‘World of Warcraft’ at 20: Blizzard Team on Milestone Anniversary Plans, Bringing in New Players and the Potential for a Movie Do-Over

SpaceX launched its sixth Starship rocket Tuesday, proving for the first time that the stainless steel ship can maneuver in space and paving the way for an even larger, upgraded vehicle slated to debut on the next test flight.

The only hiccup was an abortive attempt to catch the rocket's Super Heavy booster back at the launch site in South Texas, something SpaceX achieved on the previous flight on October 13. The Starship upper stage flew halfway around the world, reaching an altitude of 118 miles (190 kilometers) before plunging through the atmosphere for a pinpoint slow-speed splashdown in the Indian Ocean.

The sixth flight of the world's largest launcher—standing 398 feet (121.3 meters) tall—began with a lumbering liftoff from SpaceX's Starbase facility near the US-Mexico border at 4 pm CST (22:00 UTC) Tuesday. The rocket headed east over the Gulf of Mexico, propelled by 33 Raptor engines clustered on the bottom of its Super Heavy first stage.

© SpaceX.

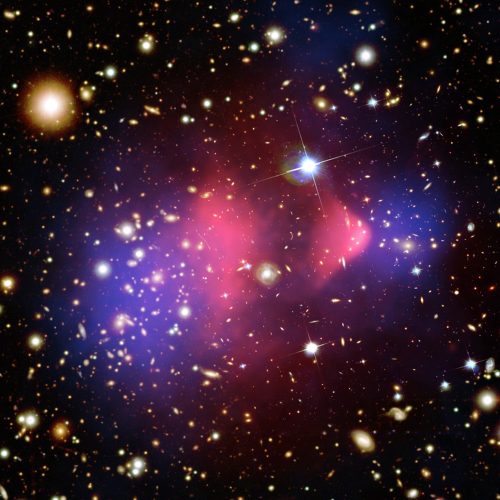

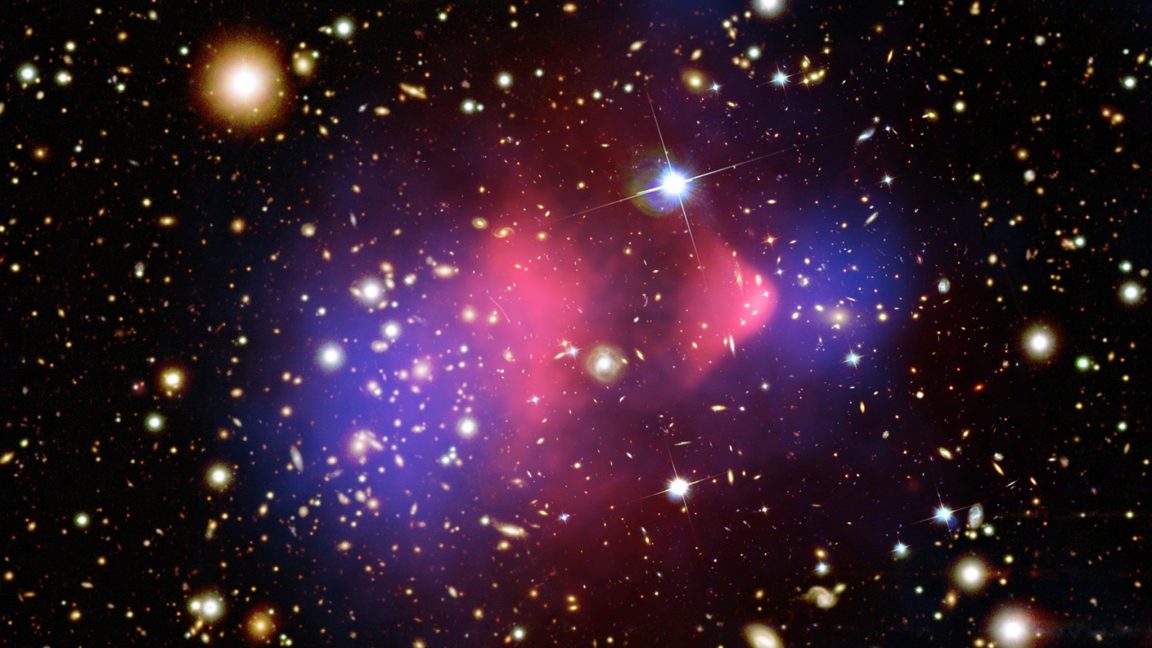

Emergent gravity is a bold idea.

It claims that the force of gravity is a mere illusion, more akin to friction or heat—a property that emerges from some deeper physical interaction. This emergent gravity idea might hold the key to rewriting one of the fundamental forces of nature—and it could explain the mysterious nature of dark matter.

But in the years since its original proposal, it has not held up well to either experiment or further theoretical inquiry. Emergent gravity may not be a right answer. But it is a clever one, and it's still worth considering, as it may hold the seeds of a greater understanding.

