We’re closer to re-creating the sounds of Parasaurolophus

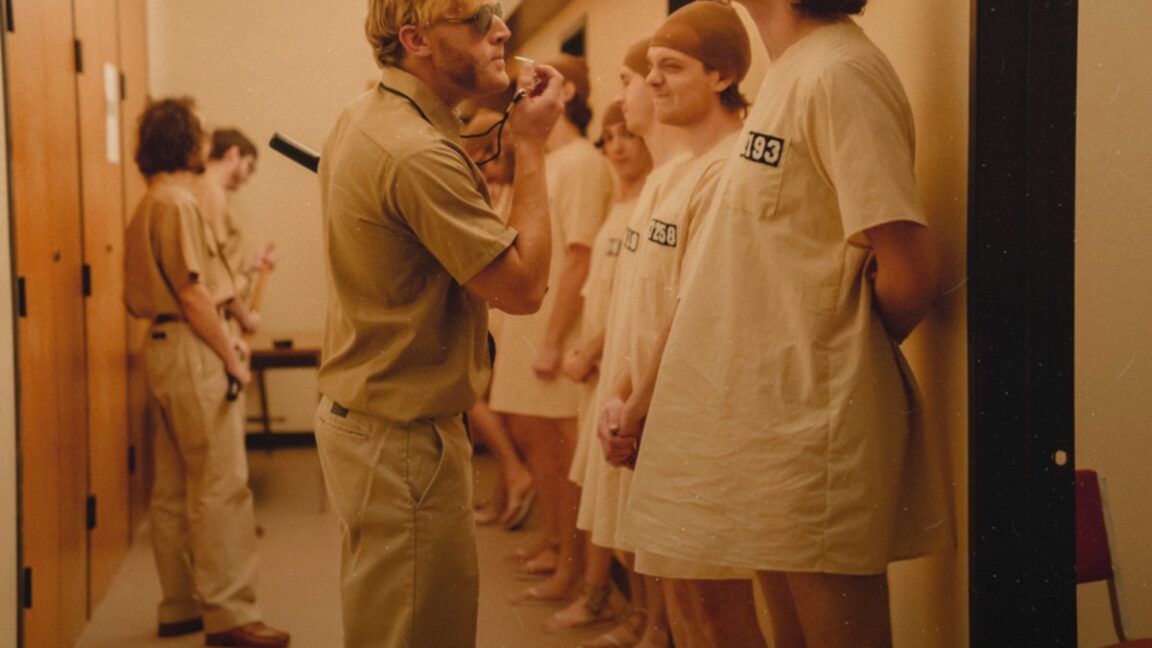

The duck-billed dinosaur Parasaurolophus is distinctive for its prominent crest, which some scientists have suggested served as a kind of resonating chamber to produce low-frequency sounds. Nobody really knows what Parasaurolophus sounded like, however. Hongjun Lin of New York University is trying to change that by constructing his own model of the dinosaur's crest and its acoustical characteristics. Lin has not yet reproduced the call of Parasaurolophus, but he talked about his progress thus far at a virtual meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Lin was inspired in part by the dinosaur sounds featured in the Jurassic Park film franchise, which were a combination of sounds from other animals like baby whales and crocodiles. “I’ve been fascinated by giant animals ever since I was a kid. I’d spend hours reading books, watching movies, and imagining what it would be like if dinosaurs were still around today,” he said during a press briefing. “It wasn’t until college that I realized the sounds we hear in movies and shows—while mesmerizing—are completely fabricated using sounds from modern animals. That’s when I decided to dive deeper and explore what dinosaurs might have actually sounded like.”

A skull and partial skeleton of Parasaurolophus were first discovered in 1920 along the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada, and another partial skull was discovered the following year in New Mexico. There are now three known species of Parasaurolophus; the name means "near crested lizard." While no complete skeleton has yet been found, paleontologists have concluded that the adult dinosaur likely stood about 16 feet tall and weighed between 6,000 to 8,000 pounds. Parasaurolophus was an herbivore that could walk on all four legs while foraging for food but may have run on two legs.

