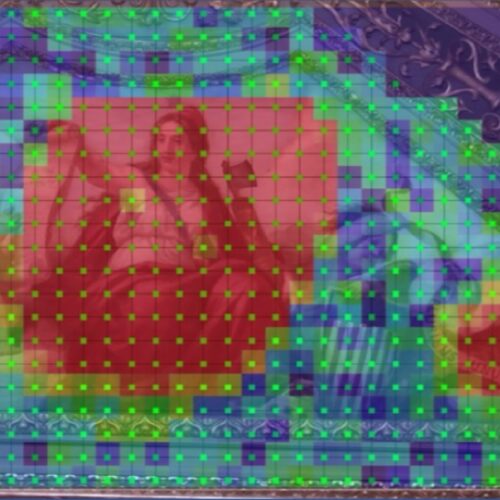

Study: Yes, tapping on frescoes can reveal defects

The US Capitol building in Washington, DC, is adorned with multiple lavish murals created in the 19th century by Italian artist Constantino Brumidi. These include panels in the Senate first-floor corridors, Room H-144, and the rotunda. The crowning glory is The Apotheosis of Washington on the dome of the rotunda, 180 feet above the floor.

Brumidi worked in various mediums, including frescoes. Among the issues facing conservators charged with maintaining the Capitol building frescoes is delamination. Artists apply dry pigments to wet plaster to create a fresco, and a good fresco can last for centuries. Over time, though, the decorative plaster layers can separate from the underlying masonry, introducing air gaps. Knowing precisely where such delaminated areas are, and their exact shape, is crucial to conservation efforts, yet the damage might not be obvious to the naked eye.

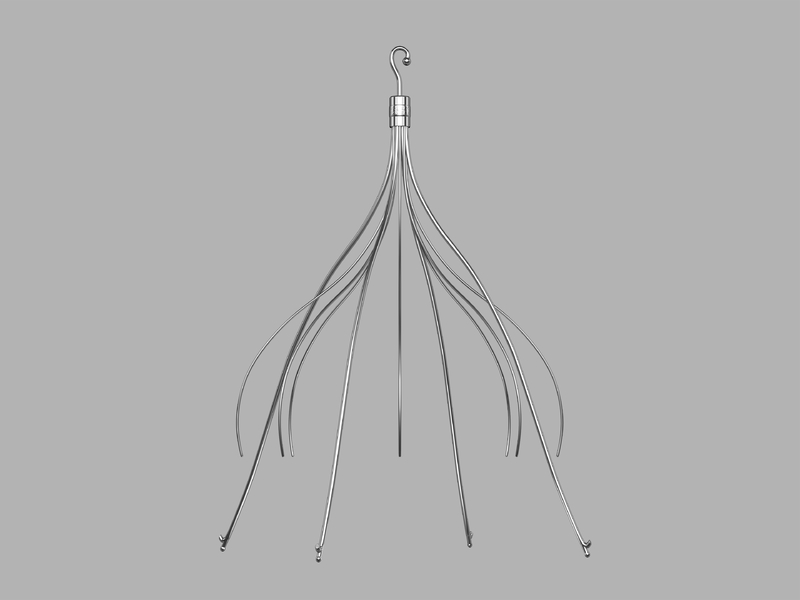

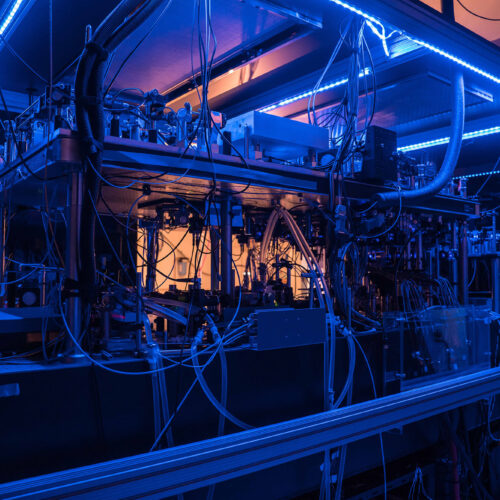

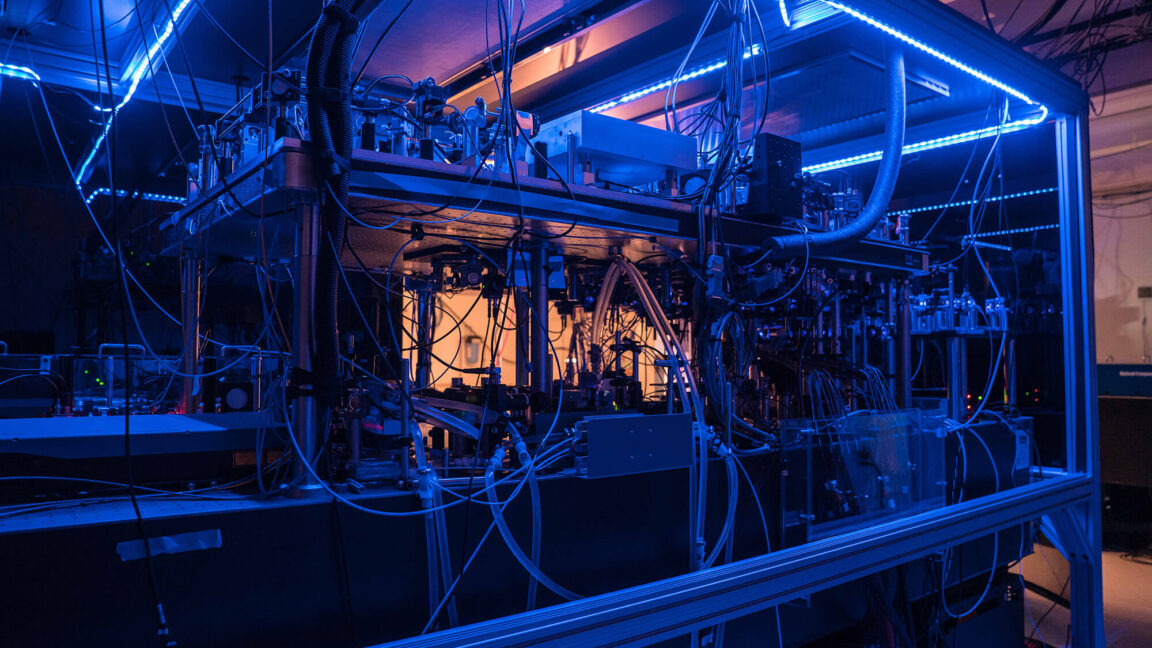

Acoustician Nicholas Gangemi is part of a research group led by Joseph Vignola at the Catholic University of America that has been using laser Doppler vibrometry to pinpoint delaminated areas of the Capitol building frescoes. It's a non-invasive method that zaps the frescoes with sound waves and measures the vibrational signatures that reflect back to learn about the structural conditions. This in turn enables conservators to make very precise repairs to preserve the frescoes for future generations.

© Nick Gangemi