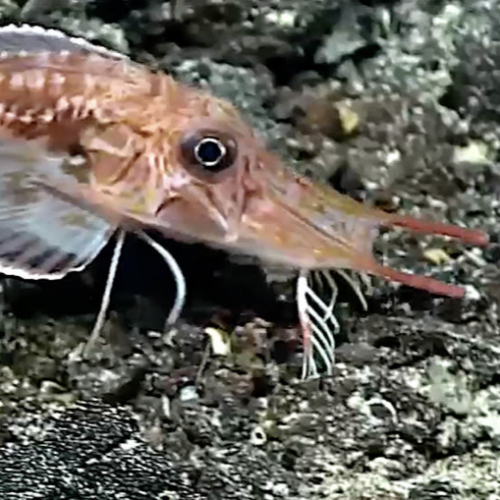

Manta rays inspire faster swimming robots and better water filters

Manta rays are elegantly shaped. They swim by flapping their fins like enormous wings, and their gills filter for plankton with the utmost precision. These creatures have now inspired human innovations that take soft robots and water filters to the next level.

With fins that borrow their shape and motion from mantas, a soft robot created by a team of researchers at North Carolina State University and the University of Virginia improves on a previous model by reaching speeds of 6.8 body lengths per second, nearly double what its predecessor was capable of. This makes it the fastest soft robot so far. It is also more energy-efficient than its previous iteration and can swim not just on the surface, but upward and downward, just like an actual manta ray.

Another research team at MIT used the gills of these creatures, which filter for plankton, to improve commercial water filtration systems. Their gill openings are also the perfect size to help them breathe while they feed, absorbing oxygen from water on its way out. The rays’ balance of feeding and breathing helped the researchers figure out a filter structure that more precisely controls inflow and outflow.

© MLADEN ANTONOV/AFP via Getty Images