US Squandering Billions on Unproven Climate Solutions, Critics Say

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A handful of wealthy polluting countries led by the US are spending billions of dollars of public money on unproven climate solutions technologies that risk further delaying the transition away from fossil fuels, new analysis suggests.

These governments have handed out almost $30 billion in subsidies for carbon capture and fossil hydrogen over the past 40 years, with hundreds of billions potentially up for grabs through new incentives, according to a new report by Oil Change International (OCI), a non-profit tracking the cost of fossil fuels.

To date, the European Union (EU) plus just four countries—the US, Norway, Canada and the Netherlands—account for 95 percent of the public handouts on carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen.

“It is instructive that industry itself invests very little in carbon capture. This whole enterprise is dependent on government handouts.”

The US has spent the most taxpayer money, some $12 billion in direct subsidies, according to OCI, with fossil fuel giants like Exxon hoping to secure billions more in future years.

The industry-preferred solutions could play a limited role in curtailing global heating, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and are being increasingly pushed by wealthy nations at the annual UN climate summit.

But CCS projects consistently fail, overspend or underperform, according to previous studies. CCS—and blue hydrogen projects—rely on fossil fuels and can lead to a myriad of environmental harms including a rise in greenhouse gases and air pollution.

“The United States and other governments have little to show for these massive investments in carbon capture—none of the demonstration projects have lived up to their initial hype,” said Robert Howarth, professor of ecology and environmental biology at Cornell University. “It is instructive that industry itself invests very little in carbon capture. This whole enterprise is dependent on government handouts.”

With time running out to curtail climate catastrophe, critics of CCS and hydrogen say public money should be focused on proven, less risky solutions such as plugging leaky oil wells, energy efficiency for buildings, transport electrification, and renewables that will speed up the green transition.

The subsidies are a “colossal waste of money,” according to Harjeet Singh, global engagement director for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative. “It is nothing short of a travesty that funds meant to combat climate change are instead bolstering the very industries driving it.”

The US and Canada have spent more than $4 billion to subsidize the capture of CO2 that is then used to extract hard to reach oil reserves, a process known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), according to the OCI report shared exclusively with the Guardian.

“The history of CCS is depressing…and no significant innovations have improved CCS’s prospects.”

However, proponents argue that more investment is needed in developing CCS and hydrogen technologies, so they can help achieve global climate goals agreed under the Paris accords. “They are all part of the toolset we need to reach net zero,” Astrid Bergmål, state secretary in Norway’s ministry of petroleum and energy, told the Guardian.

Norway has so far approved $6 billion in subsidies for CCS, an energy-intensive process powered by fossil gas—which the country is also expanding.

The new analysis is based on two OCI databases: one tracking public awards distributed to companies from 1984 to 2024 for carbon capture and fossil-based hydrogen research and development, as well as grants for pilot and commercial projects. The other tracks government policies announced since 2020 in the US, Canada, Australia, the EU and countries in Europe that support grants, loans, tax credits, below market insurance plans and other financial incentives.

“Governments are pouring billions of taxpayer dollars into technologies that have consistently failed to deliver on their promises…allowing fossil fuel companies to continue business,” said Lorne Stockman, research director at OCI.

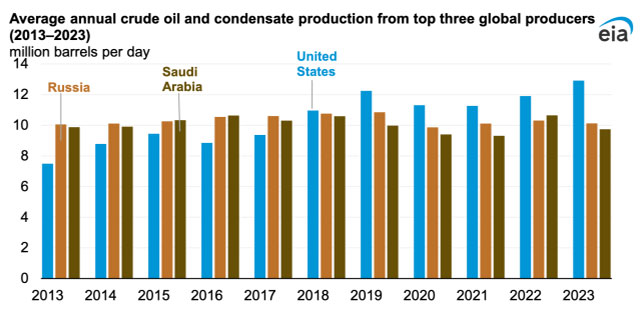

Subsidies from the US, the world’s biggest oil and gas producer where an estimated three-quarters of the CO2 currently captured is used for EOR, could top $100 billion, according to OCI analysis.

This is thanks to new policies from the Biden administration, particularly the landmark climate and infrastructure legislation—the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—which after intense industry lobbying expanded tax benefits for both CCS and hydrogen with few checks and balances.

Yet, experts warn that CCS technology is challenging and unlikely to deliver. “The history of CCS is depressing…and no significant innovations have improved CCS’s prospects,” said Charles Harvey, professor of environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who co-founded the first private CCS startup 15 years ago.

“Nonetheless, we are again wasting money on CCS that could be used instead to effectively cut emissions, distracting ourselves from the necessity of moving away from fossil fuels, and perpetuating a polluting industry whose local harms often fall on minority and economically disadvantaged communities.”

“I don’t think we should be directly subsidizing CCS ever…but we should directly subsidize clean things that are useful to people.”

Hydrogen, which is currently mostly used for refining oil, fertilizers, and processing metals and foods, could be green if companies chose to use water—not gas or coal—as the raw material, and power the process with renewables not fossil fuel. Yet globally, governments have spent $4.2 billion on projects that aim to produce blue hydrogen from fossil fuels using CCS.

