to scaling up production fast enough to meet growing mineral demand for clean energy technologies,” the International Energy Agency warned in 2022.

If this demand can’t be met, the agency added, nations will fail “to achieve the goals in the Paris Agreement,” the 2016 UN treaty aimed at limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (and from which President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to withdraw—again—during his second term).

And then we’re really in trouble.

It’s a vexing conundrum. In my reporting, I have talked to a wide range of people who are deeply and justifiably concerned about the threats our new mining frenzy will pose to the environment. While acknowledging their fears, I would always ask, “Yes, but what’s the alternative?”

Their answer, almost always, was, “Recycling!”

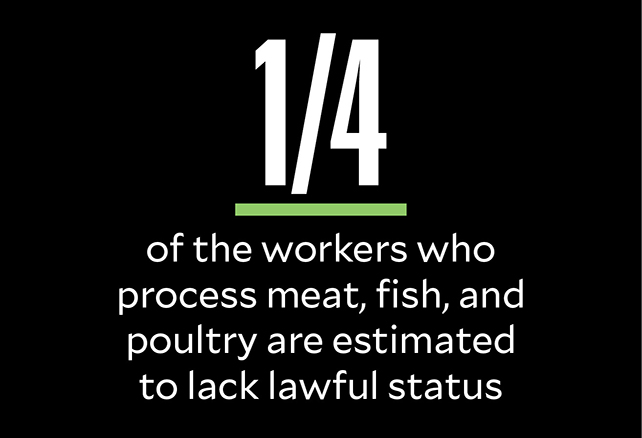

That may sound straightforward. It isn’t. Metal recycling is a completely different proposition from recycling the paper and glass we toss into our home bins for pickup. It turns out that retrieving valuable raw materials sustainably from electronic products—toasters, iPhones, power cables—is a fiendishly complex endeavor, requiring many steps carried out in many places. Manufacturing those products required a multistep international supply chain. Recycling them requires a reverse supply chain almost as complicated.

Part of the problem is that our devices typically contain only a small amount of any given metal. In developing countries, though, there are lots of people willing to put in the time and effort required to recover that little bit of value—an estimated tens of thousands of e-waste scavengers in Nigeria alone. Some go door to door with pushcarts, offering to take or even buy unwanted electronics. Others, like Anwar, work the secondhand markets, buying bits of broken gear from small businesses or rescuing them from the trash. Many scavengers earn less than the international poverty wage of about $2.15 per day.

I ask Anwar where he’s planning to take his circuit board. “To TJ,” he replies, as if I’d asked him what color the sky is.