© APOD

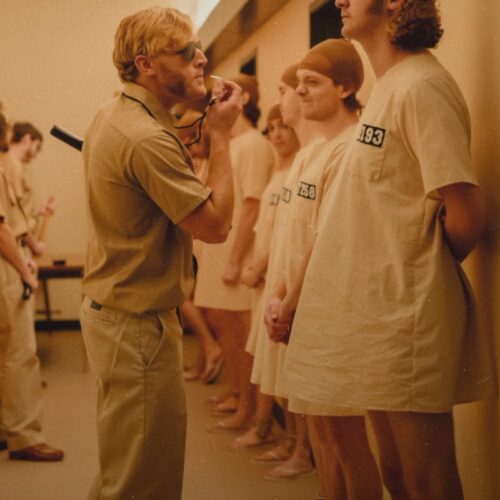

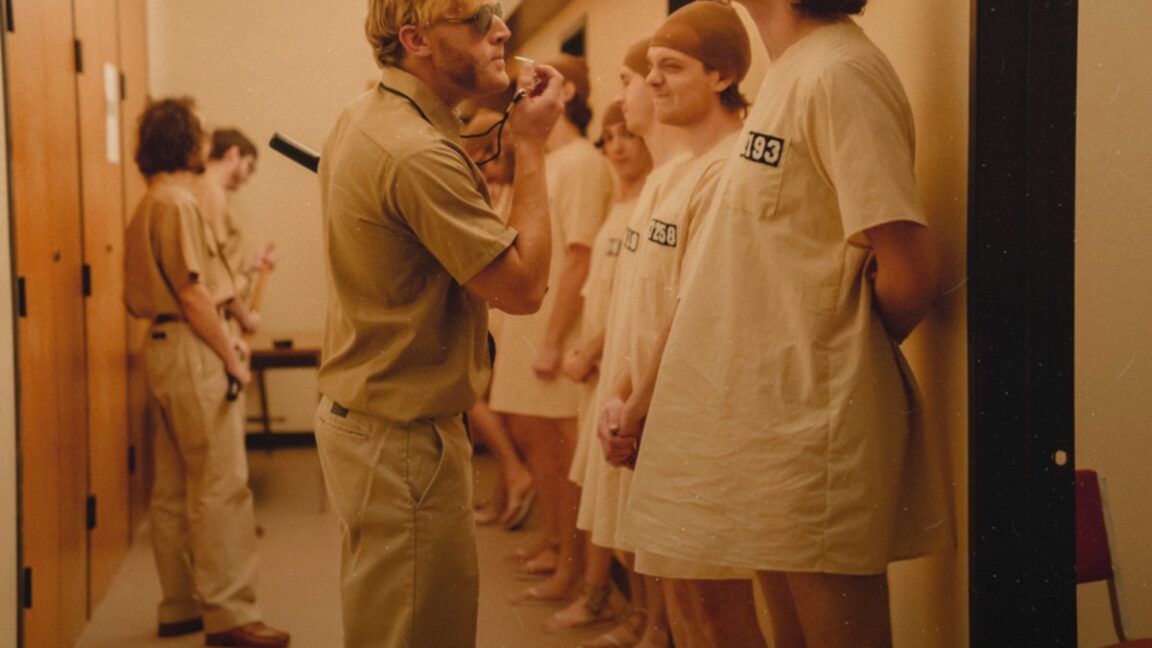

In 1971, Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo conducted a notorious experiment in which he randomly divided college students into two groups, guards and prisoners, and set them loose in a simulated prison environment for six days, documenting the guards' descent into brutality. His findings caused a media sensation and a lot of subsequent criticism about the ethics and methodology employed in the study. Zimbardo died last month at 91, but his controversial legacy continues to resonate some 50 years later with The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth, a new documentary from National Geographic.

Director Juliette Eisner started working on the documentary during the pandemic when, like most people, she had a lot of extra time on her hands. She started looking at old psychological studies exploring human nature and became fascinated by the Stanford Prison Experiment, especially in light of the summer protests in 2020 concerning police brutality. She soon realized that the prevailing narrative was Zimbardo's and that very few of the original subjects in the experiment had ever been interviewed about their experiences.

"I wanted to hear from those people," Eisner told Ars. "They were very hard to find. Most of them were still only known by alias or by prisoner number." Eisner persevered and tracked most of them down. "Every single time they picked up the phone, they were like, 'Oh, I'm so glad you called. Nobody has called me in 50 years. And by the way, everything you think you know about this study is wrong,' or 'The story is not what it seems.'"

© National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

During my first semester as a computer science graduate student at Princeton, I took COS 402: Artificial Intelligence. Toward the end of the semester, there was a lecture about neural networks. This was in the fall of 2008, and I got the distinct impression—both from that lecture and the textbook—that neural networks had become a backwater.

Neural networks had delivered some impressive results in the late 1980s and early 1990s. But then progress stalled. By 2008, many researchers had moved on to mathematically elegant approaches such as support vector machines.

I didn’t know it at the time, but a team at Princeton—in the same computer science building where I was attending lectures—was working on a project that would upend the conventional wisdom and demonstrate the power of neural networks. That team, led by Prof. Fei-Fei Li, wasn’t working on a better version of neural networks. They were hardly thinking about neural networks at all.

© Aurich Lawson | Getty Images