The industry claims to have the technology to capture 90 percent to 95 percent of CO2, but in reality, it’s closer to 12 percent when every stage of the energy-intensive process is evaluated, according to peer-reviewed research by scientists at Cornell University. “The greenhouse gas footprint for this hydrogen is actually greater than if we were to simply burn natural gas for the energy,” said Howarth, a co-author of the groundbreaking study.

Canada is the second largest funder of blue hydrogen after the US with $1.2 billion spent to date, mostly at an oil refinery in Alberta where hydrogen is used for upgrading dirty tar sands crude. The net CO2 capture rate from the plant is less than 70 percent.

The Canadian and US government’s did not respond to requests to comment.

Globally, governments hand over between $500 billion and $1 trillion in direct fossil fuel subsidies annually, though in 2022 the true figure was closer to $7 trillion—when the climate, environmental and health costs were taken into account, according to the IMF. But more than $1 trillion is now also spent supporting clean energy, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) trackers, so the amount allocated to CCS and hydrogen is relatively small.

Still, after the hottest year ever recorded—and as island nations and other developing countries face an existential threat from sea level rise, desertification, drought, extreme heat, wildfires and floods—only $700 million was pledged by governments to the new loss and damage fund at Cop28—far short of the estimated $400 billion needed annually. The financial shortfall for climate adaptation runs into hundreds of billions—and is rising.

“Companies are designed to make profits, they only consider what is priced, so subsidies should come with conditions.”

Singh, director at the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, said: “While investing billions in technologies that further entrench fossil fuel use, developed countries simultaneously neglect their moral and financial responsibilities to fund crucial efforts in vulnerable communities…that’s the grim irony.”

While the decades-long reputation of CCS has largely been one of “underperformance” and “unmet expectations”, according to the IEA in 2023, many experts agree that it could play a role in reducing emissions in polluting industries such as cement, steel and chemicals.

But according to Chris Bataille, an IPCC expert on decarbonizing heavy industry, subsidies must come with conditions and target products, not processes, in order to achieve a just and economically sound green transition.

“I don’t think we should be directly subsidizing CCS ever…but we should directly subsidize clean things that are useful to people. Staggered subsidies for clean iron which is key to making steel, clean ammonia which is key for fertilizers and clean clinker for cement, would channel the market—which is the whole idea of government regulation.

“Companies are designed to make profits, they only consider what is priced, so subsidies should come with conditions, including mandatory net-zero transformation plans,” added Batallie, who is also adjunct research fellow at the Columbia University center for global energy policy.

At Cop28 in Dubai, the Netherlands launched a fossil fuel subsidy phase-out coalition amid growing public pressure to cut its financial support for oil and gas, which is currently estimated to be at least $43 billion a year.

The government has approved $2.6 billion for subsidies requested in 2020, with the vast majority allocated to the Porthos project—that will incentivize some oil majors and chemical companies at the Port of Rotterdam to store captured CO2 in an empty North Sea offshore gas field. (The figure doesn’t include subsidies approved in 2022 or requested in 2023.)

A spokesperson from the Dutch climate ministry said that the final amount paid out was expected to be substantially lower as it depends on the market price of carbon and project costs, and that these fossil fuel-powered technologies were key to the country’s green transition.

“This money should be used to get away from fossil fuels and making industrial processes green, rather than these false solutions.”

“In the Netherlands, safeguards have been built in for subsidies for CCS, so that these do not come at the cost of alternative, clean energy technologies. Dutch policy aims at minimizing the future role of fossil fuels in the energy system and has set conditions and a time horizon for fossil CCS support.”

Climate advocates say the phase-out is too slow.

“This money should be used to get away from fossil fuels and making industrial processes green, rather than these false solutions that are a cash cow for industry—in part because governments take over the risks from market fluctuations in the price of carbon,” said Maarten de Zeeuw, a climate and energy campaigner at Greenpeace Netherlands.

Norway’s first full-scale heavily subsidized CCS project was attached to the Mongstad oil refinery and described in 2007 by then prime minister, Jens Stoltenberg, as the country’s “moon landing.” The project failed, in part due to rising costs, though it did spawn a CCS test facility the government said is “instrumental in technology development.”

The country’s current flagship CCS project, the Longship, involves capturing CO2 from waste incineration and cement production that will be shipped and stored offshore. Costs here have also been rising—though, according to state secretary Bergmål, rising inflation and supply chain instabilities are also affecting other climate technologies.

OCI claims that Norway is expanding CCS to justify more oil and gas expansion for use producing blue hydrogen for export to Europe—where it is enjoying renewed interest despite evidence that its viability as an alternative fuel will be limited.

Bergmål said: “Managing CO2 from hard-to-abate industries has nothing to do with prolonged fossil fuel extraction. On the contrary, it is an urgently needed climate mitigation measure. One of the key goals of Longship is to provide learning and reduce costs for future projects…What matters is to produce enough volumes of hydrogen, with low to zero emissions, and at the lowest possible cost.”