Searching for Democracy and Finding America

Democracy is at once everywhere and nowhere—on the lips of the masses calling for freedom and fearing for its safeguarding, while every day asking the question: What even is democracy?

Starting in 2018, that is the question the Our Democracy team—me along with photographer Andrea Bruce and educator and videographer Lorraine Ustaris—set out to answer. Our starting point wasn’t simple, but it was frank. We would travel cross-country to see how Americans live and hear what they say democracy looks like in their daily lives.

We decided to follow in the footsteps of French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville, who toured the United States in the 1830s and wrote an assessment about why democracy seemed to be succeeding here but had failed in other places. We began with the first words of Tocqueville’s 1835 volume of Democracy in America:

“Of all the novel things which attracted my attention during my stay in the United States, none struck me more forcibly than the equality of social conditions,” he wrote. “I had no difficulty in discovering the extraordinary influence this fundamental fact exerts upon the progress of society.”

For Tocqueville, the “equality of social conditions” is a core principle of democracy that, broadly, meant the absence of aristocracy—a societal state in which, on individual levels, there are few divisions between the people based on birth, wealth, or social status. (Although Tocqueville did note that this equality was one to be found solely among white Christian men. The prejudice against Black Americans was then appearing to “increase in proportion to their emancipation,” he wrote, and he wondered how the United States would recover from being born of the mass genocide of Native Americans.)

“I have looked [in America] for an image of the essence of democracy, its inclinations, its personality, its prejudices, its passions,” Tocqueville concluded. “My wish has been to know it if only to realize at least what we have to fear or hope from it.”

We found a crisis of democracy underlying that of our political fever.

Nearly 200 years later, we set out to examine these social conditions—and to provide an updated record of the state of democracy, local and national, at this moment in American history.

What we found was a crisis of democracy underlying that of our political fever. A historical, generational, and ongoing inequality and a systemic exclusion—both racial and economic. Scholars like Martin Wolf, author of The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, have said this inequality has been abetted by the neoliberal system, which “poses the most immediate threat to civil society.”

Neoliberalism is loosely defined as the economic system in play from the late 1970s to the 2008 financial crisis. Since then, a study by the Pew Research Center found that even as the economy was growing following the end of the Great Recession in 2009, the gap in income between upper-income and middle- and lower-income households was also rising, with upper-income households seeing more economic growth faster. In 2023, the World Inequality Database reported that the United States is the only country in North America and Oceania in which more than 20 percent of national income goes to the wealthiest 1 percent, with nearly 50 percent going to the top 10 percent.

We found that this crisis of inequality has festered into near-total disillusionment and consequent democratic atrophying on community levels, what Tocqueville referred to as a “loss of spirit,” which he warned could lead to tyranny. Yet we also observed an impulse to form hyperlocal microcosms of democracy to help keep the community alive on an individual level—in Tocqueville’s words, “spirit of association” or “self-governing” that generates democratic participation.

Crisis, in this sense, is a paradox, a kind of duality—a sort of pharmakon, as philosopher Jacques Derrida might say—both the sickness that kills democratic participation and perhaps the medicine that restores it.

In Paradise, California, a wildfire decimated the community while activating a group of individuals to restore its livability and ensure its survival.

The November 2018 Camp Fire—the deadliest in the state’s modern history—devastated Paradise, a town in the Sierra Nevada foothills, killing 85 people in Butte County, displacing 50,000, and destroying roughly 14,000 homes. There, we were told persistently and insistently what a great leveler the fire had been. On Valley View Drive, “the richest street in Paradise,” where “you get the full-sized candy bars on Halloween,” $500,000 homes were reduced to fences left standing guard around empty lots. As federal and nonprofit humanitarian aid came and went, residents grew tired of the restrictions and empty promises they said came with it. They started to decline the help and decided instead, despite being unable to lean on neighbors since so many had lost homes and jobs themselves, to use the community to build the safety net all the outside aid could not. It was through the disaster and around its resulting adversity that the community came to congeal.

