Trump Withheld Disaster Aid in the Past. His Old Subordinates Say He’ll Do It Again.

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Donald Trump deliberately withheld disaster aid to states he deemed politically hostile to him as president and will do so again unimpeded if he returns to the White House, several former Trump administration officials have warned.

As Hurricane Helene and then Hurricane Milton ravaged the southeastern US over the past two weeks, Trump has sought to pin blame upon Joe Biden’s administration for a ponderous response to the disasters, even suggesting that this was deliberate, due to the number of Republican voters affected by the storms.

But former Trump administration officials have said the former president, when in office, initially refused to release federal disaster aid for wildfires in California in 2018, withheld wildfire assistance for Washington state in 2020, and severely restricted emergency relief to Puerto Rico in the wake of the devastating Hurricane Maria in 2017 because he felt these places were not sufficiently supportive of him.

“Trump absolutely didn’t want to give aid to California or Puerto Rico purely for partisan politics—because they didn’t vote for him.”

The revelations, first reported upon by E&E News, have raised major doubts over what Trump’s response to disasters would be should he win next month’s presidential election. The former president has already been criticized for his role in spreading misinformation about Helene and Milton that has allegedly slowed the disaster response and even led to online death threats against Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) staff and meteorologists.

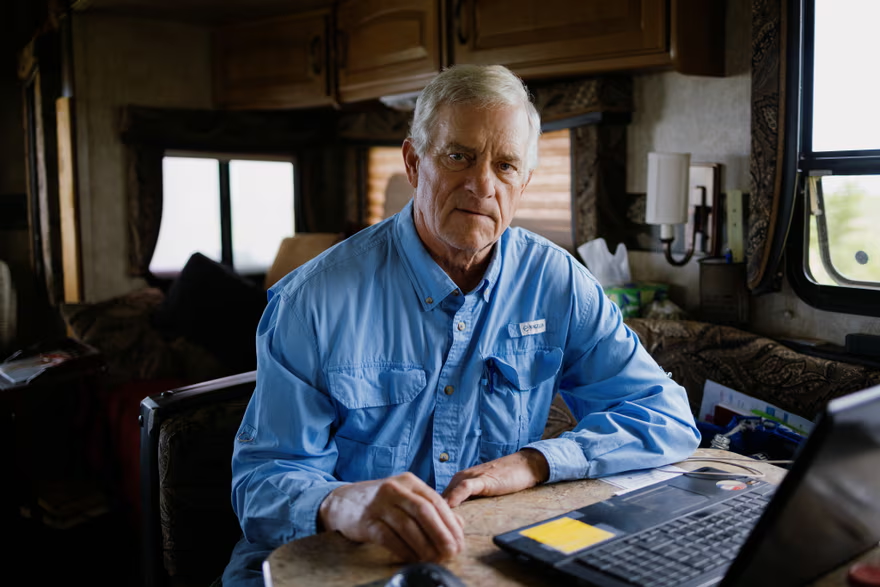

“Trump absolutely didn’t want to give aid to California or Puerto Rico purely for partisan politics—because they didn’t vote for him,” said Kevin Carroll, former senior counselor to Homeland Security secretary John Kelly during Trump’s term. Carroll said Kelly, later the president’s chief of staff, had to “twist Trump’s arm” to get him to release the federal funding via FEMA to these badly hit areas.

“It was clear that Trump was entirely self-interested and vengeful towards those he perceived didn’t vote for him,” Carroll told the Guardian. “He even wanted to pull the Navy out of Hawaii because they didn’t vote for him. We were appalled—these are American civilians the government is meant to provide for. The idea of withholding aid is antithetical to everything you want from in a leader.”

The effort to overcome Trump’s reluctance to provide aid for California succeeded only after the then-president was provided voting data showing that Orange county, heavily damaged by the wildfires, has large numbers of Republican voters, according to Olivia Troye, who was a Homeland Security adviser to the Trump White House.

“We had to sit around and brainstorm a way where he would agree to this because he looked at everything through a political lens,” Troye told the Guardian. “There were instances where disaster declarations would sit on his desk for days, we’d get phone calls all the time on how to speed things up, sometimes we had to get [Vice-President] Mike Pence to weigh in.