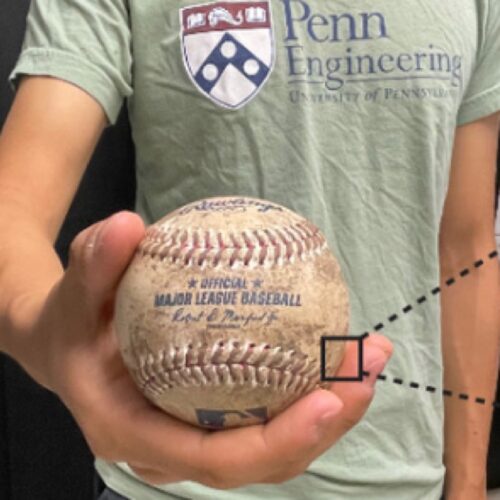

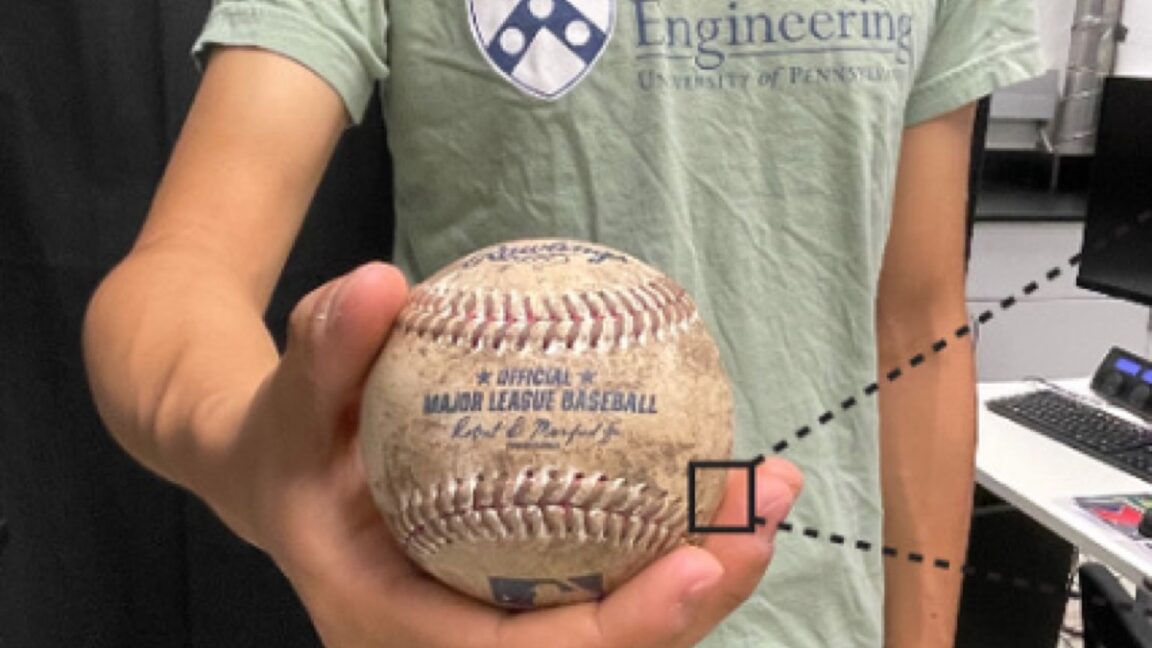

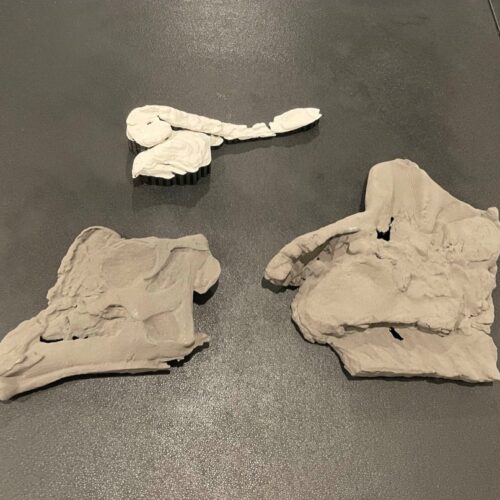

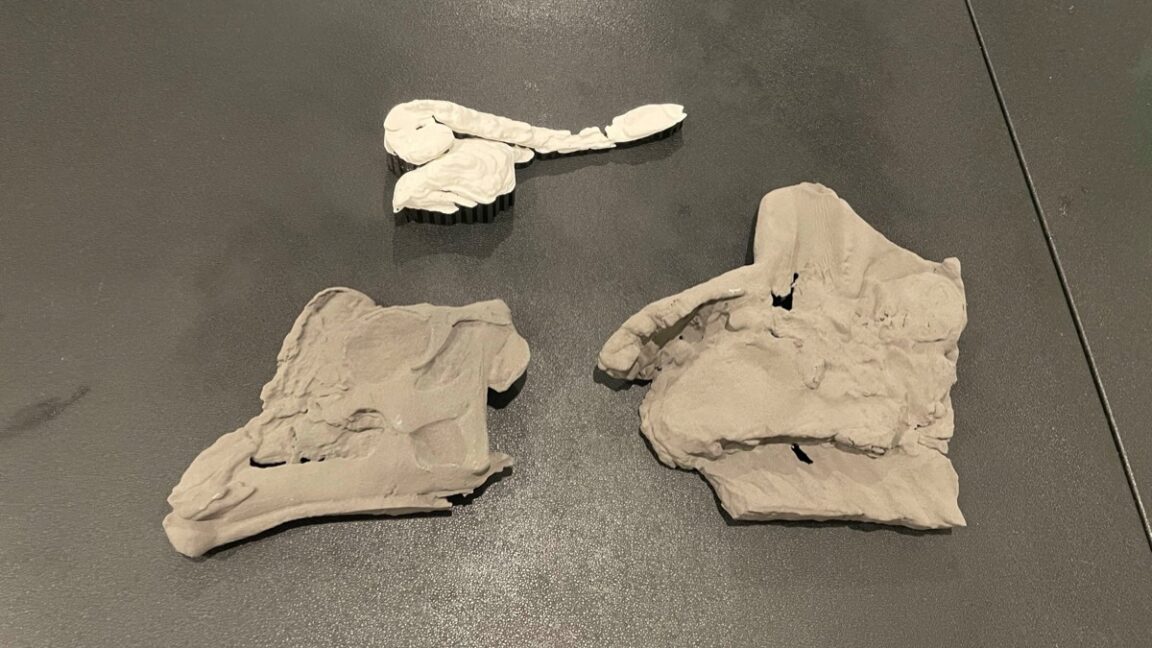

© Hongjun Lin