I couldn’t help thinking back to our time in Detroit in July 2019. There, we had a chance encounter with an elder named Elemiah Sanders. I was standing on the street, looking at a burned-out home, when Sanders called out to me from behind: “Young lady! What are you all out here doing?” I introduced myself and our project. He looked around before offering his thoughts: “The people lost their spirit,” he told me about his neighbors. “They don’t participate. I think it might be one of those things where we need a disaster to come up and raise up the neighborhood, but I hope it’s not that way.”

When independence and authority are no longer accessible to the community, Tocqueville urged, when the liberty to self-govern with representational significance that promotes equality is impeded, the ability and desire to swim against the current, to fight to participate when it is felt that participation has been wrenched from the people, wearies, making certain that the institutions and their communities both falter. Spirit withers. It’s just our human nature. Tocqueville insisted: “Patriotism does not long prevail in a conquered nation.” And I came to realize that was true on hyperlocal levels as well.

In Warner Robins, Georgia, the spirit of patriotism is such a part of life and what residents believe democracy to be that it’s in its official motto: EDIMGIAFAD, or Every Day in Middle Georgia Is Armed Forces Appreciation Day. The city between Houston and Peach counties is home to Robins Air Force Base, and American flags appear on house after house as you drive through its neighborhoods. But at the time of visiting in August 2018, the city also had one of the lowest voter turnout rates in the country.

Larry Curtis, a manager of the drones called “Blue Seaters” on the Air Force base and owner of the Curtis Office Suites, said it all comes down to both “the haves and the have-nots” abstaining from participation, “not calling out local injustice like misallocation of funds,” because the “haves feel comfortable and the have-nots feel like it won’t make a difference.”

The afternoon Curtis drove us onto base, the gray skies expected thunderstorms. It was no matter to Curtis, he kept driving all the same, past two officers holding M16s and pulling a car over, giving us the breakdown of the city’s economically organized geographical divide. He took us out onto Watson Boulevard, which was the zero degree—on one side was the north side, or “the blighted areas,” and on the other was the south side. A church marquee on the north side of Watson read, “When you reach the end of your rope, look up.”

I asked Curtis what was the biggest problem Warner Robins faced. He answered first with just one word, “equality,” and then went on to explain. “Because when you see one part of town and then the other, you see it’s not equal, even down to cutting the grass,” he began. “In the nighttime, you see the lights—there’s no lights on this [north] side of town. The street lamps are out and you can’t get nobody to come out and fix it. The money’s on the south side,” he continued, before adding, “I hate to say the word ‘racial’—I’m more about what’s wrong and what’s right.”

“At the city council meetings, they ask every other week about getting the lights fixed and getting the grass cut,” he said. “So the big problem is really down at city hall.”

We went to one of those city council meetings and watched residents address council members one after the other, to little or no response. It was clear there was a kind of agitated exhaustion among the residents, where they were almost too tired to keep speaking up just to remain unseen and unheard, but all there was to do was keep speaking up, so they did—the few who had the persistence and made the time to deliver it, for the sake of the many who had largely, as Curtis said, given up.

Democracy is not working, he told us, because the people don’t exercise their right to vote. Instead, he added, they just accept things for what they are, making it hard to know how to help create change.

Despite voting being one of the answers we heard most frequently to the question of what democracy is, it was this loss of spirit, which Tocqueville referred to as a side effect of losing the power to self-govern, we witnessed atrophying democratic participation. And that loss of spirit is not always a choice. In vastly different communities occupying vastly different parts of the country, that loss of spirit in relation to voting was the same, albeit for different reasons.

In Memphis in 2018, we spoke with ex-offenders working hard to put their lives back together through the community organization Lifeline to Success, only to continue to confront what was for many of them an unthinkable and unending punishment: felony disenfranchisement. They felt subjected to a system of governing they have no say in, despite having paid their dues to society, and that their lives were being irrevocably shaped by decisions being made for them that they might not have made for themselves.