“It was shocking and appalling to us to see a president of the United States behaving in this way. Basically if it doesn’t benefit him, he’s not interested. We saw this in the Covid pandemic too, when it was red states versus blue states, and it’s still evident in his demeanor now, where he’s politicizing disaster response. It’s dangerous and reckless.”

“Most human beings would feel guilt in punishing people in pain whose homes are in ashes or are under 8 feet of water. It’s a window into the darkness of his soul, frankly.”

One of the most “egregious” delays, Troye said, came after Hurricane Maria smashed into Puerto Rico, causing widespread damage and nearly 3,000 deaths. In the wake of the disaster, Trump claimed the death toll had been inflated “to make me look as bad as possible,” called the mayor of San Juan “crazed and incompetent,” and halted billions of dollars of federal support for the island.

Ultimately, FEMA covered debris cleanup in Puerto Rico, and Trump visited the US territory, throwing paper towels to hurricane survivors. But not all recovery costs for the island were paid for by the federal government, with an independent inspector general report finding that FEMA mismanaged the distribution of aid following Maria.

This came just months before Trump agreed to pay 100 percent of Florida’s costs after the state was hit by Hurricane Michael. “They love me in the Panhandle,” Trump said, according to an autobiography written by Ron DeSantis, Florida’s Republican governor. “I must have won 90 percent of the vote out there. Huge crowds. What do they need?”

While officials around Trump were able to persuade him to relent somewhat in these instances, the former president held firm in refusing to provide disaster relief to Washington after wildfires ravaged the east of the state, largely destroying the communities of Malden and Pine City, in 2020.

For months, Trump denied Washington’s request for federal help due to his dislike of Jay Inslee, the state’s Democratic governor and a prominent critic, according to an aide of Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a Republican congresswoman whose district was scorched by wildfires.

McMorris Rodgers wrote to Trump to side with him in his dispute with Inslee while pleading with the president to release the funding. “Despite our governor’s bad faith personal vendetta against your administration, people in my district need support, and I implore you to move forward in providing it to those who have been impacted by devastating wildfires in our region,” McMorris Rodgers wrote.

Trump, however, did not agree to provide the help, which was only given once Joe Biden came into office. “Trump consciously and maliciously withheld assistance in a fit of juvenile pique because my state had the effrontery to question his policies,” Inslee told the Guardian.

“What’s so stunning is that Trump enjoys his authoritarian instincts in refusing to help people. Most human beings would feel guilt in punishing people in pain whose homes are in ashes or are under 8 feet of water. It’s a window into the darkness of his soul, frankly. We’ve seen with North Carolina again that he will use natural disasters for his own purposes and his fragile ego. He’s a clear and present danger.”

Carroll and Troye, former Trump administration officials, predicted there would be fewer constraints on Trump withholding disaster aid should he win another term in the White House. Several Trump allies, including those who wrote the Project 2025 conservative manifesto, have called for the Republican nominee to root out dissenters and install obedient political apparatchiks within the federal government to help enact his wishes.

“Next time you won’t have the integrity of Mike Pence: You’ll have JD Vance who will do whatever Trump wants,” said Troye, who is a Republican but has endorsed Kamala Harris for president. “It’s concerning to think about a future Trump administration with just loyalists in these positions around him in these sort of moments that should be non-partisan.

“I hope voters are paying close attention to contrast between the responsible leadership shown by Biden and Harris and the dangerous demeanor of Donald Trump.”

Just last month, Trump signaled that his dealmaking over disaster aid would not change if he were president again, warning that he would block assistance to California unless the state’s governor, Gavin Newsom, agreed to deliver more water to farmers. “Gavin Newscum is going to sign those papers,” Trump said from his golf course in California. “If he doesn’t sign those papers, we won’t give him money to put out all his fires, and if we don’t give him the money to put out his fires, he’s got problems.”

Karoline Leavitt, national press secretary of the Trump campaign, did not answer questions regarding the allegations made by Carroll and Troye, and instead referenced efforts by Trump to improve forest wildfire management and repeated debunked claims that disaster relief money has been diverted by FEMA to migrants.

“President Trump visited Georgia twice in one week to tour destruction from Hurricane Helene and has encouraged his supporters to donate more than $6 million for relief efforts on the ground,” she said, and then repeated a lie: “Kamala Harris stole $1 billion from FEMA to pay for illegal migrant housing and now there’s nothing left for struggling American citizens. President Trump is leading during this tragic moment while, once again, Kamala leaves Americans behind.”