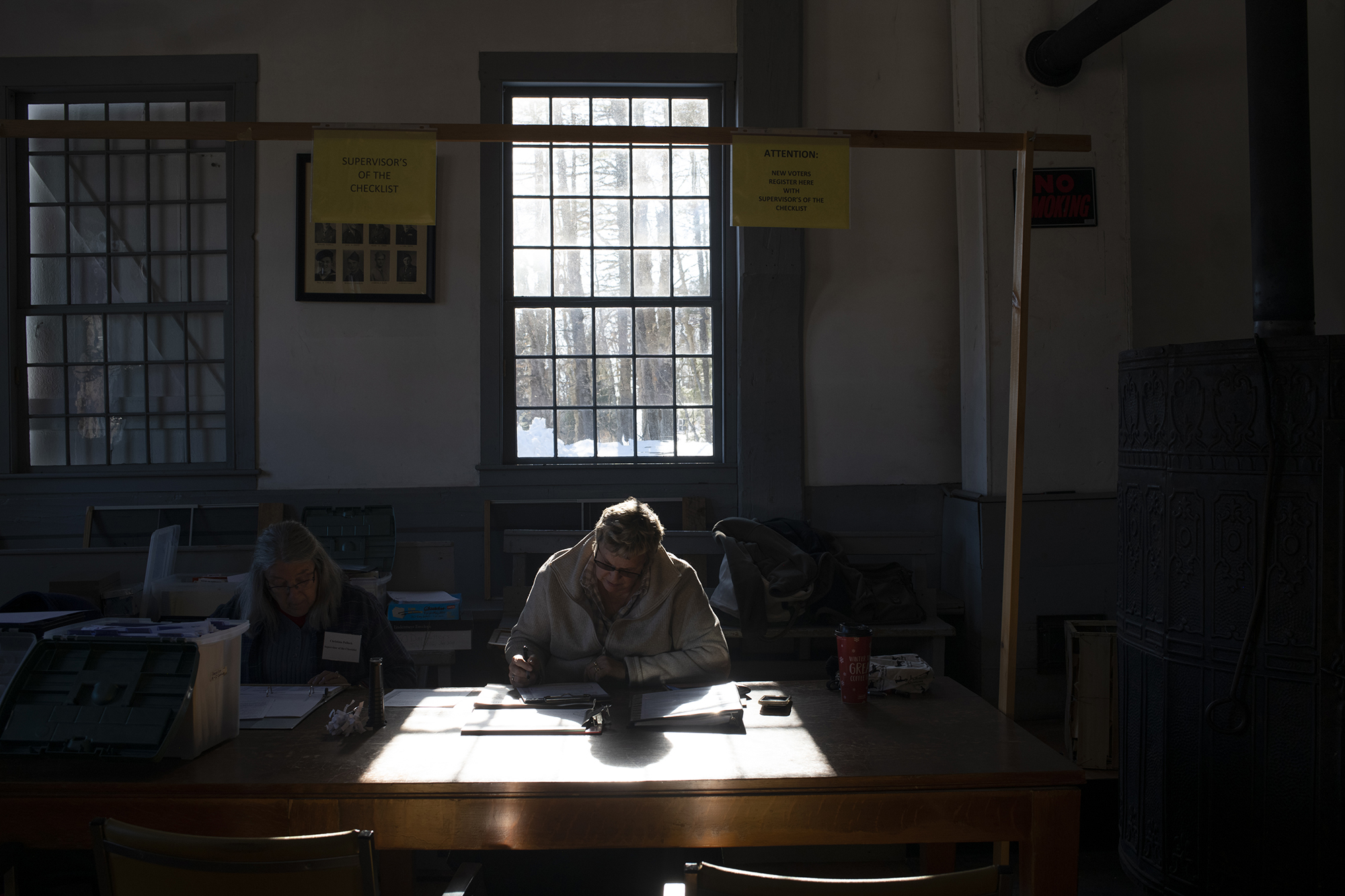

TJ is Tijjani Abubakar, an entrepreneur who has built a thriving business turning unwanted electronics into cash. His third-floor office, in a dingy concrete building across a roaring four-lane road from the Ikeja market, is a charnel house of dead mobile phones. At one end of the long, crowded room, two skinny young men with screwdrivers pull phone after phone from a sack and crack them like walnuts. Their practiced fingers pull out the green printed circuit boards and toss them with a clatter onto a growing heap at their feet.

Thousands of such boards gleam flatly under the glaring LED ceiling lights. More young men sit around on plastic stools sorting them into piles and pulling aside those with the most valuable chips. The air is thick with sweat despite the open windows.

At a scuffed wooden desk sits Abubakar himself—a big man with a steady demeanor, lordly in an embroidered brown caftan, red cap, and crisp beard. I await an audience as he fields calls and messages on three different phones and a laptop while negotiating a deal with a couple of visiting traders over an unlabeled bottle of something.

Abubakar, who looks to be in his mid-40s, has been in the trade nearly 20 years. He, too, hails from Kano, where his father sold clothes—“not a rich man,” he tells me in his even baritone. He earned a business degree from a local university and made his way to Lagos, where a friend introduced him to the e-waste business. “We started small, small, small, small,” he says. But getting a foothold was easier then. Scrap was cheap, even free, because few people were willing to pay for it. Then, as the trade mushroomed, deep-pocketed foreign buyers—from India, Lebanon, and, above all, China—began flocking to Nigeria in search of deals.

“Now everybody knows the prices,” Abubakar says. But his business has flourished. He exports several shipping containers full of e-waste every month to buyers in China and Europe. He’s grown wealthy enough to donate textbooks, meals, and cows to families back in Kano. Dead cellphones converted into education and food. Trash into possibilities.

In 2022, some 5.3 billion mobile phones were discarded globally. Placed end to end, they’d reach almost to the moon and back.

Abubakar handles all manner of e-waste, but the phones are his specialty. There is just shy of one mobile account for every one of Nigeria’s 220 million people. “What do I see here?” he asks, indicating his roomful of workers. “I don’t know whether any of these people have a computer. But I know all of them have a phone.” And all of those phones will one day wear out, malfunction, or get tossed by someone eager for a newer model. In 2022, an estimated 5.3 billion mobile phones were discarded worldwide. If you put them end to end, they’d reach almost to the moon and back.