In San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 2021, locals referred to themselves as a colony, with no say in the colonizer’s impact on their lives. Puerto Ricans, as citizens of a territory of the United States, are not granted the right to vote in presidential elections. Vieques, a small island off Puerto Rico’s eastern coast known outside Puerto Rico as the former US Navy bomb training range and testing site, is known by Viequenses as “the colony of a colony.” The sense of silenced despair was especially pronounced as residents, many of them veterans, struggled with everything from meeting basic needs to transportation and the inexistence of medical care amid astronomically high cancer rates—the result of American military pollution, specifically from plutonium and Agent Orange.

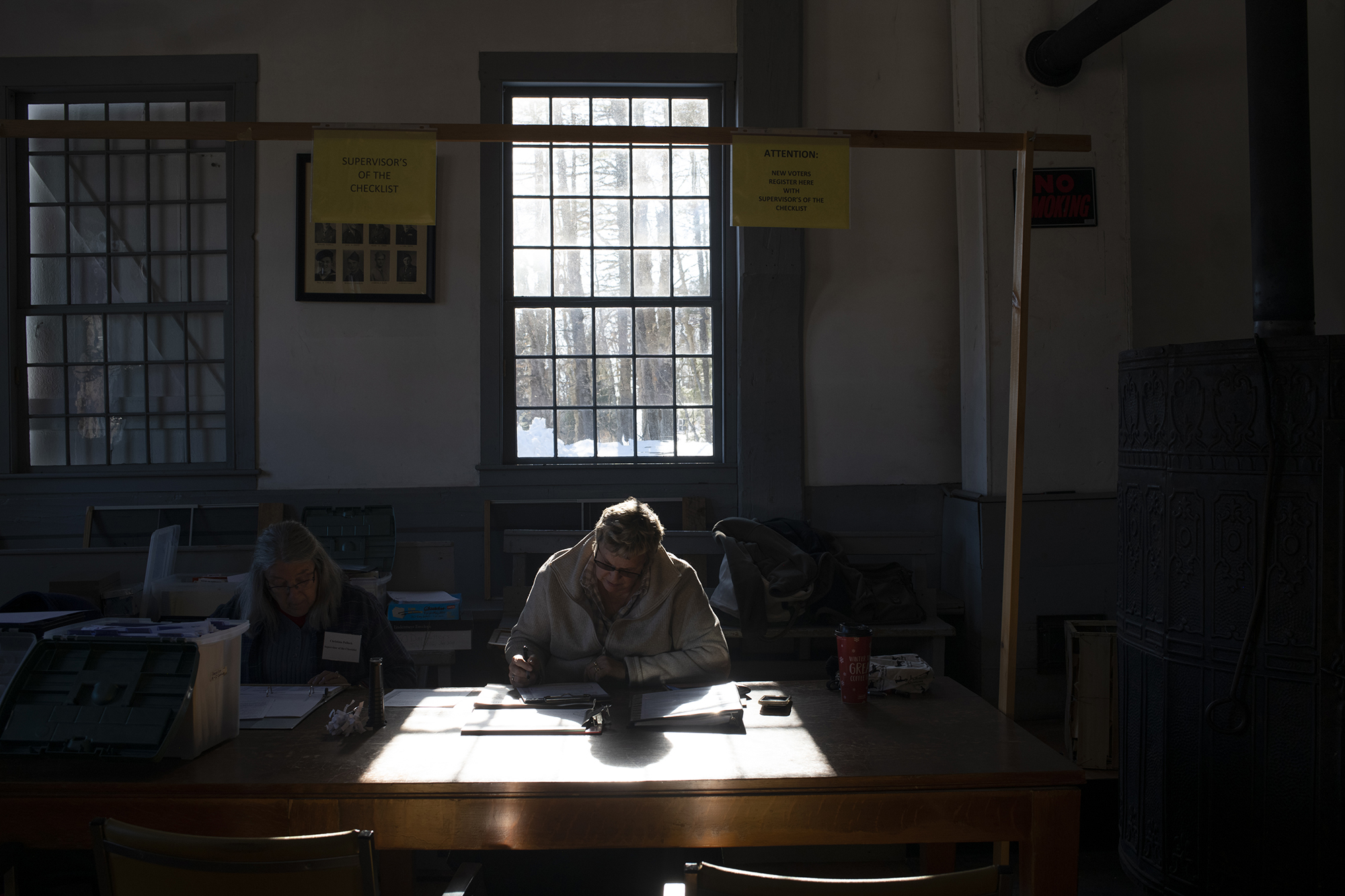

With respect to voting, of the dozen locations we traveled to across the country, one stands out: New Hampshire. We bounced around more than a dozen towns—places like Laconia and Meredith; Tilton, Salisbury, and Moultonborough; Wilmot, Concord, Andover, and Franklin— visiting town hall meetings, schools, families living off the grid, and libertarians, and each town was largely the same. Participation in local direct democracy was not only high, it was an important and ongoing source of pride in the community. Asked why it was such a central part of life in the “live free or die” state, residents said it had always been that way and was a matter of the personal nature of caring for democracy and a sense of duty. But homogeneity also helps. New Hampshire is more than 60 percent white, with an average household income of $90,000 and a 2.6 percent unemployment rate, as of 2024. Self-governing in the best interest of the whole community is often an infinitely smoother negotiation, a process almost unimpeachably straightforward, when most of the members of that community share a relatively secure lived experience.

In most communities we visited, an enduring existential struggle with poverty was at the root of a communal loss of spirit, offset by the will of just a few individuals to fight back.

When the coal industry largely responsible for building up McDowell County—the poorest county in West Virginia and among the poorest in the nation—dried up, it took most of the economy, resources, and population with it. The coal industry and the county seat, the city of Welch, were at their peak in the 1950s, with a sudden surge in population from roughly 700 to 100,000 and a thronging city center, but machines began to take over the work of men. The county became the first in the country to receive modern-era food stamps after a 1960 visit by then-presidential candidate John F. Kennedy—a program residents said decimated the community, because, they said, they needed jobs, not food stamps. More than once, residents referred to their county as “America’s forgotten county,” left to themselves and out of the national conversation when it was no longer carrying the weight of the state’s economy. Today, McDowell County is notorious as the coal country that changed its often-Democratic vote to Republican in the 2016 presidential election.

