NASA will proceed with final preps to launch Europa Clipper next month

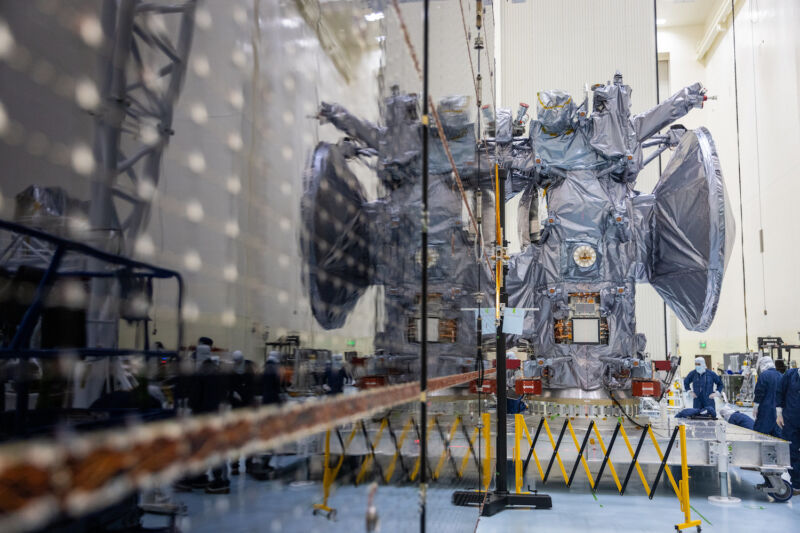

Enlarge / The main body of NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft is reflected in one of the mission's deployable solar array wings during testing at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. (credit: NASA/Frank Michaux)

For a while earlier this summer, it looked like NASA's flagship mission to study Jupiter's icy moon Europa might miss its launch window this year.

In May, engineers raised concerns that transistors installed throughout the spacecraft might be susceptible to damage from radiation, an omnipresent threat for any probe whipping its way around Jupiter. The transistors are embedded in the spacecraft's circuitry and are responsible for approximately 200 unique applications, many of which are critical to keeping the mission operating as it orbits Jupiter and repeatedly zooms by Europa, interrogating the frozen moon with nine science instruments.

The transistors on the Europa Clipper spacecraft are already installed, and removing them for inspections or replacement would delay the mission's launch until late next year. Europa Clipper has a 21-day launch window beginning October 10 to begin its journey into the outer solar system.