Abubakar deploys a vast network of buyers and pickers to source spent phones from Nigeria and neighboring countries, and occasionally as far away as France. They arrive by truck, train, and in sacks carried by people like Anwar. These precisely engineered products were manufactured in sophisticated, high-tech factories under ultra-clean conditions. Here, they are eviscerated by hand on a grimy concrete pad.

Abubakar estimates he has about 5,000 workers bringing in millions of phones each year. When I express polite skepticism, he rises and gestures for me to follow. A door in the back of the office leads into a warren of rooms filled either with enormous sacks stuffed with phones, people cracking and sorting phones, or bales of circuit boards ready for shipping.

The most desirable components are those circuit boards, etched with copper and often precious metals, including gold, that carry signals among the soldered-on chips and capacitors. The chips are removed for assessment. If they still work, they can be sold for use in refurbished phones. Abubakar shows me a lunch bag-sized sack of Android chips with serial numbers so tiny I can barely make them out. “This bag is worth around $35,000,” he says. A sack of phone cameras—consisting of the lens you see from the outside attached to a strip of metal foil on the inside—is also valuable. Abubakar trains security cameras on his workers to discourage pilfering. He fired someone the week before for stealing chips, he tells me.

None of the phones were made in Nigeria, and their remains won’t stay here either. Extracting the metals therein requires sophisticated and expensive equipment that no facility in Africa has, so Abubakar sells to recyclers in China and Western Europe that do.

The problem of rich countries “dumping” e-waste on poorer ones has received plenty of attention over the past couple of decades. But in West Africa and other parts of the developing world, most e-waste is now generated domestically. The gadgets passing through Abubakar’s facility were largely imported as new or refurbished products, sold to Nigerian consumers, and later discarded. Relatively little goes to waste. If you live on $2 a day, after all, making a dime from a discarded electric toothbrush is worth your effort. The result is that about 75 percent of Nigeria’s e-waste is collected for some kind of recycling. In nearby Ghana, estimates run as high as 95 percent.

The landscape is different in the United States, where fewer than 1 in 6 dead mobile phones is recycled. The same stat holds in Europe, where roughly two-thirds of all e-waste never makes it into official recycling streams. This is “surprising,” says Alexander Batteiger, an e-waste expert with the German development organization GIZ, “because we have fully functioning recycling systems.”

Or maybe not so surprising. Nobody in the rich world, after all, goes house to house asking for old iPhone 6s or Bluetooth speakers. Sure, there are e-waste collection drives at schools and churches, and you can take old electronics to Best Buy or the local hazardous waste facility—but few people bother. Instead, countless millions of phones and laptops and blenders and microwaves accumulate in attics, closets, junk drawers, garages, and, all too often, the dump.

In Africa, businesses like Abubakar’s keep countless tons of toxic trash out of landfills, reduce the need for mining, and create thousands of jobs—hardly a trivial consideration in a nation where nearly two-thirds of people live in poverty. There’s much to celebrate here. But neither is it the whole story.

An hour’s drive from Abubakar’s office, through a maelstrom of Lagos traffic, sits the Katangua dumpsite, a sprawling, teeming maze of tiny workshops, scrapyards, wrecking zones, and slums, loosely built around a mountain of trash at least 20 feet tall.

This colossus is surrounded by a corroded tin fence held up with bits of scrap wood. Plumes of thick black smoke wend upward from within. The squalor here is unfathomable. The ground underfoot consists of churned-up mud and trampled-in plastic trash. Barefoot children wander among shacks of cardboard, plywood, and plastic sheeting. Adebayo, the local journalist helping me out, and I pick our way around huge puddles, following men and women carrying sacks of discarded metals, all of us retreating to the roadside as trucks piled high with aluminum cans and other scrap wallow past.

Practically every type of metal and e-waste is recycled somewhere in this labyrinth. The resourcefulness of the people is as astonishing as the conditions are appalling. At one yard, owner Mohammed Yusuf proudly shows me his aluminum recycling operation. Pickers bring him cans from all over the city, 2 or 3 tons a day. At the rear of the yard, there’s a covered area with a brick-lined, rectangular hole in the ground about the size of a bathtub, and a smell reminiscent of rotting chicken.