By 2019, most of Welch’s downtown area was shuttered—what remained were a few small businesses, local government services, and the Welch News, the last remaining news source in McDowell County. Missy Nester, the owner and publisher, told us that she would “print until she ran out of paper.” But the paper was forced to fold in the summer of 2023.

“Our people have nothing,” Nester told the Associated Press in July of that year. “Like, can any of y’all hear us out here screaming?”

Nester and the Welch community had pulled together to save the newspaper in 2018 after learning that the owner had plans to close its doors. The Welch News had an entirely voluntary team of local drivers who drove a six-hour route through the hills to hand-deliver papers to readers’ homes. Often, they took bread and milk deliveries with them for the elderly who seldom saw anyone but them, and they checked in on every resident they handed off to. It was an intensely personal system that inspired awe unlike much else does.

“We have been the forgotten place for so long that we’re just used to taking care of each other,” Nester said. “We vote to take care of ourselves.”

In some places, like among a sizable Somali immigrant community in Garden City, Kansas, in 2021, people struggled to build a community infrastructure from scratch where there had never been one at all. What little support they’d once had was provided by the nonprofit outreach organization LiveWell, which offered assistance programs and services to the growing population, but funding dried up and the community was left on its own to face everything from obstacles to medical care, to a bomb threat and the racism that came with it, and landlords that financially exploited refugees. The challenge became how to organize a community that was outward facing, that could integrate itself into American society while holding on to its cultural customs when the people could only turn inward for help, creating—naturally—something far more insular.

I thought a lot then about the importance Tocqueville placed on the idea of “assimilation” as a means of survival, of a group’s adaptability to the social mores of the new Americans as the evidence of whether or not it would ultimately endure American democracy. I thought about, on the one hand, how well the people of New Hampshire felt democracy was working for them and the role of cultural, racial, and economic homogeneity in that, and, on the other hand, I thought about the damage the demand for adaptability, the forced assimilation, has done to entire populations of people who don’t fit into that homogeneity.

Could democracy ever withstand the pressures of governing over the pluralist society we not only have become, but have really always been? It’s a conversation I had with Latrice Tatsey, a citizen of the Blackfeet Nation in Browning, Montana, while watching her children ride at a rodeo in July 2019. In fact, it was a conversation I seemed to be having with many Blackfeet leaders.

The history of the attempted forced assimilation of the Native Americans at the hands of American settlers is, by now, no secret. Today, it is largely recognized as a genocidal effort that decimated the populations of the country’s nations and tribes not just by the violence of slaughter, but by the violence of cultural destruction and dispossession as well. The result is conditions of living—and sometimes dying, as young people face the challenges of poverty, drug addiction, and suicide—caught between “Western influence” and Native tradition, in which leaders have had to work on ways to “keep the cultures indigenous to their peoples alive,” John Murray, the Blackfeet’s tribal historic preservation officer, told me.

“Is it democracy that ruined it all?” he asked. “Corporate democracy?”

It was a question that had come up more than once for us on the road, as people wondered where the line money draws across for whom democracy works and for whom it does not stops. Could even a perfect democracy subsist within the context of America’s particular brand of capitalism? Does the subsistence of one subset of people require the continued subjugation of another—or all others?

“We’ve had a very difficult struggle, always at the mercy of the government for survival,” Virgil “Puggy” Edwards, a member of the Blackfeet Constitutional Reform Committee, said as he gave a rundown of the Blackfeet history he was working on that day at the office, where he takes care of archiving and documentation.

Paradoxically, this work the community does to keep culture, family, and tradition alive for the Blackfeet is largely democratic, Tatsey said. It comes down to a duality of spirit, of patriotism, and for the Blackfeet, democratic participation goes back long before the arrival of the first pilgrims to American shores.

“Our family has adapted to live in both worlds, even though we’re all in this one with our cultural values system, and living in the Western values system—no matter what trauma our people have gone through, they’ve been able to adapt, and that’s why we’re still here today,” she said. “Democracy is, for me, just how our people function for immemorial time, because what you have in our tribal makeup is leaders who, in order to have that leadership role, they had to prove themselves to the people and earn feathers,” she continued. “And so for us, it was what you did for your people and how you were going to guide your people that made the people stand behind you.”

Amid a presidential election—that naturally occurring crisis of democracy, as Tocqueville called it—burning like a wildfire across the country, the slow burn of our secondary crisis, that of the inequality of social conditions, is smoldering. The people, having become incendiary themselves, are a lit powder keg—the spark barreling through the wick. We return to Tocqueville’s words:

“Of all powers, that of public opinion is the hardest to exploit. It is often just as dangerous [for representatives] to lag behind as it is to outpace it.”

The real test of our democracy, for either side of the party line, will be how we get through it—to the other side of not just the wildfire, but of the slow burn. How we make ourselves hard to exploit and make it hard to exploit each other.

Tocqueville believed that our loss of spirit would either paralyze our participation, further heighten our passions, and risk a break of the state, or be the catalyst for us to rise up and save what we each believe to be at stake. If we are able to marvel at these communities’ capacity for togetherness in crisis as a feel-good feat of democracy in spite of “democracy” itself, then we should be, to the same extent, able to learn from it that the power of democracy, to self-govern, must sometimes be the power to use democracy to wrench self-governing back. The power to use democracy against itself, for its own good.

We will perhaps find that the only way to fight for American democracy is for the true equalizer to be us (if we want it). If we must fall to Tocqueville’s “tyranny of the majority,” let it be because our heightened passions have unified not against each other, but to number the people together greater than the flawed system of governance so that the tyranny belongs to us all.

And if it gets too heavy and “you reach the end of your rope,” like that church marquee on the north side of Watson Boulevard in Warner Robins preached, just “look up.” The real work of regeneration comes after the fire.