At night, Yusuf tells me, his workers fill the hole with cans, melt them down with a gas-powered torch, then scoop the molten metal into molds using a long ladle. This results in silvery, 2-kilogram ingots pure enough to sell to a manufacturer that makes new cans. The process generates intensely toxic fumes and dust, and his workers wear protective masks. “What about the others nearby?” I ask him. Yusuf nods sagely. That’s why they do it at night, he explains, when the people who live near the yard are asleep in their shacks.

Later, squeezing through a gap in the ragged fence, Adebayo and I find ourselves in an open area at the base of the towering garbage pile. There, four young men are tending small fires, burning the coatings off piles of wire to get at the copper inside. The flames are beautiful—deep cupric blues and greens licking up amid the orange. The smoke, thick and oily and reeking of incinerated plastic and rubber, almost certainly carries dioxins, which are known to cause cancer and harm the reproductive system. The men are wearing shorts, T-shirts, and flip-flops—no respirators or other safety gear in sight.

The smoke, thick and oily and reeking of incinerated plastic and rubber, almost certainly carries dioxins, which are known to cause cancer and harm the reproductive system.

Between the open-air smelting, wire burning, and other miscellaneous wrecking, I’m horrified by the thought of how thoroughly poisoned Katangua must be. “Do you worry about breathing the smoke?” I ask one of the burners, a muscular 36-year-old named Alabi Mohammed. He shrugs: “We don’t know any other job. We don’t have any other option.” He’s been living here since he was 8, he says.

There are other harmful recycling practices I don’t see at Katangua. Scrapped circuit boards are a good source of palladium, gold, and silver—according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, a ton of circuit boards contains from 40 to 800 times the amount of gold found in a ton of ore. You can run them through a shredder and ship the fragments to special refineries, typically in Europe or Japan, where the gold is extracted with chemicals. “It’s a precise, mostly clean method of recycling, but it’s also very, very expensive,” author Adam Minter explains in his 2014 book, Junkyard Planet. In many developing countries, he notes, the gold is “removed using highly corrosive acids, often without the benefit of safety equipment for the workers. Once the acids are used up, they’re often dumped in rivers and other open bodies of water.”

The latter poses clear health and environmental hazards, but it’s cheap and easy, just as extracting copper from plastic-coated wires requires no special equipment—only gasoline and matches. Which is why low-wage laborers around the globe risk their lives burning old extension cords or dousing circuit boards with chemicals to retrieve metals that other low-wage workers risked their lives to dig up in the first place. In Guiyu, home to China’s biggest e-waste recycling complex, studies have found extremely high levels of lead and other toxins in the blood of local children. A 2019 study by Toxics Link, an Indian nonprofit, identified more than a dozen unlicensed e-waste recycling “hotspots” around Delhi employing some 50,000 people—unprotected workers exposed to chemical vapors, metallic dusts, and acidic effluents—and where hazardous wastes were improperly dumped.

Spent lithium batteries present their own recycling challenge. They are potentially among the world’s best sources for critical metals—one study found that battery recycling theoretically could satisfy nearly half of global demand for certain metals. Yet only about 5 percent of them get recycled because they are uniquely hard to handle—and dangerous.

Nigeria, for example, is awash in lithium-ion batteries, but no place on the continent recycles them. They need to be exported. Shippers don’t want to take them, however, because of their disturbing tendency to burst into flames when punctured, crushed, or overheated. Battery fires can exceed 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. They also emit toxic gases and are very hard to extinguish. American consumers are asked to bring unwanted lithium batteries to a domestic recycler or a hazardous waste site, and for good reason. Every year, batteries from everything from old Priuses to sex toys cause hundreds of fires in US scrapyards, landfills, and even on garbage trucks, causing millions of dollars in damage. Residents of Fredericktown, Missouri, even had to evacuate their homes earlier this month when a local battery recycling facility exploded dramatically into flames.

Even in developing countries, unwanted batteries often end up in local landfills, where, beyond the fire risk, they leak toxic chemicals. Or unscrupulous exporters mislabel them, bribing port officials to not examine their shipments too closely. “I’ve heard there’s a major fire every six months,” says Eric Frederickson, vice president of operations at Call2Recycle, America’s largest battery-collection organization, “but you never hear about most of them, because they just tip the container over the side of the boat.”

Reinhardt Smit is trying something different. He’s the supply chain director for Closing the Loop, a Netherlands-based startup that aims to recycle phones from Africa using certifiably sound environmental and social methods: no burned cables, battery fires, trashed plastics, or unprotected workers—every step of the process done responsibly, the way Western consumers like it.

In a 2021 pilot project, Closing the Loop collected and sent 5 tons of phones—plastic, batteries, cables, and all—from Nigeria to a Belgian recycler in what it claims was the first such legally sanctioned shipment ever. The project succeeded from a sustainability standpoint, but it was a money-loser. Clean recycling, it turns out, is hideously expensive.

The phones were sourced from Hinckley Recycling, one of Nigeria’s two (yes, only two) fully licensed e-waste handlers. At Hinckley’s compound on the outskirts of Lagos, workers dismantle phones, computers, and TVs in a clean and well-lit warehouse, wearing reflective vests and protective gloves. It’s clearly a safer and more humane workplace than the others I witnessed, but that adds to the cost.

Convincing a shipper to transport the batteries also required a pricey workaround: They were removed from the phones and placed in barrels filled with sand, eliminating the fire danger. But that meant Closing the Loop had to pay extra to transport hundreds of pounds of sand per shipment.

“It is clear that the biggest mine of the future has to be the car that we already built,” Mercedes-Benz Group Chairman Ola Källenius noted in 2021.

Dealing with unwanted materials was another cost. “If I recycle every component in a phone, I lose money,” explains Adrian Clewes, Hinckley’s managing director. Everyone wants copper, for instance, but phones are mostly plastic, which Closing the Loop must pay a recycler to take. Clewes talks about “positive” and “negative” fractions, meaning the profitable components vs. those that cost him money.

Some fractions toggle between positive and negative depending on the prevailing prices. Say you want to sell a bag of circuit boards containing a total of 1 pound of copper. And say it will cost the smelter $2 to extract the metal. If copper is selling for $4 a pound, the smelter can buy the boards for $1 and make a tidy profit. If copper drops to $3, the deal’s off and the boards are sitting in your warehouse. If you have ample space, you can wait for prices to bounce back. If not, maybe you’re tempted to bring those boards to the dump.

Finally, you have your administrative costs. Global regulations preventing rich countries from dumping hazardous waste on poorer ones have, ironically enough, made it harder to get waste out of the poor countries. The Basel Convention, for one, requires any ship carrying e-waste to get approval from the exporting and importing countries and consent from any country where it might dock en route. This creates oceans of red tape. “Observing the Basel notifications can be painful. It takes months,” says Batteiger, the German e-waste expert. “The Basel Convention is valuable—without it, there would be more dumping—but it has the side effect of blocking exports from the developing world to industrialized countries.”

All told, the cost of doing things by the book makes it almost impossible to turn a profit. Smit’s idea is to get green-minded corporations to cover the difference by paying him to recycle one dead African phone for each new phone it buys.

The concept is akin to selling carbon offsets, and it’s gaining some traction. Closing the Loop now operates in some 10 African countries and has collected several million dead electronic devices. Its near-future target is 2 million phones per year, though that’s admittedly a drop in the bucket. “There are 2 billion phones sold every year,” concedes founder Joost de Kluijver. “We can’t collect all that.”

Comparing the efforts of companies like Closing the Loop and those of the “informal” sector in Nigeria and elsewhere, which provides jobs for thousands of desperate people, it’s hard to say which is better. One might ask, better for whom? Unregulated dumping, wire burning, and the lack of safety equipment don’t meet Western environmental and labor standards. But those standards aren’t top of mind for people who can barely feed and house themselves.

There are other geopolitical aspects to the race for critical metals. Russia, for example, is a prodigious exporter of copper, nickel, palladium, and other metals so crucial that they were spared from international sanctions after Vladimir Putin launched his war on Ukraine. And then there’s China, which—via its own resources, lax standards, diplomatic clout, and overseas investments—has come to dominate the global supply chain.

Regardless of origin, most critical metals will at some point pass through China, which controls more than half of global refining capacity for cobalt, graphite (another battery ingredient), and lithium, and almost as much for nickel and copper. Using those metals, its factories pump out most of the world’s solar panels, a hefty share of its wind turbines, and a majority of its EVs. It also produces nearly three-quarters of lithium-ion batteries and recycles far more of them than any other nation. A subsidiary of CATL, China’s biggest battery maker, can now recycle up to 120,000 tons per year and is investing billions in new plants.

Congress, having deemed China’s dominance in these sectors a threat “to economic growth, competitiveness, and national security,” has responded by sinking money into alternative sources. The 2022 infrastructure bill included $7 billion to develop a domestic supply chain for battery minerals, and the Inflation Reduction Act, passed the same year, unlocked billions more to subsidize batteries and EVs manufactured with domestically sourced metals—though some of the funds may be clawed back or left unspent under the new Republican leadership.

“The economics are very challenging…There’s no clear solution on how to get these things out of people’s drawers.”

In the United States and elsewhere, major automakers are partnering with recyclers and even building their own plants, recognizing that old batteries are a cheaper, cleaner, and more appealing source of critical metals than mining is. “It is clear that the biggest mine of the future has to be the car that we already built,” Mercedes-Benz Group Chairman Ola Källenius said at a 2021 climate summit. In remote Nevada, a company called Redwood Materials has built an enormous EV battery recycling operation. Redwood has inked deals with Tesla, Amazon, and Volkswagen and has attracted nearly $2 billion in capital.

Redwood’s main rival is Canada-based Li-Cycle, which had more than 400 employees at the time of my visit. The company partners with commodities giant Glencore and boasts facilities in Arizona, Alabama, New York; Kingston, Ontario; and elsewhere. Earlier this month, Li-Cycle secured a $475 million line of credit from the Department of Energy. It is now capable of processing about 53,000 tons a year of shredded battery material, which consists mainly of copper and aluminum flakes, plus a grainy sludge known as “black mass” that contains cobalt, lithium, and nickel.

At the company’s Kingston headquarters, I get a tour from Ajay Kochhar, a chemical engineer with neatly combed black hair who co-founded Li-Cycle in 2016 with a metallurgist pal. “We heard lots of people say, ‘You guys are too early,’” he tells me with a smile. The company produced its first batch of shredded battery material that year. “It took us three months to get 20 tons,” Kochhar says. Five years later, his company went public at a valuation of almost $1.7 billion. (As of this writing, the number is considerably lower.)

On the day of my visit, an aggregator had delivered a truckload of batteries from laptops, cellphones, and power tools. I watch as the batteries are loaded onto a conveyor belt, where workers strip off plastic casings and packaging and check labels to make sure they are indeed lithium-ion batteries. Further along, the batteries are dumped into a column of water leading to a shredder whose mighty steel teeth rip them into tiny pieces. Any remaining plastic floats to the surface and is skimmed off. The metals are separated in further steps. Breakfast-cereal-sized flakes of copper and aluminum are poured into large, heavy plastic bags, leaving the black mass behind. Li-Cycle currently sells the former metals to companies like Glencore, which make them into ingots. The black mass goes to other firms that use chemicals to extract the remaining metals.

Perhaps the biggest immediate challenge for companies like Li-Cycle, oddly, is a dearth of batteries to shred. It’s mostly pre-consumer factory scrap and defective batteries from manufacturers keeping their conveyers busy. EVs are so new to the market that few have been junked—and even those are often snapped up for uses such as off-grid power storage. Most consumer lithium batteries aren’t collected at all. “We’ve looked at doing the collection ourselves, but the economics are very challenging,” Kochhar told me. “There’s no clear solution on how to get these things out of people’s drawers.”

The sap of Pycnandra acuminata, which grows on the nickel-rich island of New Caledonia, can contain more than 25 percent nickel.

So how can more e-waste be brought into the reverse supply chain? One approach is to shift the onus onto the firms that manufactured the gadgets in the first place, a policy known as “extended producer responsibility.” China and much of Europe have codified this policy in laws that govern not only e-waste, but also glass, plastics, and even cars. Sometimes, it just means charging manufacturers a fee to help cover the downstream recycling costs. In the EU, though, carmakers are responsible for collecting and recycling their own dead vehicles. China, which since 2018 has required manufacturers to collect and recycle lithium-ion batteries, also mandates that new batteries contain minimum amounts of certain recycled materials.

China now recycles at least half of its batteries, according to CATL. “In North America, it’s mainly us and Redwood,” Kochhar says. “There are many more in Europe.” But what’s happening in China, he says, “is way ahead of what we’re doing here.”

As a strictly economic proposition, it’s often cheaper to mine fresh metals than recycle them. And some of the relevant products are tremendously hard to recycle: Less than 5 percent of rare earth magnets are currently recycled, for example, and an estimated 9 in 10 spent solar panels—which cost roughly $20 to $30 to recycle vs. $1 to $2 to bring to the dump—end up in landfills. Ditto the massive blades on wind turbines, of which more than 720,000 tons are projected to be trashed by 2040. The bottom line is that meaningful e-waste recycling in the United States is probably going to require government support.

And why not subsidize? China, our biggest rival in the clean energy sector, offers tax breaks to metal recyclers, even as US taxpayers spend billions subsidizing fossil fuels and mining operations. Under the Biden administration, Congress directed some $370 billion to bolster renewable energy technologies, including nearly $40 billion for nuclear energy and more than $12 billion to promote sales and manufacturing of EVs and their batteries, but has included only a couple of billion toward recycling.

If you’re dissatisfied with your old iPhone 8, there are plenty of people in developing countries who would love to have it.

New technologies might help somewhat. British researchers are working on inexpensive reactors they hope can facilitate recovery of rare earths. In Texas, Apple is testing a robot that can disassemble 200 iPhones per hour to aid in recycling. Mining giant Rio Tinto is experimenting with ways to extract lithium that exists in boron mining waste, and a Canadian startup is working to recover rare earths from tin-mine tailings.

Scientists are even studying plants that can suck up trace metals through their roots and concentrate them in their sap, stems, or leaves. The sap of Pycnandra acuminata, a tree that grows on the nickel-rich Pacific island of New Caledonia, can contain more than 25 percent nickel. Other “hyperaccumulators” slurp up cobalt, lithium, and zinc. Startups are springing up, hoping to capitalize on these special properties, which could also be used to clean up polluted soil.

None of this is a silver bullet. Even if humanity could recover all of the critical metals in use—and we can’t—we’d still have to mine more to meet rising demand. Consider that we now recycle less than 1 percent of the lithium used around the world, and we’ll be mining hard-to-recover rare earths for decades to come. “Nothing—nothing—is 100 percent recyclable, and many things, including things we think are recyclable, like iPhone touch screens, are unrecyclable,” Minter writes in Junkyard Planet. “Everyone from the local junkyard to Apple to the US government would be doing the planet a very big favor if they stopped implying otherwise, and instead conveyed a more realistic picture of what recycling can and can’t do.”

Recycling is important, yes. But it is also utterly insufficient to meet our needs. We tend to think of it as the best alternative to using virgin materials. In fact, it often can be one of the worst. Consider a glass bottle. To recycle it, you have to smash it to pieces, melt down the bits, and mold them into a whole new bottle—an industrial process that requires a lot of energy, time, and expense.

Or you could just wash it and reuse it.

That’s a better alternative—and hardly a new idea. For much of the last century, gas stations, dairies, and other companies sold products in glass bottles that they would later collect, wash, and reuse.

Rendering a phone, car battery, or solar panel down to its constituent metals requires a great deal more energy, cost, and, as we’ve seen, unsafe labor than refurbishing that product. You can buy refurbished computers, phones, and even solar panels online and in some stores. But refurbishing is only really widespread in the developing world. If you’re a North American no longer satisfied with your iPhone 8, there are plenty of people in less-affluent countries who would be happy to take it.

There are important lessons here, and perhaps the most important of all is this: As we look ahead, we will need to start thinking beyond merely replacing fossil fuels with renewables and increasing our supplies of raw materials. Rather, we will need to reshape our relationship to energy and natural resources altogether. That seems like a tall order, but there’s a range of things we can do—as consumers, as voters, as human beings—to assuage the downstream effects of our technological arms race.

Moving forward, our critical metals will come from all sorts of mines and scrapyards and recycling centers around the globe. Some will emerge from new sources, using new methods and technologies. And the choices we make about where and how we get those metals, and who prospers and suffers in the process, are tremendously important. But no less important is the question of how much of all these things we truly need—and how to reduce that need.

We’re lucky in one respect: We’re still only at the beginning of a historic worldwide transition. The key will be figuring out how to make it work without repeating the worst mistakes of the last one.

Follow Vince Beiser’s ongoing reporting at powermetal.substack.com.